![]()

TIP 1

Coherent, Connected Learning Progression

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Although it appears simple—teach a coherent lesson that flows logically—proficiency in this first TIP remains elusive to many teachers in their daily instructional practice. Yet effectiveness with this TIP is crucial to help build and support success with the other TIPs.

Far too often our schools and classrooms fall into patterns that can be described by an expression used by computer programmers and technology designers: "garbage in, garbage out" ("GIGO" for short). For computer programs or apps with poorly written code (garbage in), the outcome becomes a product that is unpredictable, that crashes, or that fails to achieve the desired goals (garbage out).

For educators, a lack of clear and focused intentionality about what we do and why we do it likewise results in poor and unpredictable outcomes that often fall far from our initial goals and targets. This chapter focuses on how to establish a framework for instruction and learning that is intentional—going well beyond a mentality that is limited to simply covering topics.

Have you ever noticed how two people may hold radically different perspectives even though the conditions appear virtually the same? Nowhere is this clearer than in the variety of perspectives that teachers and leaders have about the content standards adopted by their state. In a comparative study of exemplary versus experienced teachers, exemplary teachers tended to view standards as a framework to help guide their instructional decisions (Marshall, 2008). Experienced teachers, those with 10 or more years of experience who were not rated as exemplary, tended to view standards as obstacles or barriers that must be overcome.

Thus, one group sees standards as positive and supporting effective instruction, whereas the other views standards as negative and interfering with instruction. We can debate aspects of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for mathematics or English language arts, the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), the College, Career, and Civic Life Framework for Social Studies State Standards (C3 Framework), or standards adopted by individual states, but once the debate has concluded and the standards have been selected, it is up to the district, the school, or the teacher to decide how those standards will or will not influence the teaching and learning that occur.

One thing boldly stands out when comparing the latest iterations of national standards to their predecessors: expectations have been raised for all students. As I watch teachers and school districts adopt newer standards, I find that two attitudes tend to prevail. People in one group view the standards as inherently the same as previous iterations—thus holding on to what is familiar instead of seeing what has changed. People in the other group grasp and understand the change and actively explore how they and their students can succeed within the boundaries of these newer expectations. Obviously the expectations for each discipline cannot be fully generalized to all sets of standards, but the changes evident in many of the new standards include placing greater value on the expression of higher-order thinking (e.g., evidence-based claims, modeling complex ideas and phenomena). Although some excellent teachers have been doing some of these things for years, challenging students with higher-order thinking has become the required norm, not the exception demonstrated by a few teachers in each building.

Unlike many earlier sets of standards, the newer iterations help to provide explicit links between skills and practices and among disciplines. In mathematics, this means students must now focus on mathematical practices such as modeling solutions to complex real-world problems versus simply mimicking solutions to exercises that have previously been modeled by the teacher. In science, students need to model complex phenomena and justify claims using data instead of just making observations and listing terms. In social studies, students need to situate knowledge into a civically responsible context. For language arts, reading and communicating must be grounded in evidence.

The push for tackling complex thinking and supporting claims with evidence is now prevalent in all grades and all disciplines, moving students away from accepting an idea without challenging the thinking behind it. Previously, something such as "There is no right answer" was a common teacher statement intended to encourage student participation. The new standards suggest that perhaps a better statement is "Correct answers are those with solid evidence to support the claim." Note that in all cases, students still have to achieve the lower-order skills (remember, recall, list, memorize), but now such skills are a means to an end and not the end in itself.

The quandary and seeming contradiction for some teachers becomes this: How can we expect students to succeed under more demanding standards if they have not been successful with the previous, less demanding expectations? This chapter begins to resolve this tension, but an initial response is that perhaps the higher expectations will provide the impetus and opportunity needed for change if we capitalize on the opportunity before us.

