![]() Part 1

Part 1

What's Wrong with Professional Learning?![]()

Chapter 1

Accountability: Why Autopsies Do Not Improve Patient Health

Imagine that you received the following announcement from your local physician and hospital:

In a sharp break with tradition, we have decided to start using evidence to make our medical care decisions. We will evaluate carefully the available data and, in the future, engage in more of the practices that improve health and fewer of the practices that appear to kill people.

Would you find this announcement reassuring? Perhaps, on the contrary, you would exclaim, "Isn't that what you have been doing in the past?" The astonishing fact is that evidence-based decision making in medical care is innovative (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2006). Moreover, the most detailed medical evidence on the individual level is the autopsy, a procedure that is undoubtedly filled with data but that rarely improves the health of the patient. There are, of course, exceptions to every rule. In one famous courtroom exchange, the cross-examining attorney asked the medical examiner who had performed an autopsy, "And how did you know that the patient was dead?" The pathologist replied, "Well, his brain and heart had been removed and were in a jar, but I suppose that it's possible that he is out practicing law somewhere."

The Limits of Effect Data

While crime shows captivate television audiences around the globe, viewers would be puzzled by the amiable coroner who announces to the patient, "I've learned what's wrong with you, so just be careful the next time you cross the railroad tracks and you should be fine tomorrow morning." This scenario is no more absurd, however, than the accountability czars who tell schools many months after the end of the school year precisely what was wrong with student achievement. Consider the following typical time line for a process that is euphemistically called school improvement:

- May 15—Students are tested.

- June 30—School improvement plans are due, designed to explain how student achievement in the next year will be better than in the previous year.

- September 1—The superintendent opens the new school year with a declaration that teachers and school leaders must be committed to using data to drive instruction. After the speech, teachers listen to yet another workshop presenter extol the virtues of data, yet no one in the room possesses a single shred of authentic student data that teachers can use to improve teaching practice. "We've got it," they think. "Data good; ignorance bad. Is there anything else before I get back to my classroom to prepare for 35 students tomorrow?"

- October 1—The data that might have informed the June plan or enlightened the September speech at last arrive at schools and classrooms. Unfortunately, teachers are looking at data for students who were in their class the previous year.

- October 2—The local newspaper prints yet another article on the continuing failures of teachers and school leaders.

Some states, no doubt with good intent, have chosen to administer tests in the fall so that they can attempt to provide data to schools in time to influence the current group of students. This policy choice, however well intentioned, has failed. First, test results from the early months of the school year are not a reflection of current curriculum but the outcome of learning attrition over the summer. Second, even these well-intentioned states deliver the data months after the tests, providing data that masquerades as "formative assessment" five or six months into a nine-month school year. Third and most important, the states using fall tests make the dubious claim that they are attempting to provide diagnostic feedback for schools but use the same data to provide evaluative data to the federal government. Thus schools are designated as successes or failures based not on a year's worth of work of teachers and administrators but on six weeks of frantic test preparation.

Assessing the Causes of Learning

Effects are preceded by causes. This statement, obvious in its simplicity, illustrates the central error in current régimes of accountability not only in the world of education but in business as well. As the international economic meltdown that began in 2008 attests, it is entirely possible that organizations with outstanding results can suffer cataclysmic failure when the world is focused only on effects and not on causes. Enron was heralded as one of the most innovative and successful companies in the world in the months before it was insolvent (Neff & Citrin, 1999). Companies that were profiled as successes in such influential books as Good to Great—required reading for many leaders in the business, education, and nonprofit sectors—have evaporated (Collins, 2009). We gush with enthusiasm for effects—"Just show me the results!"—but pay little attention to causes. Our attention is diverted to the Scarecrow as he receives his diploma, but we pay no attention to The Man Behind the Curtain.

