![]()

Chapter 1

Empowering Students to Find Their Own Way

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The shift from industrialized to personalized is a global one, and it is revolutionizing medicine, journalism, music, television, publishing, politics, and self-expression. Yet in the school environment, life continues to be mostly standardized. We remain in a culture that promotes one curriculum for all, one age group and one grade at a time, and one set of tests to determine learning.

However, the fact is, the more challenging, complex, and uncertain the world becomes, the greater the need for education to transform our ways of customizing learning. We must encourage our students to become problem solvers and creative thinkers. If our students are to be successful, they will need to find work that is as satisfying to the human spirit as it is satisfying economically.

As teachers, we need to design learning experiences that help students get in touch with who they want to be and what they want to accomplish in the world. We must include opportunities for all students to build social capital and develop a voice for interaction with people in power positions. They must learn how to create and use professional networks and develop and promote their innovative ideas. Enter personalized learning.

Personalized learning is an umbrella term under which many practices fit, each designed to accelerate student learning by tailoring instruction to individuals' needs and skills as they go about fulfilling curricular requirements. We believe the scope of personalized learning, as it's presently and generally understood, must expand to allow students opportunities to explore and develop their own passions and interests. One of its aims must be to unleash the power of students' aspirations, which will strengthen their eventual participation in citizenship and the economy. As Tony Wagner and Ted Dintersmith (2015) have suggested, "The purpose of education is to engage students with their passions and growing sense of purpose, teach them critical skills needed for career and citizenship, and inspire them to do their very best to make their world better."

This purpose, however, often remains unfulfilled. Students from even the most privileged schools may suppress their aspirations—their passions and intense interests—because their deepest desires are held captive to the practicality of what others call success. Likewise, students born into poverty may suppress their aspirations because their teachers deem those aspirations impossible to achieve. The promotion of college and career readiness often creates more hurdles for students to overcome as they face the gatekeepers of their future. We believe that the way to help students build the intellectual and social strength of character that everyone needs in the contemporary world is by attending to the dispositions for continuous learning and success through personalized experiences.

In this chapter, we first describe what personalized learning truly is and can be and then turn our attention to the dispositions necessary to bring this model of schooling to life—the Habits of Mind. We show how the fusion of the two provides a framework for creating learning spaces in which students thoughtfully solve problems and invent their own ideas.

The Four Attributes of Personalized Learning

Personalized learning is a progressively student-driven model of education that empowers students to pursue aspirations, investigate problems, design solutions, chase curiosities, and create performances (Zmuda, Curtis, & Ullman, 2015). There are four defining attributes of personalized learning, each of which can be used as a filter to examine existing classroom practices or construct new ones. These are voice, co-creation, social construction, and self-discovery.

Voice

The first defining attribute is voice—the student's involvement and engagement in "the what" and "the how" of learning early in the learning process. Instead of being passengers on the curricular journey that the adults have mapped out, students are valued participants, helping to set the curricular agenda and taking the wheel themselves. Personalized learning encourages students to recognize not just the power of their own ideas but also how their ideas can shift and evolve through exposure to the ideas of others.

Co-Creation

The second attribute is co-creation. In personalized learning, students work with the teacher to develop a challenge, problem, or idea; to clarify what is being measured (learning goals); to envision the product or performance (assessment); and to outline an action plan that will result in an outcome that achieves the desired results (learning actions). Through the regular co-creation personalized learning requires, students flex and build their innovative and creative muscles.

Social Construction

The third attribute of personalized learning is social construction, meaning that students build ideas through relationships with others as they theorize and investigate in pursuit of common learning goals. As one of us has written elsewhere, "Vygotsky (1978) refers to the social construction of knowledge—the idea that people learn through dialogue, discussion, building on one another's ideas. … Teaching students to experience these processes help[s] learners to internalize and reshape, or transform, new information" (Kallick & Alcock, 2013, p. 51). There is real power in feeling that you are not alone, in the sense of camaraderie that comes from working collaboratively to effect a change, create a performance, or build a prototype. For students, the experience of individual bits of knowledge, ideas, and actions coalescing into a larger and better whole can be transformative, even magical.