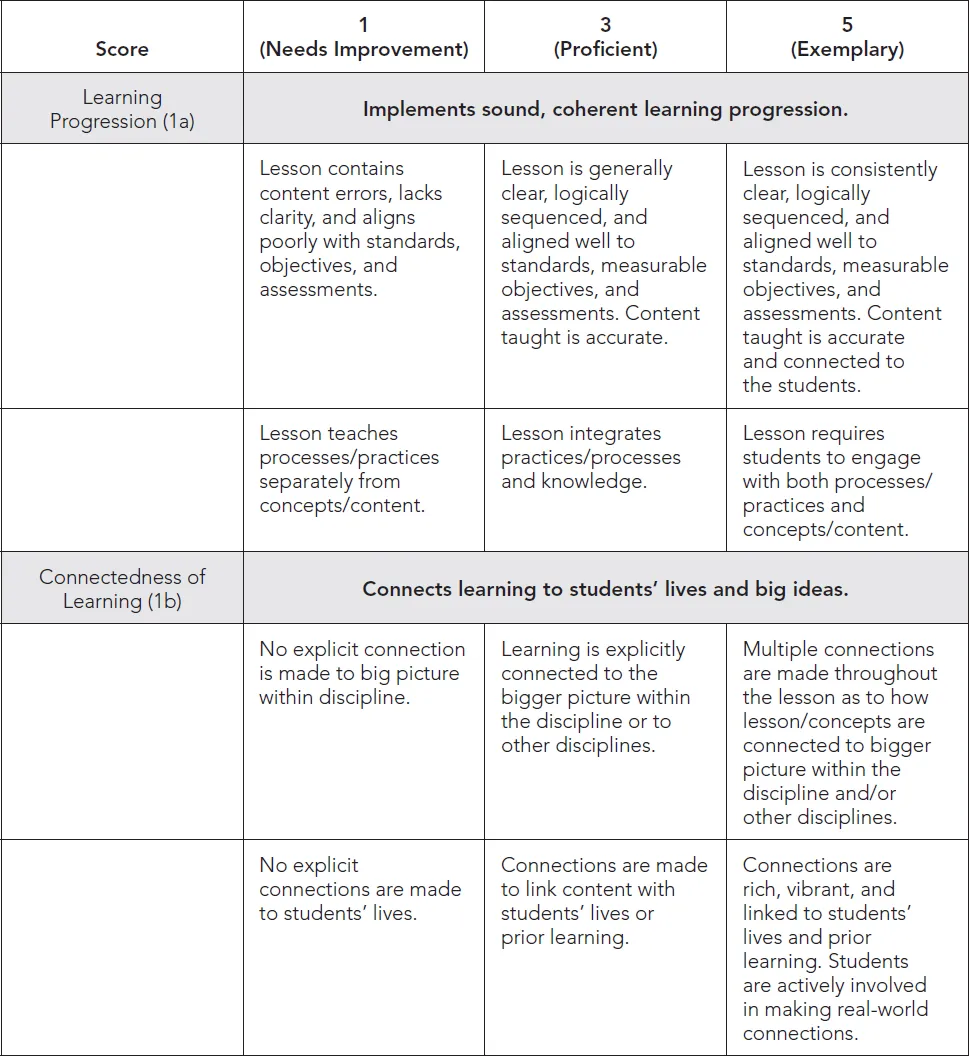

TIP 1 focuses primarily on two questions: (1) How well does your lesson provide a coherent learning progression that unites both skills and knowledge (Learning Progression), and (2) How well, and where, is your lesson connected to both the student and to the bigger picture (Connectedness of Learning)?

Learning Progression

A vast difference exists between finding and teaching one of the millions of lessons available on virtually any topic versus constructing and facilitating a learning progression that is intentional, focused, and well aligned. For proficient teaching performance, the teacher must personally demonstrate and convey accuracy in the essential knowledge and skills; the lesson must be clear and logical in its progression; and it must be well aligned to the standards, objectives, and assessments. To ensure that the most appropriate lesson is selected from the millions available, we must be intentional regarding our choices. First, we must know what we want students to know and be able to do before we go chasing lessons that just fit a given topic. Second, the lesson needs to be developmentally and intellectually appropriate for our students. Finally, we must learn to tweak new or existing lessons to fit the needs of our students and not just copy and use as the author posted—particularly when it does not fully meet the needs of our learners or our targeted objectives.