If this is common sense, then why is it so uncommon? Some states, such as North Carolina, have been remarkably candid about the distance between their aspirations and their accomplishments, and they regularly challenge education leaders to consider the distance between what they claim is important and what they actually do (Reeves, 2009a). The more common practice, however, is the use of blame as a strategy. "The feds made us do it!" cry the states, and school districts and individual schools echo the excuse as they post test scores in charts and graphs that are increasingly colorful and elegant and decreasingly relevant. The practical result of an overemphasis on effect data is reflected in the following conversation:

Susan: I've got it: dropouts are a problem. Ninth grade failure rates are too high, and students who are overage

for their grade level and have insufficient credits to graduate with their classmates are most likely to drop out.

Ron: Right.

I'm pretty sure we've known that for a long time. So tell me, Susan, how will next year's curriculum, assessment, and intervention policies for

our 9th grade students be different than they were last year? Can we do something new today with regard to literacy intervention, student

feedback, engagement, and attendance that will improve performance next year?

Susan: It's too late to make any changes.

Ron: But after a student has multiple failures in 9th grade, then we can make some changes?

Susan: Yes. That's the way we have always done it.

Ron: Then why would we expect next year's results to be any better?

Susan: If you're going to be difficult, I'm sending you to a mandatory workshop on 21st century school change.

Patterson, Grenny, Maxfield, McMillan, and Switzler (2008) demonstrated impressively the value of a study of "positive deviance," a powerful research method involving a consideration of cause data next to unexpected effects. An example of positive deviance cited by Patterson and his colleagues involves a study of data related to people suffering from Guinea worm disease. One important value in the study was the observation of how an effect—remarkably less frequent incidence of the disease—could be attributed to causes—behavior differences between the disease-ridden and the relatively disease-free populations despite similar culture, demographics, and economic conditions. Similarly, studies of high-poverty schools that fail are yesterday's news (Coleman et al., 1966), but studies that reveal consistent practices among high-performing, high-poverty schools (Chenoweth, 2007; Reeves, 2004b) consider not only effects but causes. To be sure, a consideration of causes is always a complex matter. Some causes are

beyond the control of schools (Rothstein, 2004), whereas other causes are within the sphere of influence of teachers and school leaders (Marzano, 2007; Marzano & Waters, 2009).

This appeal to consider cause data as well as effect data may seem a statement of the obvious. After all, if our objective were to address the teen obesity crisis in North America, we could probably create a more thoughtful program than one consisting of weighing students on May 1 each year, lecturing them in September, and giving them meaningful feedback six months after we last observed them inhaling a bacon cheeseburger. Think for a moment, however, about the extent to which that scenario is any different than knowing—with absolute certainty—in April and May that students need personal intervention and academic assistance but failing to give them any variation in teaching, feedback, or assessment until they experience yet another round of failure and disappointment.

If we expect teachers and school leaders to improve professional practices and decision making, then we must first give them different knowledge and skills than they have received in the past. This common sense, however, is routinely ignored by school leaders and policymakers who validate effects without considering causes.

Consider the case of the high school leader who is absolutely committed to greater equity and opportunity and therefore has undertaken a campaign to increase the number of students who will take college entrance exams. This leader knows that the very act of preparing for and taking those exams—typically the ACT, the SAT, or the A-Levels in Europe—will lead to a process of communication with colleges that will magnify the probability that the student will engage in studies after high school. Students who have traditionally been underrepresented in college will qualify for scholarships; others will receive invitations for interviews and campus visits. As a result, more students will focus on the opportunities and rewards of postsecondary education.

What could possibly go wrong with such a well-intentioned plan? Quite a bit. Compare this school leader with a colleague who is focused intently on effect data—average scores on college entrance exams. The colleague knows that the best way to boost the average is to encourage counselors and teachers to guide only the best-prepared students—perhaps the top 20 to 30 percent—to take those exams. Other students are told in both subtle and direct ways that if they apply to a nonselective college, they need not engage in the expense and demands of the exams. The first leader expands opportunity and equity, while the second leader limits those qualities. Who is the hero?

