![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Decolonising the Roman grid

Sofia Greaves and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill

One day a man stepped forth called Hippodamos, a Pythagorean, and consequently learned in mathematics and a philosopher and an architect. He first opposed a scientific system of town planning to the old practice, as Aristotle tells us, κατα τòν νεώτερον τρόπον – the new method opposed to the old practice. He planned the town according to the rectangular system, and he divided the land – let me see, it must have been something like Hampstead Garden Suburb, so you know it all, and I need not describe it.1

These words, delivered by the German planner Rudolf Eberstadt at the world’s first Town Planning Conference held in London in 1910, represent a claim to an affinity between ancient and modern town planning that was widely shared by the delegates. Architects, engineers and medics saw in the urban environment a tool for improving society, after revolution, disease, population expansion and technological development placed this matter at the forefront of government concerns. At this Town Planning Conference, the first of its kind, over one thousand participants gathered from nations across the West, including Italy, France, Britain and the United States, so that they might study ‘the questions involved in our cities’ improvement and extension’.2

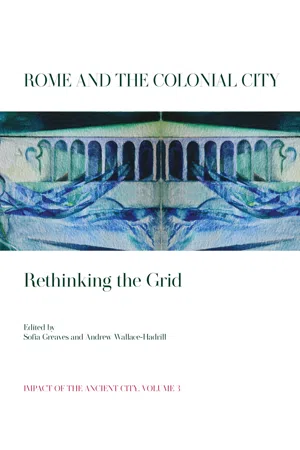

Aristotle does indeed tell us that Hippodamus of Miletus ‘discovered how to cut up a city’, though he had little patience for a figure he criticised as ‘a strange man’ and ‘not a statesman’.3 Eberstadt’s Hippodamus was instead ‘a philosopher and an architect’, allegedly just as rational as Raymond Unwin (1863–1940), planner of Hampstead Garden Suburb and author of Town Planning in Practice (1909). Eberstadt might be forgiven for falling into the widely shared misconception that Hippodamus was first to plan on the grid.4 Dr. Herbert Warren, President of Magdalen College Oxford, also told his students how ‘Aristotle tells us in “The Politics”, Hippodamus of Miletus, the famous philosopher and savant, invented town planning’.5 The plan of the recently excavated Miletus seemed to certify this hypothesis (Fig. 1.1).

However, Eberstadt’s misunderstanding was welcome to urban planners because Hippodamus ‘stepped forth’ just like the architects of his generation. Hippodamus ‘the architect’ provided them with an ancient ancestor who lent weight to their assertions that ‘it is as a branch of architecture that the Town Planning movement will go down to posterity’.6 Aristotle’s Hippodamus, who applied ‘a scientific system of town planning to the old practice’, also verified the superimposition of new ‘rational’ schemes over other settlement types. It could be argued that since ‘the birth of planning’ such settlements had always been deemed ‘unplanned’. This notion legitimised the erasure of ‘the old practice’ in present day: ‘the laissez-faire period of town growth corresponding to the last half of the last century [which] has proved its wastefulness as well as its hideousness’.7

Figure 1.1. Plan of Miletus, as published in Haverfield, Ancient Town-Planning, 45, fig. 9.

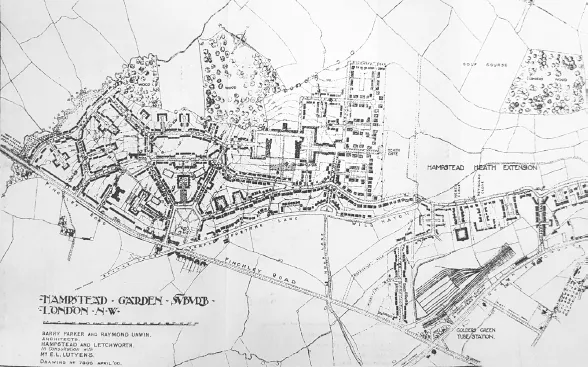

A cursory glance at Hampstead Garden Suburb (Fig. 1.2) and the supposedly Hippodamian Miletus (Fig. 1.1) immediately shows that Eberstadt made a questionable generalisation. Hampstead was clearly not laid out on ‘the rectangular system’. Hampstead was indeed laid out according to a very specific sequence. First the topography was surveyed, second the position of all the trees was devised and finally the central square was laid out. Then followed public buildings and the ‘wide avenue’ which formed its central axis.8 We cannot know how Hippodamus ‘planned’, because no treatise survives, but suddenly Hampstead – a new scheme following a unique logic – found legitimacy in an ancient, Hippodamian precedent.

