![]()

Part 1: Theoretical Underpinnings

![]()

1 A Brief but Comprehensive Overview of Self-Determination Theory

Johnmarshall Reeve

Two generations ago, Edward L. Deci completed his dissertation by asking how different types of extrinsic reinforcements (e.g. money, praise, threats of punishment) might affect intrinsic motivation (Deci, 1972a, 1972b). The basic finding was that task-related intrinsic motivation decreased after receiving an ‘if-then’ contingent reward (money), a threat of punishment for poor performance, or negative performance feedback. Through these studies, Deci (a) introduced selfdetermination theory’s first major phenomenon (i.e. intrinsic motivation; Deci, 1975); (b) created the first mini-theory to explain these findings (i.e. cognitive evaluation theory; Deci & Ryan, 1980); and (c) laid out a road map for how SDT would be built – namely, by resolving a specific and controversial research question, which was: ‘How do extrinsic rewards affect intrinsic motivation?’ The practical implications of this work were immediately obvious, so Deci also used SDT to (d) speak to issues of practical application.

Self-Determination Theory

Today, self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017) exists as an integrative macro-theory of human motivation and personality. SDT is an amalgamation of six mini-theories, each of which was created to resolve a separate research question. What unites these mini-theories into a single macro-theory is a set of three shared assumptions about the nature of human motivation and how social conditions affect it. SDT’s overarching goal is to use empirical methods to explain how social conditions sometimes enhance but other times undermine human flourishing.

Theoretical Assumptions

SDT is built on three key theoretical assumptions. The first assumption is that of intrinsic activity. SDT assumes that it is human nature to be inherently active. In education, the assumption is that every student-learner is naturally prone toward activity, engagement, learning, and personal growth. Proactive, agentic interaction with the environment is the natural state of motivation, while motivational passivity is a symptom of something gone awry. This first assumption highlights the importance of motivational constructs such as intrinsic motivation.

SDT’s second assumption is that of inherent tendencies toward growth. SDT is an organismic approach to human motivation. Organisms are always in active exchange with their environmental surroundings, and their flourishing depends on access to a nurturing environment. When environments provide the resources and opportunities to support organisms’ growth-oriented nature, organisms thrive and fulfil their inherent tendencies toward growth, differentiation and integration. When the surrounding environment fails to provide these resources and nutriments, organisms and organismic development suffer and flounder. This second assumption highlights the source of people’s inherent growth tendencies – the three psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness as essential nutriments.1

SDT’s third assumption is the person–environment dialectic. In a dialectic, each agent (person, environment) changes the other, and the relationship evolves either toward synthesis and mutual support or toward conflict and mutual antagonism. In an educational setting, the learner eagerly seeks out and proactively interacts with the educational environment – seeking resources, learning new information, discovering new and more effective ways to cope, internalizing more mature ways to think and behave, and trying to create a more motivationally supportive environment for oneself. In turn, the environment affords the learner with new and constructive ways of thinking and acting. If the learner finds these environmentally recommended and modelled ways of thinking and acting to be helpful, two benefits occur. First, the learner experiences need satisfaction, personal growth and well-being. Second, the learner willingly internalises these environmentally sourced motivations into the self-structure (e.g. acquired beliefs, values, goals, standards, ways of coping). SDT’s third assumption highlights the importance of agency, internalization, differentiation, integration and autonomous extrinsic motivation. It highlights that people have inherent sources of motivation and that further they have acquired (internalized) sources of motivation.

Originally, each assumption was adopted as a theoretical position, one that was assumed to be true but was not open to empirical testing. Since SDT’s early formulation, however, advances in technology and the emergence of new and sophisticated data analytic techniques have enabled hundreds of clever researchers from all around the globe to discover ways to put these theoretical assumptions to empirical test. For instance, the assumption of inherent sources of motivation (intrinsic motivation, psychological needs) has been affirmed by neuroscientific investigations of brain structure and functioning (Reeve & Lee, 2019). The assumption of environmental supports and thwarts that satisfy or frustrate psychological needs has been affirmed by ‘dualprocess theory’ research on ‘bright side’ and ‘dark side’ catalysts and functioning (Bartholomew et al., 2011). New and highly sophisticated statistical software programs (e.g. multilevel structural equation modeling analyses) allow global researchers to test for SDT’s predicted longitudinal, reciprocal causation and cross-cultural effects (Reeve et al., 2020).

