eBook - ePub

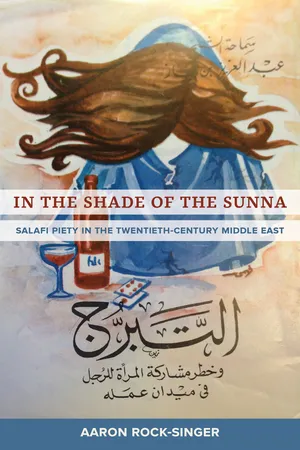

In the Shade of the Sunna

Salafi Piety in the Twentieth-Century Middle East

- 278 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Salafis explicitly base their legitimacy on continuity with the Quran and the Sunna, and their distinctive practices—praying in shoes, wearing long beards and short pants, and observing gender segregation—are understood to have a similarly ancient pedigree. In this book, however, Aaron Rock-Singer draws from a range of media forms as well as traditional religious texts to demonstrate that Salafism is a creation of the twentieth century and that its signature practices emerged primarily out of Salafis’ competition with other social movements amid the intellectual and social upheavals of modernity. In the Shade of the Sunna thus takes readers beyond the surface claims of Salafism’s own proponents—and the academics who often repeat them—into the larger sociocultural and intellectual forces that have shaped Islam’s fastest growing revivalist movement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In the Shade of the Sunna by Aaron Rock-Singer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Historia de Oriente Medio. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Roots of Salafism

Strands of an Unorthodox Past, 1926–1970

During the second half of the twentieth century, Ansar al-Sunna laid claim to four signature practices: praying in shoes, gender segregation, a distinctive approach to facial hair, and shortened pants or robes. As chapters 3 through 6 of this book will show, Egyptian Salafis understood these practices to emerge directly from the Quran and Sunna. This chapter seeks to answer a question that lies behind this story of practice: what are the historical conditions under which Salafi pious practice came to center on communication? Specifically, what are the material and perceptual shifts that made this project not merely technologically viable but also socially thinkable?

Previous scholars have emphasized Salafism’s engagement with a diachronic Islamic legal tradition, particularly an authenticated corpus of Sunni hadith reports1 and pre-modern authors such as Ibn Taymiyya and his student Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 1350).2 In this chapter, by contrast, I will explore the conditions under which Salafis came to cite these sources in the service of a distinctly twentieth-century project of social change. To do so, I will trace Ansar al-Sunna’s emergence at the intersection of nineteenth-century projects of subject formation and abstraction, the printing and distribution of classical legal texts of the Islamic tradition, and a rapidly changing social world in which traditional structures of religious authority and longstanding markers of piety held less sway. My goal is not merely to chart Ansar al-Sunna’s development, but also to explain the shared conceptual roots that bind Salafis to ideologically diverse competitors.

Accordingly, in the first section, I will synthesize secondary scholarship on late-nineteenth- to early-twentieth-century Egypt to set the stage for the rise of Salafism as a social movement, with particular attention to questions of communication and textual production. In the second section, I will explore the material conditions that both made possible and facilitated Ansar al-Sunna’s rise, most notably the production of a canon of approved Islamic texts and the development of a national network of mosques and branches through which these and other texts could be taught and distributed. The third section then situates Ansar al-Sunna among Islamic movements during this period, emphasizing its commitment to a particular interpretative approach and a related effort to marginalize if not eliminate longstanding and widespread religious practices that it considered to be unlawful innovations (bidʿa). In the final section, I sketch the transition from monarchical to secular-nationalist rule, with an emphasis on the ways in which Ansar al-Sunna maintained a quietist approach while focusing on the development of grassroots institutions. The chapter concludes at the end of the 1960s, with Ansar al-Sunna having established both the material and perceptual basis for an expansive project of Salafi piety, an achievement that proved crucial to its move beyond defined institutions from the 1970s on.

SALAFISM’S UNORTHODOX PAST

In the late nineteenth century, a call to precise bodily regulation emerged in Egypt alongside a valorization of the capacity of the individual to shape society’s broader moral state. This exhortation, however, came not from Islamic reformers but rather from British colonial rulers as they introduced new methods of discipline and subject formation. Timothy Mitchell draws on Michel Foucault’s theory of discipline as he argues that “Political order was to be achieved not through intermittent use of coercion but through the continuous instruction, inspection and control,”3 and individuals were asked to regulate their own bodies in a manner that upheld broader societal goals.4 Schools were central to this project, modeling both the ideal individual subject and a broader entity of society as students moved in a highly organized fashion through social space.5

A new system of visual representation was central to British colonial influence and rule. As Mitchell states:

The methods of organisation and arrangement that produce the new effects of structure . . . also generate the modern experience of meaning as a process of representation. In the metaphysics of capitalist modernity, the world is experienced in terms of an ontological distinction between physical reality and its representation in language, culture, or other forms of meaning. Reality is material, inert, and without inherent meaning, and representation is the non-material, non-physical dimension of intelligibility.6

While Mitchell’s argument has been critiqued for assuming the uncomplicated translation of theory into practice,7 the broader enframing effects of colonial influence and rule would shape subsequent ideological projects.

