- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"This is nature writing at its best." —E.O. Wilson

"Eloquent treatise...Landis's book is as much call to action as paean to mesmerizing molluscs." —Nature

"Rich, accurate, and moving." —New Scientist

"A lyrical love letter to the imperiled freshwater mussel." —Science

Abbie Gascho Landis first fell for freshwater mussels while submerged in an Alabama creek, her pregnant belly squeezed into a wetsuit. After an hour of fruitless scanning, a mussel materialized from the rocks—a little spectaclecase, herself pregnant, filtering the river water through a delicate body while her gills bulged with offspring. In that moment of connection, Landis became a mussel groupie, obsessed with learning more about the creatures' hidden lives. She isn't the only fanatic; the shy mollusks, so vital to the health of rivers around the world, have a way of inspiring unusual devotion.

In Immersion, Landis brings readers to a hotbed of mussel diversity, the American Southeast, to seek mussels where they eat, procreate, and, too often, perish. Accompanied often by her husband, a mussel scientist, and her young children, she learned to see mussels on the creekbed, to tell a spectaclecase from a pigtoe, and to worry what vanishing mussels—70 percent of North American species are imperiled—will mean for humans and wildlife alike. In Immersion, Landis shares this journey, traveling from perilous river surveys to dry streambeds and into laboratories where endangered mussels are raised one precious life at a time.

Mussels have much to teach us about the health of our watersheds if we step into the creek and take a closer look at their lives. In the tradition of writers like Terry Tempest Williams and Sy Montgomery, Landis gracefully chronicles these untold stories with a veterinarian's careful eye and the curiosity of a naturalist. In turns joyful and sobering, Immersion is an invitation to see rivers from a mussel's perspective, a celebration of the wild lives visible to those who learn to search.

"Eloquent treatise...Landis's book is as much call to action as paean to mesmerizing molluscs." —Nature

"Rich, accurate, and moving." —New Scientist

"A lyrical love letter to the imperiled freshwater mussel." —Science

Abbie Gascho Landis first fell for freshwater mussels while submerged in an Alabama creek, her pregnant belly squeezed into a wetsuit. After an hour of fruitless scanning, a mussel materialized from the rocks—a little spectaclecase, herself pregnant, filtering the river water through a delicate body while her gills bulged with offspring. In that moment of connection, Landis became a mussel groupie, obsessed with learning more about the creatures' hidden lives. She isn't the only fanatic; the shy mollusks, so vital to the health of rivers around the world, have a way of inspiring unusual devotion.

In Immersion, Landis brings readers to a hotbed of mussel diversity, the American Southeast, to seek mussels where they eat, procreate, and, too often, perish. Accompanied often by her husband, a mussel scientist, and her young children, she learned to see mussels on the creekbed, to tell a spectaclecase from a pigtoe, and to worry what vanishing mussels—70 percent of North American species are imperiled—will mean for humans and wildlife alike. In Immersion, Landis shares this journey, traveling from perilous river surveys to dry streambeds and into laboratories where endangered mussels are raised one precious life at a time.

Mussels have much to teach us about the health of our watersheds if we step into the creek and take a closer look at their lives. In the tradition of writers like Terry Tempest Williams and Sy Montgomery, Landis gracefully chronicles these untold stories with a veterinarian's careful eye and the curiosity of a naturalist. In turns joyful and sobering, Immersion is an invitation to see rivers from a mussel's perspective, a celebration of the wild lives visible to those who learn to search.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immersion by Abbie Gascho Landis in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781610918084Subtopic

Natural HistoryChapter 1

Breaking Water

May what I do flow from me like a river,

no forcing and no holding back,

the way it is with children.

Rainer Maria Rilke

On a March day in 2009, nine years after Chewacla Creek dried up, I stood in the roadside weeds near a county road bridge in Alabama. The creek—the city of Auburn’s water supply—was flowing again, thanks to legal protection. I was wiggling first my legs, then my arms, into a borrowed wet suit. I left it unzipped while I bent over, one hand on the truck’s tailgate for balance. My other hand reached to shoehorn my sneakers over neoprene booties. I straightened, returning my attention to the zipper. It gaped like an open shell, displaying my pregnant belly, almost four months round. With effort, I zipped up the two halves, encasing myself. My first child would dangle below me while I snorkeled—something I’d never done before.