The capacity to put SDT’s theoretical assumptions to empirical test has informed the debate about the theory’s validity and generalizability. Empirical evidence has overwhelmingly supported the theory. That said, almost all the controversies involving SDT occur not around its empirical evidence but, instead, with its theoretical assumptions. For instance, not all educators and motivation researchers share SDT’s assumptions of inherent intrinsic motivation and psychological needs and that learners universally benefit from autonomy support but suffer from interpersonal control (Chao, 1994; Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000). For two generations, SDT has eagerly embraced each new controversy (e.g. Do extrinsic rewards undermine intrinsic motivation? Do students in collectivistic nations benefit from autonomy need satisfaction? Is a controlling motivating style universally problematic?). With each published empirical study, the theory has amassed an incredibly successful track record to support both its theoretical assumptions and predictions.

Six Mini-Theories

SDT is the macro-theory that integrates its six mini-theories. SDT arose for a purpose, as each mini-theory was created to address, understand, explain and resolve a specific research question, as follows:

• Basic psychological needs theory: Does need satisfaction lead to effective functioning and well-being; does need frustration lead to maladaptive functioning and ill-being?

• Cognitive evaluation theory: How do external events affect intrinsic motivation?

• Causality orientations theory: What does self-determination in the personality look like? Do internal events affect motivation and functioning in the same way that external events do?

• Organismic integration theory: How differentiated is the concept of extrinsic motivation? Can degrees of internalization explain the different types of extrinsic motivation?

• Goal contents theory: Why do some goals generate more effort, progress and well-being than do other goals?

• Relationships motivation theory: Why do some relationships become close and deeply satisfying while other relationships leave partners defensive, insecure and unhappy?

Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT)

Basic psychological needs theory provides the SDT perspective on well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001, 2017; Ryan et al., 2008). To do so, BPNT highlights the motivational properties of the three universal psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness. Autonomy is the psychological need to experience personal ownership during one’s behavior. Its hallmarks are feelings of volition and selfendorsement. Competence is the psychological need to experience mastery during environmental challenges. Its hallmarks are feelings of effectance and a sense of making progress and stretching one’s skills and capacities. Relatedness is the psychological need to experience acceptance and emotional connection in one’s close relationships. Its hallmarks are feelings of closeness and authenticity (i.e. a sense that the person we are interacting with truly accepts us for who we are).

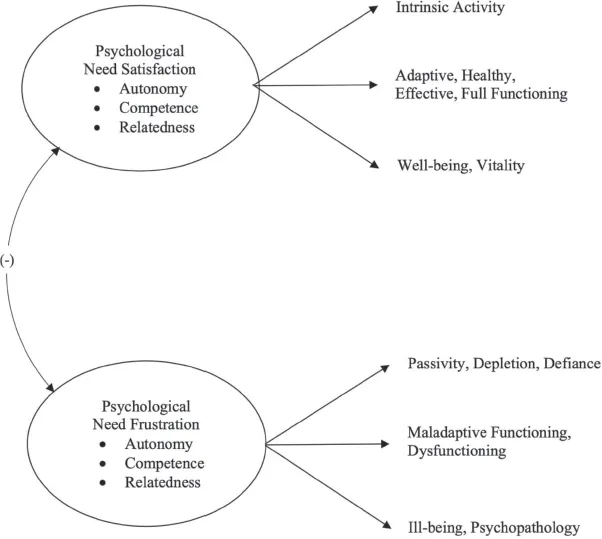

BPNT identifies psychological need satisfaction as the essential nutriment for wellness and flourishing. As shown in Figure 1.1, when these basic psychological needs are satisfied, flourishing occurs in terms of intrinsic activity, adaptive functioning and wellness. When these basic psychological needs are frustrated, functioning and well-being are impoverished in terms of passivity, defiance, maladaptive functioning, ill-being and even psychopathology. Need satisfaction and need frustration vary between persons, but they also vary within the same person over time, across contexts, and across different relationships. Fundamentally, any factor that enables moment-to-moment or situation-to-situation need satisfaction will produce corresponding gains in well-being, while any factor that produces moment-to-moment or situation-to-situation need frustration will produce corresponding gains in ill-being.