British colonial influence also introduced new notions of political and textual authority. As Mitchell explains:

Politics was a field of practice, formed out of the supervision of people’s health, the policing of urban neighbourhoods, the reorganisation of streets, and, above all, the schooling of the people, all of which was taken up—on the whole from the 1860s onward—as the responsibility and nature of government.8

Of particular significance to the calls to piety that followed, however, was the “ ‘governance of the self’ (al-siyāsa al-dhātiyya) . . . expressed in terms of hygiene, education, and discipline.”9 In short, by the end of the nineteenth century, a model of subjectivity premised on observable self-regulation had been established.

This model of self-regulation in the service of communal imperatives, though initiated by an external power, was consonant with aspects of the Islamic ethical tradition.10 In her recent study of Classical Islamic ethics, Zahra Ayubi argues that this tradition “focuses on inculcating virtue ethics within individuals, with the larger goal of creating ethical conditions in the household and broader society.”11 As in Mitchell’s case, the conceptual framework for ethics is that of governance (Arabic: Siyāsa; Persian: Siyasāt).12 This tradition pivots on the assumption that communal success is dependent on the “collective skills and trades” of its inhabitants.13 In the Islamic Classical tradition, however, virtue is achieved not through self-regulating order but through the performance of particular affective practices of love, compassion, and forgiveness, as well as the maintenance of boundaries of modesty.14 Furthermore, this tradition does not assume that the individual’s efforts to successfully regulate him or herself will corrupt the broader social order, and is comparatively unconcerned with the visible performance of virtue.15

The British colonial project also advanced notions of textual authority that stood in stark contrast to the traditional Islamic model, which pivoted on human relationships. Whether in the case of the recitation of hadith reports, the teaching of key texts of Islamic law (fiqh), or the adjudication of legal cases, the reliability of any given source—and the authority to transmit it—depended on its attribution to a chain of individuals deemed trustworthy.16 By contrast, colonial notions of writing assumed a mechanical understanding of authorial meaning that made human chains of transmission secondary if not irrelevant,17 an assumption that reflected the ambitions of a political project that sought to order Egyptian society in uniform fashion.18 This approach to the balance between textual clarity and human relationships, in turn, was successful not merely due to the political power of colonial authorities, but also because it had been preceded by a homegrown modernization project under the Ottoman governor of Egypt Muhammad ʿAli (d. 1839), which privileged written over oral evidence in legal proceedings.19

Ottoman efforts to regulate dress also contributed to the association of visual signs with particular allegiances and positions. Whereas the Egyptian army had previously donned varied garments, Muhammad ʿAli instituted a new system by which “soldiers were . . . to be set apart from the civilian community by their confinement and by the wearing of a uniform dress.”20 Uniforms further served to distinguish various ranks of soldiers within the army, reflecting the intersection of hierarchy and communication in a system that sought to anonymize its constituent members.21 Similarly, students in state institutions were expected to don distinct uniforms, including a dark blue shirt with a single row of buttons, bright red trousers, badges attached the collar’s front, and a tarbush on the head.22 The regulation of dress thus reflected not only the emergence of state-sponsored projects of subject formation, but also a linkage between clothing and membership in or allegiance to an abstract entity, here institutions controlled by the Egyptian state.

Just as modernization enabled the state to reach deeper into society, so too did it connect previously far-flung areas of Egypt. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century under the reign of Muhammad ʿAli’s fourth son, the Khedive Saʿid (r. 1854–63, d. 1863), Egyptians came to experience a world in which the country’s population was linked by the railroad.23 Similarly, the development of a national postal system facilitated the circulation of print media, particularly periodicals.24 In his study of Egyptian nationalism, Ziad Fahmy shows that these technological shifts, alongside urbanization, promoted the rise of Egyptian national identity, while enhancing the influence of key cities such as C...

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- The Ethics of an Orphan Image

- A Note on Transliteration and Spelling

- Introduction

- 1. The Roots of Salafism: Strands of an Unorthodox Past, 1926–1970

- 2. Conquering Custom in the Name of Tawhid: The Salafi Expansion of Worship

- 3. Praying in Shoes: How to Sideline a Practice of the Prophet

- 4. The Salafi Mystique: From Fitna to Gender Segregation

- 5. Leading With a Fist: The Genesis and Consolidation of a Salafi Beard

- 6. Between Pants and the Jallabiyya: The Adoption of Isbal and the Battle for Authenticity

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index