eBook - ePub

The Venice Ghetto

A Memory Space that Travels

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Venice Ghetto

A Memory Space that Travels

About this book

The Venice Ghetto was founded in 1516 by the Venetian government as a segregated area of the city in which Jews were compelled to live. The world's first ghetto and the origin of the English word, the term simultaneously works to mark specific places and their histories, and as a global symbol that evokes themes of identity, exile, marginalization, and segregation. To capture these multiple meanings, the editors of this volume conceptualize the ghetto as a "memory space that travels" through both time and space.

This interdisciplinary collection engages with questions about the history, conditions, and lived experience of the Venice Ghetto, including its legacy as a compulsory, segregated, and enclosed space. Contributors also consider the ghetto's influence on the figure of the Renaissance moneylender, the material culture of the ghetto archive, the urban form of North Africa's mellah and hara, and the ghetto's impact on the writings of Primo Levi and Marjorie Agosín.

In addition to the volume editors, The Venice Ghetto features a foreword from James E. Young and contributions from Shaul Bassi, Murray Baumgarten, Margaux Fitoussi, Dario Miccoli, Andrea Yaakov Lattes, Federica Ruspio, Michael Shapiro, Clive Sinclair, and Emanuela Trevisan Semi.

This interdisciplinary collection engages with questions about the history, conditions, and lived experience of the Venice Ghetto, including its legacy as a compulsory, segregated, and enclosed space. Contributors also consider the ghetto's influence on the figure of the Renaissance moneylender, the material culture of the ghetto archive, the urban form of North Africa's mellah and hara, and the ghetto's impact on the writings of Primo Levi and Marjorie Agosín.

In addition to the volume editors, The Venice Ghetto features a foreword from James E. Young and contributions from Shaul Bassi, Murray Baumgarten, Margaux Fitoussi, Dario Miccoli, Andrea Yaakov Lattes, Federica Ruspio, Michael Shapiro, Clive Sinclair, and Emanuela Trevisan Semi.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Venice Ghetto by Chiara Camarda, Amanda K. Sharick, Katharine G. Trostel, Chiara Camarda,Amanda K. Sharick,Katharine G. Trostel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Italian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2022Print ISBN

9781625346155, 9781625346148eBook ISBN

9781613768914Part I

The Archive

Rooted Memories

Chiara Camarda, Federica Ruspio, Amanda K. Sharick, and Katharine G. Trostel

There are several myths attending the archive. One is that it is unmediated, that objects located there might mean something outside the framing of the archival impetus itself. What makes an object archival is the process whereby it is selected, classified, and presented for analysis. Another myth is that the archive resists change, corruptibility, and political manipulation. Individual things . . . might mysteriously appear in or disappear from the archive.

—Diana Taylor, Archive and the Repertoire

Chapter one

Hebrew Books in the Venice Ghetto

Chiara Camarda

This essay summarizes two years of cataloging and researching the early Hebrew book collection of the Renato Maestro Library and Archive in the Venice Ghetto. Starting from information provided by the catalog, we can trace the history of this library, situating it within its cultural context. Given the impressive historical background of Hebrew printing in Venice, one enters this library with great expectations and curiosity. Many books in the present-day collection have been printed, sold, studied, and kept in Venice across the centuries and are still part of the heritage of this Jewish community. Even a quick visit, however, gives a sense of negligence and isolation: few readers are inside, employees and volunteers are asked to open its doors only on occasion, and no cultural events take place to draw attention to its holdings. This is a frozen memory space that contains early books as well as modern collections, but misses its target.

Located in the Campo del Ghetto Nuovo, next to the Jewish Museum, this library owns 2,373 catalogued volumes printed between the sixteenth and the twentieth centuries.1 Of these volumes, a total of 226 editions were published in Venice, a surprisingly small number considering the ceaseless activity that characterized Venetian print shops for about three centuries. The earliest book in this collection is the third volume of Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi’s Sefer Rav Alfas printed by Daniel Bomberg in 1522, but according to old inventories, earlier volumes were extant up to the beginning of the twentieth century.