The newspaper headlines will excoriate the first leader for a disgraceful decline in the average test scores, and the second leader will receive rewards and recognition for another year of rising average scores. There is no adverse consequence for the second leader, who engaged in a systematic effort to diminish opportunity and equity, and there is no positive consequence for the first leader, who sought to do the right thing. In an environment where only effects matter, causes are dismissed as irrelevant. There is a better way, and that is the focus of the remainder of this book.

The Leadership and Learning Matrix

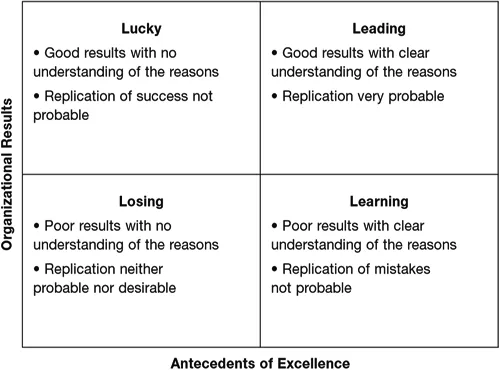

Figure 1.1, The Leadership and Learning Matrix, offers a practical way to consider both effect data and cause data. Student results—typically represented as a percentage of students who are proficient or another appropriate reflection of effect data—are plotted on the vertical axis. The horizontal axis is a representation of the "antecedents of excellence" (Reeves, 2004b; White, 2009), the measurable variables in teaching and leadership that are associated with student achievement.

Figure 1.1. The Leadership and Learning Matrix

The upper-left quadrant of the matrix, Lucky, represents schools that have good results and little or no understanding of how those results were achieved. This is not atypical of suburban schools that are host to a daunting number of instructional initiatives and dominated by widely varying teaching strategies. The dizzying array of teaching and leadership styles is defended because the various styles "work"—and evidence of that claim is the invariably high annual test scores. Students in these schools were born into a print-rich environment, were reading before they entered the school system, and when they run into academic trouble, receive healthy doses of parental support and private tutoring. By such logic, physicians are effective in their practice as long as they limit their practice to healthy patients.

The lower-left quadrant, Losing, is the trap waiting for the Lucky schools that have been lulled into complacency. Yesterday's suburban districts are today's urban systems. Parental support and unlimited economic resources are supplanted by families in which two parents work four jobs or, with increasing likelihood, one parent works two or three jobs. Private tutors who created the illusion of success for the Lucky schools have been displaced by a combination of electronic babysitters more intent on destroying the universe than improving math skills. Despite these obvious changes, the Losers witness a decline in results and cling to a deliberate lack of interest in the antecedents of excellence. They return from each "Innovations in Education" conference to see a school with the same schedule, the same teacher assignment policy, and the same feedback system as they have had for decades. They claim to embrace "professional learning communities," but they have merely renamed their faculty meeting. They talk a good game about "assessment for learning" but cling to a regime of final examinations that represents the opposite of that ideal. They have spent enormous sums of financial and political capital to promote "instructional leadership," but leadership time continues to be devoted disproportionately to matters of administration, discipline, and politics. At the highest level of leadership, the time devoted to the care and feeding of board members and other influential politicians far exceeds the time devoted to changing the learning opportunities for students.

The lower-right quadrant, Learning, represents a marked departure from the Losing quadrant. In this quadrant are schools that are taking risks, that are making dramatic changes in leadership, teaching, data analysis, schedule, intervention policies, and feedback systems. Teachers and administrators in these schools are doing everything that their visionary leaders have asked. They take 9th grade students who were reading on a 5th grade level and, with intensive intervention that was decidedly unpopular with students, parents, and many faculty members, moved them to the 8th grade level. Schools in this quadrant include middle schools that required double literacy periods for every single student; students reading at the 3rd grade level moved to the point of almost achieving 6th grade standards, and for the students who were already proficient, the trajectory toward high school success was improved dramatically. Teachers and leaders in these schools improved attendance and discipline and reduced failure rates. They engaged in strategies today that will dramatically reduce the dropout rate next year.

