- 193 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many medical professionals are now seeking to train in Cosmetic Practice, and there are many courses offering practical training and many texts offering detailed guides to the procedures; this text offers instead a helpful overview of the fundamentals involved and how they impact on practical skills, patient management, and potential complications. It constitutes the perfect guide to professional certification and beyond that to Cosmetic Practice.

*Presents the starter in aesthetic practice with the fundamentals of minimally invasive treatments. *Offers a reliable resource for any medical professional wishing to certify in this specialty.

*Combines material on both main treatment and on aesthetic patient management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fundamentals for Cosmetic Practice by Michael Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Medicina de familia y práctica general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

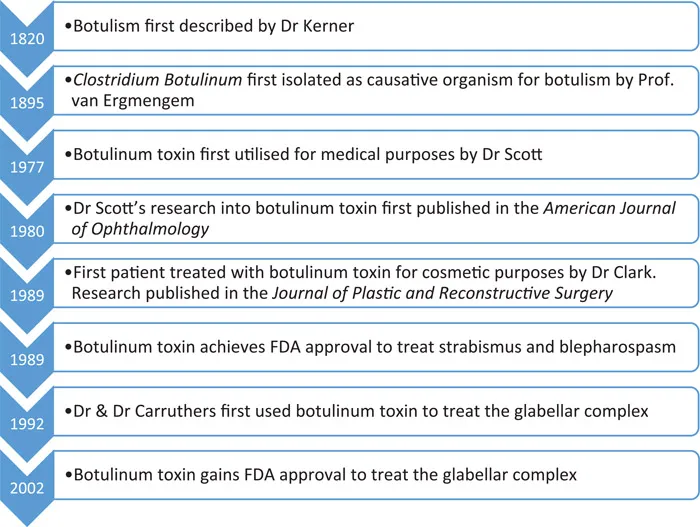

1 The history of botulinum toxin

DOI: 10.1201/9781003198840-1

In 1820, a German medical officer, Justinius Kerner, first described the effects of botulism after systematically observing the effects of the disease then known as “sausage poisoning”. He discovered through numerous experiments on both himself and animal models that botulinum toxin would interrupt somatic (conscious motor) and autonomic (unconscious) nerves without having any impact on the sensory or cognitive functions of the individual tested.

Seventy-five years later in 1895, Professor Émile van Ermengem identified Clostridium botulinum as the causative organism for the disease botulism after 34 funeral attendees were noted to develop symptoms of this disease after eating partially salted ham. Professor van Ermengem discovered that extracts from the ham served at the funeral induced botulism-like symptoms in laboratory animals, allowing the link to be made between this bacterium and disease.

The medical implications of botulinum toxin were first successfully utilised in the 1970s by Dr Alan Scott. His initial studies on primates revealed that injecting mere picograms of the toxin into the muscles around the eye caused long-lasting paralysis with no significant side effects. After securing a licence from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Dr Scott began to produce botulinum type A neurotoxin in a lab in San Francisco. He hypothesised it may work for strabismus, and subsequently proceeded to treat his first patient with this condition with Botulinum toxin in 1977 before publishing his results in the journal of the American Academy of Ophthalmology in 1980. He named the botulinum toxin he had synthesised Oculinum, or “eye-aligner”.

The cosmetic implications for botulinum toxin were identified in the late 1980s by Dr Richard Clark, who had a patient who had sustained paralysis of one of the nerves of their forehead following complications during a facelift. He was aware that the nerves may take up to two years to fully regenerate and therefore did not want to perform any further surgical interventions until this time had elapsed. Dr Clark was aware of the previous work by Dr Scott and others in using botulinum toxin in the treatment of strabismus and facial tics and supposed that it may also work in smoothing forehead wrinkles. After achieving FDA approval, Dr Clark successfully treated his patient in 1989 and published his results in the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. The work of Dr Clark was further developed by a husband-and-wife duo, Dr & Dr Carruthers, one a dermatologist and the other an ophthalmologist, who successfully used botulinum toxin to treat the glabellar complex, the primary muscle group of the face involved in frowning. Their research was first published in 1992.