BPNT is at the center of cross-cultural research. Psychological needs are defined as inherent inner motivational resources that are necessary for optimal functioning, development, and well-being. SDT assumes that all three psychological needs apply to all individuals, irrespective of their nationality, culture, age, special need status or economic and political circumstances. Cultures and political systems do vary in their socialization styles – and, therefore, in their values, priorities, and norms – but need satisfaction is universally associated with well-being while need frustration is universally associated with ill-being (Chen et al., 2015; Chirkov et al., 2003).

Figure 1.1 Basic Psychological Needs Theory

Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET)

Cognitive evaluation theory provides SDT’s social psychological perspective (Deci & Ryan, 1980; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Its central motivational concept is intrinsic motivation. CET was created to explain how any external event (e.g. a reward, praise, an assessment, feedback) sometimes enhances but other times undermines intrinsic motivation, which is the inherent desire to seek out novelty and challenge, to explore, to investigate, to learn, to take an interest in activities and to stretch and extend one’s skills and capacities. For intrinsic motivation to be maintained or enhanced, certain types of experiences are required – namely, satisfaction of the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

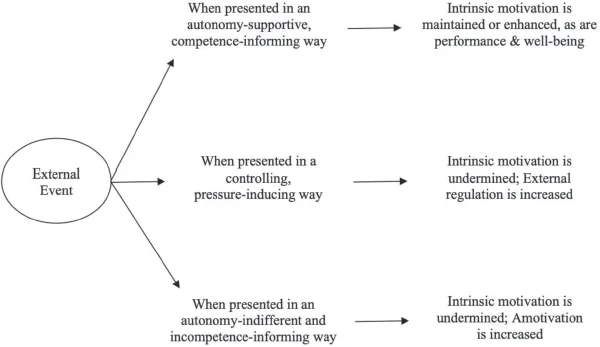

As illustrated in Figure 1.2, any external event can be offered in: (1) an autonomy-supportive and competence-informing way to maintain autonomy, enhance competence and therefore to enhance intrinsic motivation; (2) a controlling and pressure-inducing way to frustrate autonomy and therefore to undermine intrinsic motivation; or (3) an incompetence-communicating way to frustrate competence and therefore to undermine intrinsic motivation. The predictive power of CET to explain the ups and downs of intrinsic motivation has been demonstrated across a wide range of external events, including rewards (Deci et al., 1999), rules/limits (Koestner et al., 1984), choices (Patall et al., 2008), praise (Henderlong & Lepper, 2002), feedback (Mouratidis et al., 2010), verbal communications (Curran et al., 2013), goals (Vansteenkiste et al., 2004), assessment criteria (Haerens et al., 2018) and behavior change requests (Vansteenkiste et al., 2018). For each external event, the CET prediction is the same, because it is not so much what the external event is, as it is how it is administered.

Figure 1.2 Cognitive Evaluation Theory

CET’s explanatory range includes not only specific external events but also the larger interpersonal context (e.g. advisor-learner relationships, classroom climate, school atmosphere, national ethos). Just as an external event can be presented in an autonomy-supportive, controlling, or amotivating way, so can an interpersonal context. Autonomy-supportive contexts and relationships offer understanding, information and need-support; controlling contexts and relationships offer prescriptions, pressures and are need-thwarting; and amotivating contexts and relationships offer neglect, unfulfillment and needindifference (Bhavsar et al., 2019; Reeve & Cheon, 2021).

Causality Orientations Theory (COT)

Causality orientations theory provides SDT with a personality perspective (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017). COT proposes that, through their unique developmental histories, learners acquire varying levels of three causality orientations (autonomy, control and impersonal) that reflect acquired beliefs about what forces best initiate and regulate their behavior. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, COT proposes that all learners hold all three causality orientations but that their relative strengths vary from person to person. With an autonomy orientation, the learner treats the environment as a source of information that provides opportunities and action choices. When autonomy-oriented, students– learners are interest-taking, autonomously self-regulating, and rely on identified regulation, integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation to initiate and regulate their behavior. With a control orientation, learners become motivationally dependent on rewards, incentives, social controls and external contingencies as they need envi...