Nevertheless, their results continue to show that most students fail to meet grade-level standards. In the one-column newspaper report on year-end test scores, there appears to be little difference between the Losers and the Learners. In fact, the Losers are portrayed as victims and receive a good deal of sympathy and support from parents and staff members. The Learners, in contrast, endure the worst of both worlds—abused not only for low test scores but also for their attempts to improve student learning. "We worked harder than ever, and what do we have to show for it? Another year of missing Adequate Yearly Progress targets!"

Only the most thoughtful and nuanced school accountability system can differentiate between the Losers and the Learners, yet a growing number of systems have been able to do so. Norfolk Public Schools (Reeves, 2004a, 2006b) won the Broad Prize for Urban Education in 2005 not only because it produced great results, narrowing the achievement gap and improving performance, but also because it documented in a clear and public way the link between causes and effects, between the actions of teachers and school leaders and student results. Their experience is hardly unique (McFadden, 2009), and the preponderance of evidence for three decades has demonstrated that school leadership and teaching influence student results (Goodlad, 1984; Haycock, 1998; Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005; Reeves, 2006b). The Learning quadrant remains the Rodney Dangerfield of education: it "gets no respect" because in a society obsessed with the vertical axis of test scores, the cause data—teacher and leadership actions—remain in analytical oblivion.

The upper-right quadrant, Leading schools, represents the gold standard for education. These are the schools that not only have great student results but also possess a deep understanding of how they achieved those results. But behind every silver lining is a cloud. Today's Leaders could be tomorrow's Lucky or Losing schools. How can such a fall from grace be avoided? The answer is what my colleagues have christened the "5-minute rule," and it applies to almost every sphere of life. If you make a terrible mistake—the examples from this week's news would fill a book, and the same is true of any week in the future in which the reader considers these words—then you should feel awful about it. Engage in abject apology, self-abasement, public humiliation, pillory and post, confession and…well, we already covered the part about humiliation and apology—for about 4 minutes and 59 seconds. But after 5 minutes, quit the spectacle and get back to work. If, on the other hand, you win an international award for excellence, then call your mom, brag to your friends, and swim in the smug satisfaction of a job well done—but not for more than 4 minutes and 59 seconds. Then get back to work.

Autopsies yield interesting information, but they fail to help the patient. Similarly, educational accountability systems that focus on pathology yield limited information about how to help students whose needs are very much in the present. We must focus not only on effects but also on causes; and in the realm of education, the causes on which we can have the greatest influence are teaching and leadership. In the next chapter, we turn the microscope upside down, focusing not on the students, who are so commonly the object of our inspection, but on teachers and leaders. In particular, we consider the role of professional development strategies on student achievement.

![]()

Chapter 2

Uniform Differentiated Instruction and Other Contradictions in Staff Development

My son and I recently had lunch at a new restaurant in our town. The walls were emblazoned with claims that their french fries were "cholesterol free," a claim that sounded vaguely healthy. I could not avoid noticing, however, that not a single diner in the restaurant was munching solely on the presumably healthy fried potatoes. They accompanied their cholesterol-free side dish with an enormous hamburger, often with bacon, cheese, and fried onions. This is the sort of diet I can easily adopt. The label screams "healthy" while the reality provides full employment for another generation of cardiologists. This chapter considers a similar paradox in the field of education and explores how teachers and leaders can confront the challenges that are required for implementing high-impact professional learning.

High-Impact Professional Learning Defined

High-impact professional learning has three essential characteristics: (1) a focus on student learning, (2) rigorous measurement of adult decisions, and (3) a focus on people and practices, not programs.

First, high-impact professional learning is directly linked to student learning. The most important criterion for evaluating professional learning strategies is not their popularity, ease of adoption, or even the much vaunted imperative for buy-in from stakeholders. (In fact, change at any time is not popular, and therefore any proposed change that garners this mythological level of buy-in is not a meaningful cha...