After further extensive research, the FDA gave a licence for the use of botulinum toxin A to treat the glabellar complex, and its cosmetic use has continued to grow. At present, it is frequently used in cosmetics to treat forehead wrinkles, frown lines and “crow’s feet” around the eyes. See Figure 1.1.

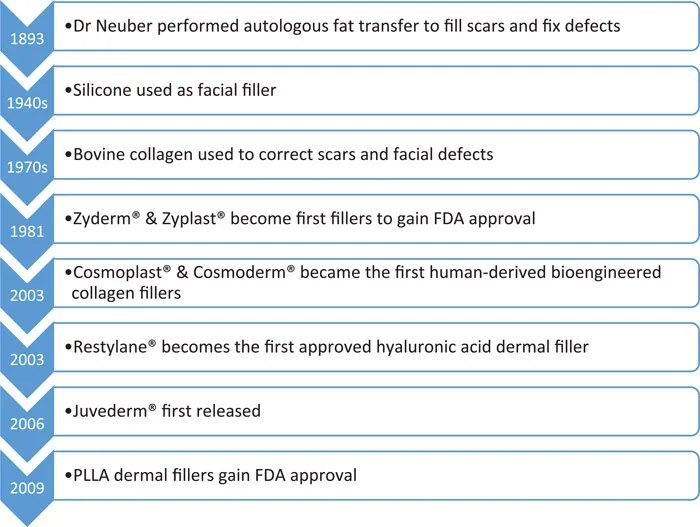

2 The history of dermal fillers

DOI: 10.1201/9781003198840-2

The success of botulinum toxin for treating fine lines and wrinkles in the upper face demanded a product of similar efficacy to treat age-related changes of the lower face. Consumer desire for office-based procedures with minimal downtime and side effects has driven innovation in the field of dermal fillers. For a product to be acceptable to both patient and physician, it needs to be safe, effective, convenient, and affordable. The side effects must be minimal, the pain must be tolerable, and the results need to be of a predictable duration, with straightforward storage, preparation and administration. At present, there are in excess of 35 companies producing dermal fillers worldwide, offering a range of choice to both practitioners and consumers. The myriad of dermal fillers available for purchase allows practitioners to select dermal fillers with the appropriate qualities to create their desired cosmetic outcomes.

The use of dermal fillers began in 1893, when a German physician, Dr Franz Neuber transplanted endogenous fat from the arms of patients to their faces to fill defects and reconstruct scars. The first exogenous cosmetic injectable was paraffin in the late 1800s; however, this was soon abandoned due to significant complications including embolisation, migration and granuloma formation. From the 1940s to the 1950s, silicone was used as a dermal filler agent; however, it was never approved by the FDA for facial augmentation. It was inevitably banned as an exogenous dermal filler in 1992 due to its side-effect profile, including silicone embolism syndrome and the formation of nodules and granulomata due to the host’s response to foreign bodies. Silicone embolism syndrome was arguably the most serious potential side effect of the use of this filler, presenting with shortness of breath, hypoxia, haemoptysis and proving fatal in up to one-quarter of patients affected.

Next, in the 1970s, came animal-based collagen derived from calfskin. Bovine collagen was used to correct acne and pockmarks, lipoatrophy in HIV and soft-tissue augmentation of the lower face. Zyderm® and Zyplast®, manufactured by Allergan, were produced by Stanford University and approved by the FDA in 1981, becoming the first injectable formally approved for soft-tissue augmentation. These were, on the whole, well tolerated, yet as the tissue is foreign to that of the host, skin testing for sensitivity had to be carried out pre-treatment to decrease the risk of hypersensitivity reactions. The need for skin testing and limited duration of action restricted the popularity of bovine collagen; however, it remained the only approved injectable filler for over 20 years until the development of the first human-derived bio-engineered collagen fillers in 2003: Cosmoplast® and Cosmoderm®. These agents had the advantage of not requiring skin testing as they are human-derived products and subsequently confer a very low risk of hypersensitivity reactions. More recently, autologous collagen filler has been used, harvested from the patient during elective surgery, for example Autologen®, developed by the Collagenesis corporation. These fillers also have a relatively short duration of action of approximately seven months, and when paired with the need for surgical procedures to obtain them, they have not garnered much popularity.