I had joined this Auburn University field crew on a whim, based on a last-minute invitation. Stopping by a sporting goods store on the way, I had purchased a snorkel mask. The kid-sized snorkels fit my face better than adult ones, so I now carried a cartoonish fluorescent green snorkel, in contrast to everyone else’s blue or black professional-looking gear. One these biologists was my husband, Andrew. He watched his whole family squeeze into my wet suit, then pointed us toward the creek.

We thrashed along, dropping down a steep bank, departing the road where it headed over the bridge. I picked my footing and eyeballed poison ivy, glad for the neoprene suit. Stepping into the creek, we spread out and moved upstream, away from the bridge where we had parked the truck. I sank to my knees, letting cool water flow over my thighs. It was shallower than a bathtub. When I eased forward onto my hands, the water didn’t even cover my back. Biting the snorkel mouthpiece, I submerged my head through a layer of crisp-edged leaves and into another world.

A fish darted close—its eyes, its finely lined fins. Its gills clapped against its head as if it was slowly applauding my green-rimmed face. The creek filled my wet suit and filled my ears, dimming other sounds, gurgling through my head like a pitcher pouring into an endless glass. I reveled in the bright underwater world, delighting at each colorful darter slipping in and out of view. Sediment stayed on the creekbed, leaving the water clear until my fingers swept the rocks, raising a cloud. I grazed my belly upstream into better visibility, moving slowly to the rhythm of my breath whooshing up and down my snorkel.

Months later, when I learned the word for this creekbed world—benthos—I would remember each curled snail and crayfish scooting backward. The river bottom, the depths, the benthic bottom dwellers. I met the benthos face to face.

Then I lifted my head and realized I had fallen well behind the others. I slurped myself to a standing position and waded toward the bank. They had told me that the creek’s edges often held many hidden freshwater mussels. Finding those mussels was our purpose for snorkeling Chewacla Creek in March.

Look for two small openings, they told me. Like two short tubes often sticking up just a bit from the mud. “Once you get your search image, it’s easy,” Professor Jim Stoeckel, a compact man who rarely stood still, assured me from across the creek. “You’ll really start seeing mussels.”

After about an hour, the extent of Stoeckel’s optimism became apparent. I had plucked and flipped and groped at least fifty rocks, leaves, twigs, and lumps in the mud. I’d never seen a mussel in the wild. My search image, which resembled two short drinking straws poking out of the mud, wavered like a mirage.

“It’s really hard to describe what to look for,” Andrew told me later. “I look for what is not mud and rocks. Something that has a particular shape. Something that’s more perfect than everything surrounding it.”

I refocused, remembering photos I’d seen, and tried to imagine our quarry. These are not the coal-black ocean mollusks clinging like butterflies to rocks or jumbled on plates under decadent sauces. Neither are they the notorious zebra mussels, Dreissena polymorpha, invasive species plaguing rivers and lakes north of here. The family Unionidae, native freshwater mussels, lives in creeks and rivers and includes almost three hundred species in North America. Nearly 70 percent of them are imperiled.

These freshwater mussels live mostly buried. Their shell edges are parted like a surprised gasp, exposing two apertures. One intakes and the other releases water, which is how mussels eat, breathe, and even gather sperm to meet their eggs. Those apertures actually look like Georgia O’Keefe paintings—flowers, female anatomy—elegant ovals decorated with variously shaped and colored papillae. Apertures, papillae, curve of a shell. This is our search image.

Although I did not see her, a mussel was there, near my feet. Sometimes, sidling along with one meaty foot, this mussel would leave a trail, but now she nestled into sandy clay. Above this mussel, water flowed. Water flowed quickly, riffling and tugging her. Sometimes water barely flowed at all, pooling in the dry summer. Sometimes it flowed like cappuccino, dense with particulate, challenging the mussel’s filtering gills. Other times it flowed clear from bottom to surface, like today.

We stood in our wet suits, leaning toward the creekbank. Andrew pointed; I struggled to see what he described. Between my protruding abdomen and taut wet suit, I couldn’t bend my waist, so I bent my knees and tipped forward.

“She’s displaying,” he told me. He waited while I stared.