Self-Discovery

The fourth defining attribute of personalized learning is self-discovery—the process of students' coming to understand themselves as learners. They reflect on the development of ideas, skill sets, knowledge, and performances, and this helps them envision what might come next as well as what they might do next, explore next, create next. Our aim is for students to become self-directed learners who know how to manage themselves in a variety of situations. By helping them learn about themselves, we help them build the capacity to make wise decisions and navigate a turbulent and rapidly changing world.

A Pause for Clarification: How Do Individualization and Differentiation Differ from Personalized Learning?

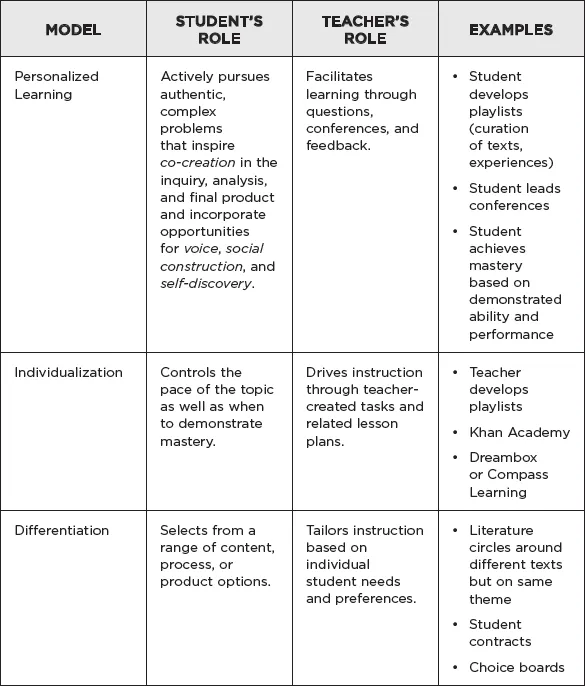

When reflecting on the four attributes of personalized learning, some readers may connect them to other instructional models often referred to as "personalized"—specifically, individualization and differentiation. Although these models are similar to personalized learning in some respects, there are meaningful distinctions, particularly concerning the nature of the tasks and the level of control students have over the learning experience. Figure 1.1 shows how the student's and teacher's roles evolve from model to model.

Figure 1.1. The Evolving Roles of Student and Teacher in Three Instructional Models

Source: From Learning Personalized: The Evolution of the Contemporary Classroom (pp. 10–11), by A. Zmuda, G. Curtis, & D. Ullman, 2015, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Copyright 2015 by Jossey-Bass. Adapted with permission.

Individualization

Individualization, as with personalized learning, allows for instructional learning to happen anytime and anyplace. The blended learning approach is a well-known application of individualization. However, in individualization students are always assigned the learning tasks, and they go on to use technology, such as computer-adapted models, a software platform, or a teacher-generated playlist, to complete those tasks. Typically, the students control the pace of their learning experience on the road to demonstrating mastery of the material. They can replay videos, do practice problems, answer questions, and receive instant feedback on their work in preparation for a computer- or teacher-generated assessment.

Individualized learning is "personalized" in that it is a way to use the efficiencies of technology to adjust the assignment and pacing to reflect the needs of the learner. There might be an emphasis on students reflecting on their learning and deepening their understanding of how they learn best. However, the relational part of the learning may be overlooked.

With a blended learning approach, students may complete some of the work independently using technology. They may co-create projects in which they apply what they are learning in an experiential environment. They may also work with a group. The significant distinction of blended learning is not how much students do off site and how much they do on site. Rather, it is about how much say the students have in the work they are doing.

