- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

In this powerful new book, James Rickabaugh, former superintendent and current director of the Institute for Personalized Learning (IPL), presents the groundbreaking results of the Institute's half-decade of research, development, and practice: a simple but powerful model for personalizing students' learning experiences by building their levels of commitment, ownership, and independence. Tried and rigorously tested in urban, suburban, and rural districts--and in different academic and economic settings--the IPL model has been proven to enhance student engagement and achievement at all levels. Rickabaugh provides principals and other top-level leaders with * Step-by-step guidance for implementing the model;

* A detailed overview of the research and work behind the model's development;

* A complete introduction to the heart of the model—a comprehensive, multi-layered framework centered on the three core components of learner profiles, customized learning paths, and proficiency-based progress;

* Tools and activities for assessing and adjusting the model to meet the specific needs of students and staff;

* Strategies for increasing and reinforcing enthusiasm for the change process among everyone involved, from the classroom to the greater community; and

* An abundance of real-life examples and reflections from students, teachers, principals, and superintendents whose schools have flourished in record time and with minimal additional funding or resources. Tapping the Power of Personalized Learning offers a blueprint that dramatically improves student outcomes and prepares today's learners to meet life's challenges in college and beyond.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Assumptions, Logic, and Levers: Changing Practices

As we continued to push new models, it was clear that everybody had an assumption about school: teachers, parents, principals, and students. These assumptions were so powerful that any changes were always met with a need for assurance that things would be "better." This was the very moment that became the tipping point. I asked just one question: "Can you tell me about a time where you were part of an effective learning experience?" First of all, everyone had a story, but even more importantly, everybody could articulate a powerful personalized learning experience.

—Ryan Krohn, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction/education accountability, School District of Waukesha, Wisconsin

It's funny how change can sneak up on you in unexpected ways. Our partnership with the Institute for Personalized Learning opened a door that allowed us to dream big—to rethink education as we had experienced it up to this point. We could overhaul our teaching strategies and the environment in which we support students. We were able to take the ceiling off of our teaching and reach our students in ways we never had before.

With administrative support to try new things, we have been able to take risks with our instruction and with our students. We are now free to "fail forward." The power has now shifted from us being the sole deliverers of instruction, to our students giving voice to what that instruction will look like. They are now copilots in our learning journey. The results have been more than we could have expected: Our students are engaged, we are engaged, and the things that our students know and do truly show that they are on the road to being strong 21st century learners.

Now that year 2 of our personalized learning journey is coming to a close, we cannot imagine teaching any other way. We are invigorated. We are passionate. We are continually looking for ways to improve—not for us, but for the greater good of our students.

—Kate Sommerville & Angela Patterson, 5th grade teachers, Swanson Elementary School, Elmbrook School District, Wisconsin

The Power of Assumptions

- Practice: Grouping learners by age and moving them through the system in batches. Assumption: Students learn at the same rate and are ready for new learning at the same time as others born in the same year.Fact: Each student learns at his or her own pace based on level of interest, learning history, maturity, and background knowledge.What if…we gave students the support they needed to learn at a pace dictated by their individual readiness rather than by their ages?

- Practice: Using the same instructional approaches for entire groups of learners. Assumption: Ability to keep pace with the class and learn from a set of standard instructional strategies is a good measure of learning aptitude.Fact: Not all students learn in the same ways, and teaching them as though they did makes it inevitable that some will be held back when they're ready to move forward while others will struggle to keep up.What if…we gave students the time they needed to learn and the support necessary to learn in the ways that best fit them?

- Practice: Waiting for learners to fail repeatedly before providing "remediation." Assumption: Failure is inevitable for some, and learners who fail need to be "fixed."Fact: We don't have to wait for students to fail repeatedly before adjusting instruction to their learning needs, and "fixing" should begin with the instructional strategies.What if … students were able to learn the way they learn best from the beginning and could receive the support they need in real time, as they're struggling?

- Practice: Attempting to capture learning performance and progress through credits and letter grades. Assumption: It isn't necessary to be specific when reporting what students have learned; a general indication of what the educator judges as unsatisfactory, satisfactory, or exemplary is enough.Fact: Credits and grades tell us little about the nature and level of current student learning. At best, credits are general indicators of progress, and grades are too often contaminated by factors unrelated to learning.What if…learners had access to immediate feedback and were able to track their progress against standards in detail and in real time, all of the time?

- Practice: Using a system of rewards and sanctions to control student behavior. Assumption: Students will not choose to learn without either the promise of rewards or the threat of sanctions.Fact: Students show us constantly that they will choose to learn what they see as relevant, purposeful, interesting, and challenging. We only need to watch learners who appear bored and disconnected at school engage in social media, video games, and extracurricular activities to see that they can be motivated to commit deeply. Further, when we send learners the message that we don't believe they will choose to learn without external motivators in place, we communicate that the learning isn't worthwhile on its own.What if…the incentives and supports we offered to students were designed to develop self-regulatory skills and an internally driven commitment to learn?

- Practice: Administering standardized tests and assessments that focus almost exclusively on content knowledge. Assumption: Knowing names, dates, places, sequences, and formulas is enough.Fact: It isn't enough to define learning as simply memorization and recall of information. Technology has made memorization less necessary than it used to be, and much of what we might ask learners to memorize today may no longer be relevant or even accurate in the future. Further, when we allocate significant portions of learning time to low-level activities such as memorization and recall, we waste time that students could dedicate to building skills and learning capacity. These are competencies that will serve learners well in situations where problems are not neatly defined and challenges demand deeper understanding and creative, flexible approaches.What if…learning and teaching were focused on building the learning skills and capacity necessary to thrive in a rapidly changing future, with specific content serving to provide context for learning application?

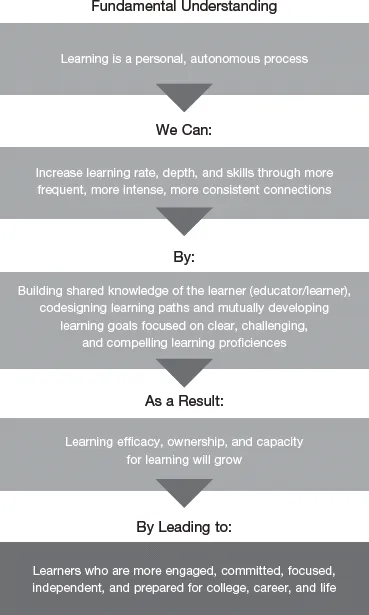

The Logic of Personalized Learning

Figure 1.1 Personalized Learning Logic Model

Employing the Right Levers

- Structures: Organizational options, tools, and logistics

- Samples: Student grouping options

- Standards: Expectations and progress benchmarks

- Strategies: Interactions that produce learning

- Self: Student and teacher beliefs about learning and their roles in learning

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Imagine Schools Where …

- Chapter 1. Assumptions, Logic, and Levers: Changing Practices

- Chapter 2. The Honeycomb Model

- Chapter 3. Personalized Learning from the Students' Perspective

- Chapter 4. The Five Key Instructional Shifts of Personalized Learning

- Chapter 5. Building Educator Capacity: Personalized Professional Development

- Chapter 6. Secrets to Scaling and Sustaining Transformation

- Appendix A: An Action Plan for Implementation

- Appendix B: Sample Design Principles

- Appendix C: Personalized Learning Skill Sets for Educators

- References

- About the Author

- Copyright