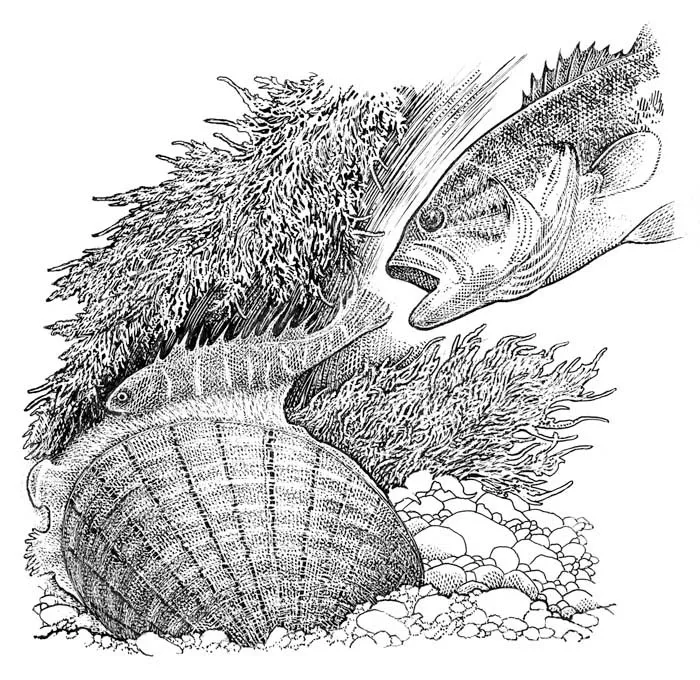

Then the mussel seemed to materialize, differentiating from the leaves and rocks. Before my eyes, the creek bottom gained a dimension as I perceived its complexity. A little spectaclecase, Villosa lienosa, was doing the work of a freshwater mussel—filtering. She was also doing the work of many females this time of year—displaying. Her gills bulged with offspring that she’d brooded for months. Now the time had come. Above those offspring waved her mantle lure, decorated with multiple tentacles that looked like a clump of small black worms. The bait.

Ripe with progeny, the female mussel must attract a fish to deliver her babies into the world. Striking the bait, a fish will release thousands of these larval mussels, which will hitch a ride on the fish’s gills, transforming into independent juveniles and then letting go and sinking into their new creekbed lives. I was impressed. Delivering offspring into the world clearly demanded heroic efforts.

I recognized this turning inside out for the next generation. This mussel and I were similarly vulnerable, preparing to empty our bodies into the future. Watching a wild mussel display her lure opened a door in my mind, like my first kiss. I became a freshwater mussel groupie. I fawned over their photographs, mussels ranging in size from thumbnail to dinner plate, building glassy or ridged or pimpled shells that are brown or black or yellow, with or without dark stripes fanning across them, and always paved inside with pearl—white, pink, deep violet. I stalked them from a distance, writing their names in my notebooks: fatmucket, pistolgrip, heelsplitter, shinyrayed pocketbook, spectaclecase, pigtoe, snuffbox. I pored over their bios. Posters of mussels hung in our bedroom.

Largemouth bass striking a finelined pocketbook lure

Freshwater mussels are old. As a group, they have persisted and adapted across, some scientists estimate, around five hundred million years. Mussels share a family-tree branch with other mollusks. Their phylum, Mollusca, includes snails and slugs, squids and octopus, and clams and scallops, to name a few. Their class, Bivalvia, notably features multitasking gills. These versatile organs help with respiration, excretion, and reproduction. Breathing, defecating, and making babies all coincide in one efficient organ.

Mussels ingest particles suspended in water drawn across their gills, which sort particles as edible or inedible. The water flowing in Alabama’s creeks and rivers, the water sitting in catfish ponds and reservoirs, the water gushing from my own faucet, has probably passed through the interiors of freshwater mussels. As they filter feed, mussels also ingest contaminants into their sensitive bodies. Mussels burrow at the intersection of water and earth, so they suffer with disruptions to both creek channel and water. Their life cycle requires fish to host their parasitic larvae, linking mussels to vulnerable fish diversity. In these ways, mussels embody the whole river.