A personalized learning model involves students in the design and development of the tasks they engage in. There has been much talk about technology forcing "disruption" in the schools, but in our opinion, what technology is disrupting is an exclusively compliance-driven school. This is a welcome development. Engagement is not measured by how quickly a student races through the material; it comes from how relevant, interesting, and worthy the student finds the material. This kind of engagement is built into personalized learning, as the students themselves identify or create an idea, question, or problem; determine key actions, resources, and timelines; engage in an iterative cycle of drafts; receive and reflect on feedback; and pursue next steps until the task is completed. The teacher's role is to work with students to hone skills and acquire knowledge; to give that knowledge context; and to help students ground knowledge and skill development in authentic, complex, and problem-based endeavors.

Differentiation

Differentiation embraces the reality of all the learners in the room, with their range of skills, readiness levels, and areas of interest. In this model, teachers start where the students are to create a range of learning experiences that students can be assigned to or select themselves. It's the latter form of differentiation—when students exercise choice—that can be confused with personalization, situations in which students can select the resources or topics to explore (content differentiation); how to investigate or develop an idea (process differentiation); and the form of the demonstration of learning will take (product differentiation). This differentiation encourages student choice within the confines of what the teacher has developed as viable options. The teacher is still in control of the design and management of the experience.

In comparison, a personalized learning model opens up the door for students to significantly shape what they do and how they demonstrate learning. They have a seat at the design table, the evaluation table, and the exhibition table. They have more ownership from start to finish around the development of an idea, the investigation, the analysis, the refinement, and the presentation to an authentic audience.

Readers who are familiar with project-based learning might like to see it included for comparison in Figure 1.1. However, we see project-based learning as something that is under the umbrella of personalized learning. It is part of that progression in which students move from developing their thinking as part of a teacher-designed set of choices for a project to developing a project based on an independent, personal inquiry of their own. Project-based learning always includes a challenging problem or question, sustained inquiry, authenticity, student voice and choice, reflection, critique and revision, and a public product (Larmer, Mergendoller, & Boss, 2015). These experiences can be vetted by examining them for voice, co-creation, social construction, and self-discovery—in other words, by using the four attributes of personalized learning as filters to clarify the degree to which students have opportunities to think, create, share, and discover.

The student-centered personalized learning we explore in this book is a vibrant, dynamic, messy way of learning that breaks down the walls that separate subject areas into silos, the school world from the outside world, and individual achievement from community growth. Students learn from and are influenced by the adults, peers, and experts with whom they work as they socially construct knowledge. They use what they learn about themselves as a compass to direct their choices, decisions, and active engagement.

Frankly, this is demanding work. How can teachers equip their students to meet the challenge?

Habits of Mind—A Set of Dispositions for Engagement and Learning

If we want students to reach for higher levels of thinking and performing, they must have opportunities to engage in, develop, and demonstrate a much richer set of skills and dispositions than are measured in the narrowly defined tests so prevalent today. The emphasis of most standards-based tests is measuring and reporting on academic knowledge. Although that is important, our students need to build the habits necessary to embark on projects in which the outcome is not immediately apparent. They need to develop the Habits of Mind that direct their strategic abilities and expand their resourcefulness and capacity for engaging with and solving challenging problems.

A habit is something done automatically, without too much self-awareness. Consider driving a car, for example. Although there is a certain amount of automaticity in steering, accelerating, breaking, passing, and merging once someone has learned how to drive, a driver needs mindfulness when confronted with a disruption, such as an icy road or a pothole. These environmental disruptions demand considered decisions. Likewise, students often go "on automatic," memorizing what is expected on a test. However, when they encounter a situation of uncertainty, a situation in which the answer is not immediately apparent, they need to be more considered in their thought processes. As Habits of Mind, such as thinking flexibly or questioning and problem posing, are brought to consciousness, students are able to confidently navigate the complexity of the situation. The Habits reside in that very important space in which we shift from automaticity to mindfulness.

The 16 Habits of Mind (Costa & Kallick, 2008), shown in Figure 1.2, are drawn from a modern view of intelligence that casts off traditional abilities-centered theories and replaces them with a growth mindset. These habits are often...