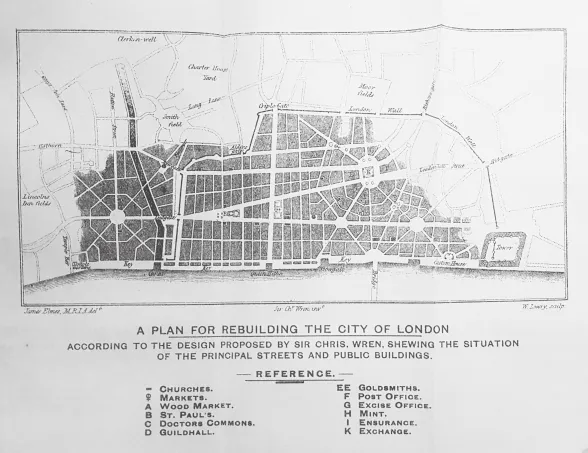

To some extent it was unsurprising that Eberstadt and others chose to discuss ancient urbanism in the context of the Town Planning Conference. Greco-Roman writers left a legacy of texts which discussed urban layout and aesthetics, with the result that the subject of ancient town planning had long been debated in the Western tradition. Vitruvius, author of the de Architectura, the only extant Roman architectural treatise, taught how to build an ideal city.9 Renaissance writers Alberti and Averlino Filarete interpreted Vitruvius for their world, adding their own diagrams. Even if their presentation of the ideal layout as radial and octagonal derived from their misinterpretation of the Latin text, these diagrams built upon and became a part of Vitruvius’ legacy.10 The reception, transmission and interrogation of Greco-Roman ideas about cities also legitimised later theories and planning projects, from Palmanova (1658) to London, reimagined by Christopher Wren after the fire of 1666 (Fig. 1.3). This process continued up to the conference in 1910, where we can also hear clear echoes of Vitruvian paradigms for the healthy city in the words of Ebenezer Howard, author of Garden Cities of To-morrow, who emphasised that ‘The most essential needs surely are adequate space, light and air. No city will ever be an ideal city unless it provides those essential conditions for all the people’.11

Figure 1.2. Hampstead Garden Suburb, plan drawn by Edward Lutyens. Unwin designed Letchworth Garden City in 1903, after which he designed Hampstead Garden City in 1905.

Figure 1.3. Christopher Wren’s ‘A Plan for Rebuilding the City of London’, 1666. Unbuilt. Reproduced in the Members’ Handbook given to attendees of the Town Planning Conference, London, 1910. Members’ Handbook, 8.

Planners of Howard’s generation looked back to antiquity for solutions because they hoped to civilise society, ‘to sweep away the poisonous atmosphere of the dens of infamy’, and to make ‘better citizens, better men’.12 They continued a process which has progressively reshaped the very idea and legacy of ‘the Roman city’ in material and conceptual ways.

For example, comparisons between Hampstead and a Hippodamian city continued a process of distorting the very image of the latter. Just as Hampstead was now linked to Hippodamian cities, Miletus was associated to Hampstead Garden Suburb. This introduction began in the Edwardian period because it represented a crucial moment in this tradition of reinterpretation; as a result of the interaction between disciplines, which occurred within the domain of ‘the city’, the reconceptualisation of ancient and modern urbanism occurred simultaneously and symbiotically. Architects, engineers, medics and archaeologists worked alongside each other and were influenced by one another. They shared an intellectual framework because they were educated in the classics and were therefore receptive to similarities between their practice.13 Planners were interested in and exposed to archaeological material because it seemed relevant. Antiquity also underpinned their discipline, which was preoccupied with public health infrastructure; for example, excavations in Pompeii and Ostia clearly showed that Greco-Roman cities had (already) possessed straight streets, water distribution, public fountains, sewers, private pipes, toilets and baths.14 Equally, archaeologists were involved in urban planning processes, which facilitated excavation and necessitated a memorialisation of the ancient past. Their excavations and publications were consequently influenced by assertions such as Eberstadt’s. The picture of the ‘Greco-Roman city’ formulated in this period was deeply shaped, both conceptually and materially, by nineteenth-century preoccupations and what we might term ‘the modern city context’.15 As a result, the modern city and ancient city came to reflect one another; our picture of ancient urbanism has been rationalised, regularised, even ‘sanitised’.

The Town Planning Conference provides an excellent case study through which to explore this problem. The conference began with ‘Cities of the Past,’ which had long been, by their definition, the cities of Greece and Rome despite their broader knowledge of ancient civilisations.16 Here, British archaeologists Francis Haverfield and Thomas Ashby presented ‘the Roman City’, while Percy Gardner covered ‘the Greek city’.17 German art critic Albert Brinckmann presented ‘The Evolution of the Ideal in Town Planning since the Renaissance’.18 Papers then progressed, chronologically, through the ‘Cities of the Present’ to ‘Cities of the Future.’ The structure schematised and simplified cities into periods and models, creating ‘a certain logical scheme’, in order to construct an understanding of civilisations with practical value. As Leslie Cope Cornford19 summarised it: ‘If those who build the city of the future will take what serves their need from the cities of the past, what they shall build will be a new thing answering to the new need.’20

The archaeologists and historians who were present at the conference openly encouraged the notion that modern urbanism had been ‘inherited’ from ancient Greco-Roman practice. Brinckmann believed that Rome brought about the birth of town planning, claiming, ‘The influence of Rome is immense. If it had not been for the efforts of that city modern town-planning would be inconceivable’.21 He argued that post-Roman urbanism owed its forms to antiquity, ‘The development of the idea of town planning, conceived in Rome, was taken up by France and above all by Paris, under a monarchy which looked upon the architecture of its towns as the highest expression of its power’.22

Similarly, Francis Haverfield indicated that ancient Roman planning embodied the same aesthetic concerns as contemporary planners.

The great gift of the Roman Empire to Western Europe was town life and during the Roman Empire the creation of new towns went on a pace … Ancient life I think, differed from modern in nothing so much as in its preferences for set and almost crystallised forms within which to express itself. This is specially seen in the form given to the town.23

Haverfield also echoed Eberstadt’s ideas about Hippodamus, who was for him ‘first of all architects’ and took an interest in the town as a ‘harmonious whole centered around the market-place’.24 Gardner similarly read the Hippodamian grid as an expression of public health concerns, believing that Hippodamus ‘the architect’ showed, ‘the course of the ancient world is in many ways parallel to that of the modern world’.25 He projected modern logic onto the ancient grid plan, arguing that, ‘As with us, so among the Greeks, there was a contrast between the old cities with their narrow and crooked streets and the new cities with their unity of plan and search for convenience’.26 This showed, in Gardner’s words, that ‘Architecture...