These mussels have been called naiads, after Greek mythology’s freshwater nymphs—beautiful and powerful, ancient and ageless, epic and endemic—each linked inextricably to a particular stream or river. Naiads give life and draw life from the water. If a river is destroyed, so is its naiad. When a waterway changes, mussels are the first to know. They may simply die, or they may live but be unable to lure fish to their offspring. If their reproduction is thwarted for too long, they go extinct. Aquatic ecologists who study freshwater mussels have been sounding alarms for decades. Threatened, endangered, and extinct wail like sirens across lists of freshwater mussels. As eminent biologist and Alabama native E. O. Wilson insists in his foreword to Freshwater Mussels of Alabama and the Mobile Basin, “Mussels are not dismissible, even by those who have little interest in the natural world.”

Mussels’ peril is our own. We need the same thing—plentiful clean water in healthy creeks and rivers. I think of mussels as I watch the kitchen spigot run. I heed their dwindlings and extinctions as a smoke detector piercing the night. Feel alarmed, they insist. Get up and look around. The house just might be on fire.

In the spring of 2000, while a dry spell crept steadily toward severe drought, Mike Gangloff crawled through Chewacla Creek finding handfuls of finelined pocketbook mussels. He’d hiked to the creek through woods that sang a high-pitched green, trilliums blooming in a harmony of white under the trees’ green melody. He’d slipped past eight-foot-high hurricane fencing meant to keep hikers from falling into abrupt sinkholes big enough to swallow a six-foot-tall, thick-shouldered graduate student or, as it would happen, an entire creek. As the drought deepened, Gangloff would watch this creek disappear, taking with it scores of mussels—most notably, the threatened finelined pocketbooks.

As a kid from Long Island, New York, Gangloff spent childhood family vacations upstate, filling buckets with frogs and salamanders and attempting to introduce them into swamps near his house, but he always idealized Alabama. Gangloff remembers looking at his Peterson field guides as a kid, fantasizing about the many species in the Southeast. He longed to catch an alligator snapping turtle in an Alabama swamp. Once he learned the region’s fish and other fauna, it became, for him, the place to be.

Gangloff met freshwater mussels while in Montana getting his master’s degree and then leapt at an opportunity to study mussels at Auburn University, in the epicenter of mussel biodiversity. Few biologists were researching mussels in Alabama, and an Auburn professor had received federal funding through the Endangered Species Act, specifically for studying mussel populations. Gangloff left Montana winter and arrived in relatively balmy Alabama in January 1999.

Gangloff’s actual dissertation project focused on mussels in the Coosa River system, a drainage separate from Chewacla Creek. But Chewacla was close to Auburn, so Gangloff could visit it to work on his methods and get to know mussel species without traveling. He wanted to fiddle with population survey techniques in stream sites with both lots of mussels and very few. In Chewacla Creek, those turned out to be the same sites. Gangloff’s sampling spots, mussel laden before the drought, would be mussel-poor one year later.

In May 2000, Gangloff and crew traipsed upstream beyond the Chewacla State Park boundary, past a spot called Pretty Hole, to one of their study sites. They knelt in gravel beds and rocky cobble—great mussel habitat. Belly down, they snorkeled, except where water was too shallow to submerge their heads. They found and identified ninety-three mussels of seven species. Of those ninety-three mussels, sixty-three were finelined pocketbook mussels. Finelined pocketbooks, Hamiota altilis, are oval-shaped, tawny- colored mussels the length of a crayon and have thin dark rays spreading from hinge to edge like a fan. Recognized as a threatened species by the US government, finelined pocketbook mussels—and their habitat—are protected by the Endangered Species Act. As Chewacla Creek levels fell, these mussels would rise to new infamy in Auburn, Alabama.

By that summer, about 80 percent of Chewacla Creek had disappeared. Long runs and riffles went completely dry. Water persisted only in pools,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Breaking Water

- Chapter 2: Rocks with Guts

- Chapter 3: The Lure of Mussels

- Chapter 4: Search Images

- Chapter 5: Mussel Memory

- Chapter 6: Life at River Bottom

- Chapter 7: The Dead River

- Chapter 8: When to Clam Up

- Chapter 9: Holding Water

- Chapter 10: Mussel Resuscitation

- Acknowledgments

- Selected Bibliography