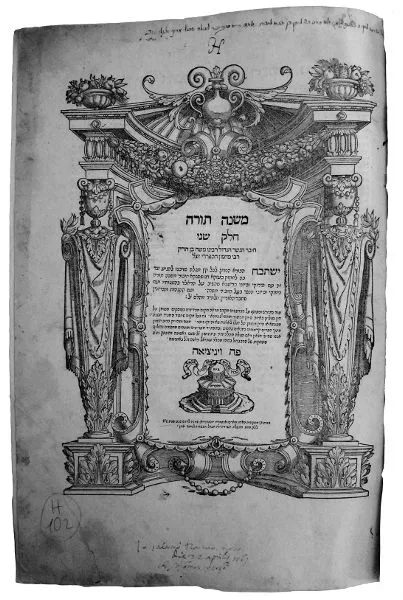

FIGURE 6. Maimonides, Moses, Mishneh Torah (Venice: Giustinian, 1550, s. m. C.G2.01), Venice, Renato Maestro Library and Archive.

—Photograph by Chiara Camarda.

Over the last several years, my research has focused on tracing the history of these volumes, to determine what part of the prolific Venetian production could still be found in situ, to make a list of the missing books, and to identify the provenances of the copies.2 Therefore, while compiling the catalog, I concentrated on the provenance of books as part of my doctoral thesis, trying to identify former owners and old collections that were donated to this library. It was not easy to locate this information: very little evidence can be found in the community’s archive, and in some cases, I had to rely on the memories of witnesses.

Once the cataloging and the research were complete, I asked myself why such an important treasure had been neglected for such a long time, leading to the deterioration of some volumes and the loss of others. Of course, this case is not unique: many Italian (Jewish and non-Jewish) institutions share similar conditions. They all lament the lack of monetary and human resources that would enable them to grant access to the public—and beyond that, to enhance and enrich their collections. Few libraries dedicate any of their budget to collection enhancement, as funds are often barely sufficient to cover the expenses of primary services.

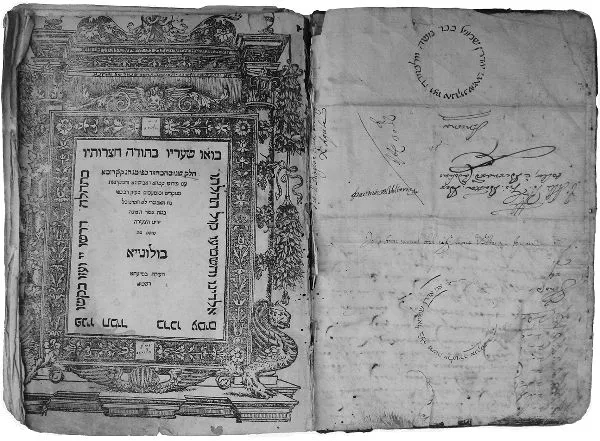

FIGURE 7. Maḥazor (Bologna: Refa’el Talm i, 1540, s. m. C.M2.15.B), Venice, Renato Maestro Library and Archive.

—Photograph by Chiara Camarda.

Considering how few people visit the Renato Maestro Library—and that those who do typically consult the archive rather than the Judaica collection—another question emerges: Is this early book collection actually representative of the education and training of the Venetian Jewish community of the past? Some years ago, a rabbi came to the library asking about Talmud editions that could be useful for his students: he found none. All of them were obsolete. The same thing happened with prayer books; when new ones were bought for one of the synagogues, the old ones were donated to the library. What does a library do with many copies of the same edition? As they are early books, they cannot be disregarded as useless duplicates, for their margins and blank pages may serve as archival sources to collect information about the members of the local community in a specific period. The printed catalog of the early books includes a detailed index of the provenances found on the marginalia of the copies, a useful key to quickly find this archival information.

We will now dig deeper into the Hebrew book collection of the Renato Maestro Library, an institution that inherited the collections of the former Talmud Torah Library and keeper of the bibliographic treasures that survived this community’s vicissitudes until the present day. Venice is especially relevant for the history of Hebrew books. Hundreds of accurate and beautiful editions were issued by its well-known printers and sold all over Europe and the Mediterranean. One would expect the Venetian Jewish community to own a large and rich collection of such editions, as they were printed not far from the Ghetto (mainly in the Rialto area) and they were in Hebrew, but on the contrary, looking at the shelves containing the 2,373 early Hebrew books, one might think: That’s it? That’s all that remains? Through my investigation, I try to determine why this collection is so small, the actual impact of Hebrew printing in the Venetian context, where these books come from, and why many items that were part of this collection are now missing.