December 2003 signified the arrival of hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers, which have both a longer effective timespan and more tolerable side effect profile in comparison to collagen fillers. The first FDA approved HA filler was Restylane®, produced by Galderma. HA can be animal or non-animal derived and is a naturally occurring polysaccharide found throughout cutaneous tissues, making allergic reactions theoretically impossible. HA fillers can be used for cosmetic augmentation, filling of defects, and softening wrinkles. Their plumping effects are in no small part due to their hydrophilic properties, and they also may confer longer-term effects due to neocollagenesis. The next HA filler to be developed, Perlane®, was a more viscous form of Restylane and was approved for use by the FDA in 2007. Restylane® and Perlane® are non-animal derived HA fillers synthesised by cultures of the bacteria Streptococcus equii. Another commonly used HA dermal filler is Juvederm®, produced by Allergan and first released in September 2006.

The main limitation of HA fillers is their relatively short duration of action when compared with permanent fillers, which is discussed later. They do, however, have the advantage of being dissolvable by hyaluronidase if the effect is undesirable or should complications occur. The decision to add lidocaine to the product for local anaesthesia revolutionised patient comfort and the tolerability of dermal filler treatments. The first dermal filler to include lidocaine was created by Anika Therapeutics and named Elevess®. It is a non-animal-derived product and, at the time of writing, has the highest concentration of HA available in a commercial filler. More recent products such as Puragen® use double-cross-link technology reducing the rate of degradation and increasing their ability to add volume.

Formulations of non-permanent dermal filler which are not HA based include poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) and calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHa). PLLA was first licensed by the FDA in 2009 under the trade name Sculptra®. These fillers are broken down over an average of nine months to two years after administration; however, their cosmetic effects often last longer than this due to stimulation of neocollagenesis through activation of dermal fibroblasts. CaHa fillers are made up of microspheres which illicit minimal foreign body reaction, do not migrate within tissues and trigger neocollagenesis alongside their volume-enhancing effects. As it is a more viscous filler, CaHa is primarily designed for use in deeper soft tissues, such as the cheeks. See Figure 2.1.

3 Facial anatomy

DOI: 10.1201/9781003198840-3

Before treating a patient with botulinum toxin or dermal fillers, it is essential to understand exactly where you are inserting your needle and why you are aiming for that particular part of the face. As you progress through your training and develop your practice, you will find that more often than not, your anatomical knowledge is crucial for safely administering treatments and for working out how to treat your more complex patients. In this section, we cover the relevant musculoskeletal anatomy of the face, the nervous and arterial supply and venous and lymphatic drainage. Gaining an intimate knowledge of these complex anatomical structures will give you a solid foundation to treat your patients safely and effectively in the future.

FACIAL BONES

Before considering the soft tissues of the face, one must first gain an appreciation of the bones to which they are attached. The bones not only offer protection to the eyes and brain, but also give structural support to the muscles and vasculature of the face itself. The true facial skeleton is made of fourteen bones; however, we shall also include the frontal bone in our discussion of facial osteology for practical purposes – bringing our number of bones up to fifteen.

The bones of the face (Figure 3.1) include the following:

- Frontal bone, the bony part of the forehead

- Sphenoid bone, the lateral portion of which can be demonstrated inferio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements and Preface

- Chapter 1 The history of botulinum toxin

- Chapter 2 The history of dermal fillers

- Chapter 3 Facial anatomy

- Chapter 4 Anatomy, physiology, and histology of the skin

- Chapter 5 The science of ageing

- Chapter 6 Patient assessment

- Chapter 7 Communication skills

- Chapter 8 Introduction to botulinum toxin

- Chapter 9 Botulinum toxin practical skills

- Chapter 10 Botulinum toxin complications and management

- Chapter 11 Introduction to dermal fillers

- Chapter 12 Dermal fillers: practical skills

- Chapter 13 Dermal filler complications and management

- Bibliography

- Index