To explain why Venice was so important in the field of Hebrew book production and trade, we will follow the history of Hebrew printing in the Venetian lagoon from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, when it faced an irreversible decline. Then, looking at the context of the local Jewish community, we will concentrate on the public and private book collections acquired by the Renato Maestro Library. Finally, we will trace the history of this library with the help of archival and bibliographic sources, oral history, and provenance-related information that can be found in the blank pages and in the margins of the volumes. This kind of information can be very useful in identifying the locations of book collections across time; learning about their readers, owners, or curators; and understanding how the current collection formed and grew.

Sixteenth-Century Venice: The Cradle of Hebrew Printing

Many people have written about Venice and its Ghetto from different perspectives: scholars, writers, and journalists; Italian and foreign Jews visiting Venice as part of their collective cultural history; students from all over the world; Venetians who claim ownership of the space because they are writing about their own city; and so forth. From the vantage point of a librarian, historical investigation begins with the books and the archives. I approached the Renato Maestro early Hebrew book collection with trepidation and excitement, knowing that I was holding centuries-old volumes that had survived many generations and aware that I had the responsibility of introducing them to the public through new online and paper catalogs.3

Why was this project so important? The reading public of a given collection housed at a library or a particular archive is much broader and geographically scattered today than it once was, when the heritage of small Jewish communities was destined to be used only by its own community. While the birth and death records are still consulted by local Jews and descendants of former community members (mainly to create family trees), few people are interested in studying the bibliographic and archival collections as a whole or in detail, which is now the role of scholars and researchers. For these new audiences to find this material (and for the material to be found by its readers), it is necessary to update the online resources and online public access catalogs (OPACs) of each institution and to divulge as much of the collection’s content as possible through the publications of edited catalogs and descriptions of the preserved documents. The second, and more particular, reason that this specific archive is so important is that Venice was the cradle of Hebrew printing, the place where the first stable Hebrew press was opened.4

Although a few examples exist of Hebrew books printed elsewhere in Italy before this period, they were rare attempts, with the sole exception of Gershom Soncino’s wandering press, which printed many volumes in different towns. Soncino became recognized for the quantity and high quality of his publications; however, economic competition forced him to leave Italy for the Ottoman Empire. Although he wished to, he was never able to bring his business to Venice.5

The Serenissima Repubblica, home of Aldo Manuzio, the most famous Greek and Latin printer of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, was fertile ground for this new activity. Manuzio himself promised to print Hebrew books and issued some sheets in Hebrew characters as well as a sample page for a Hebrew edition of the Pentateuch, but he was hesitant to invest in Hebrew printing given its lack of popularity among mainstream audiences.

Though Manuzio abandoned the project, Daniel Bomberg seized the chance to have his name forever associated with the greatest Venetian Hebrew printing press. Bomberg originally arrived as a merchant from Antwerp, seeking to expand his trade in the Venice port. His friend Felice da Prato, a converted Jew, convinced him to establish a Hebrew press, and he embraced this visionary project by strategically investing in making Hebrew printing both profitable and functional. As time passed, it became clear that this work was not mere business for Bomberg; what emerges from the reading of his biographies is that Hebrew printing became his life’s mission.6 It is widely speculated that Bomberg studied Hebrew and kept close friendships with some of his workers, especially with Cornelius Adelkind (who even named his son Daniel after his employer).7

Bomberg’s print shop would go on to issue the major works of the Jewish literary tradition and is remembered particularly for publishing the first complete editions of both the Babylonian and the Palestinian Talmud, making available for the first time on a large scale two cornerstones of Jewish oral law; manuscript copies of the entire works were extremely expensive and rare. Wishing to provide the best possible edition of any work he printed, Bomberg sent one of his workers around Europe and the Mediterranean looking for different manuscripts of the texts that he intended to publish, financing their purchase and collation. In addition, he attended to the aesthetics of his books in terms of paper quality, typeset, and woodcut decorations and reached a formal perfection that could hardly be surpassed.8

The Venice Ghetto attracted scholars from different communities, and experts on Hebrew classical literature found themselves gathe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- A Note on the Essays

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Contributors

- Index