TIP 1 Coherent, Connected Learning Progression

Source: © 2015 J. C. Marshall, D. M. Alston, & J. B. Smart. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

? How do you know if your instruction is accurate?

Teachers who understand their discipline and their content frequently convey an energetic and engaging tone that goes beyond just transferring knowledge to students. For years, educators have known how important it is to provide clarity of thought and purpose during lessons and assessments, but this is often easier said than done. Lack of clarity is often evident when students continually are confused about what is being asked of them or what they are supposed to be doing. Teachers often think their questions are clear—those asked both orally during class and on written tests; but this assumption is often challenged when students either respond with blank stares or perform worse than expected on assessments. Asking students which questions on a quiz or test were the most confusing—and why—is a quick way for the teacher to discern if the content was difficult or whether the wording was confusing.

? What signs indicate that your lesson is clear, logically sequenced, and well aligned with the goals/objectives?

A lesson must be well aligned. In proficient lessons, teachers make sure that the lesson activity or focus is matched to measurable objectives and that any assessments focus almost exclusively on measuring those objectives. For instance, if the 3rd grade science standard states that students will plan and conduct an investigation, then the measurable (and gradable) component becomes the degree to which students are able to demonstrate through their experiment the phenomena being tested.

I recently observed a middle school social studies class where students were tackling the following essential question: Were Hammurabi's laws just? (I will address the quality of the essential question later, but for now, let's go with the example.) This lesson required students to analyze the laws individually and as a class to determine their purpose and their effects on society. A subsequent quiz would ask students to provide evidence to support their claims.

Regardless of the objective or standard being addressed, the goal is the degree to which each student is able to demonstrate success. So it is fine for students to work collaboratively in small groups for a large portion of the learning experience, but it is important to make sure that competencies are individually demonstrated when possible and always tightly aligned with the objectives. If "comparing" is the targeted objective, then asking students to match and list on the quiz or test for the culminating experience would fall short of achieving the goal.

Even when the curriculum is prescribed at the school or district level, teachers play a significant role in how the curriculum fits with their students and within the learning context (past, present, and future). As I discuss later (TIP 5), the questioning and interactions used to guide the lesson help determine if the lesson becomes vibrant and alive for students, or if it flounders into an unpleasant and disengaging experience.

The integration of skills and knowledge—instead of being separate instructional components taught on different days—is one of the distinguishing features of CCSS, NGSS, C3 Framework, and most of the newer state standards. Although each discipline interprets this integration of skills and knowledge a bit differently, the essence is the same. In science, each performance expectation entails a combination of scientific and engineering practices (e.g., analyzing and interpreting data), core ideas (e.g., force and motion), and cross-cutting ideas (e.g., stability and change). In mathematics, standards are divided into mathematical practices (e.g., problem solving) and content (e.g., algebra). In social studies, the C3 Framework is composed of four core areas: developing questions and planning inquiries; applying disciplinary concepts and tools; evaluating sources using evidence; and communicating conclusions and taking informed action. In English language arts, the emphasis is now on processes (e.g., reading and composition) as well as content.

? How do you integrate skills and knowledge when you and your students have previously only experienced them being taught in isolation?

Connectedness of Learning

Reading a classic novel because it is important to be well read; learning to factor a quadratic equation because it will help in solving more complex problems; memorizing facts from the Periodic Table of Elements because knowing them will help later in chemistry; or learning where the key battles of World War II occurred because geography is important—these are all common yet trite explanations for relevance that lack the element of meaningfully and explicitly engaging the learner in the lesson. Further, many times the intentionality is lacking because the teacher either does not know why the students need to study "topic X" or there is a huge chasm between learning and the game of school that needs to be bridged.

Constructing a coherent and well-aligned instructional plan requires connecting learning in several ways to prevent it from being isolated and meaningless to students. The first critical connection involves linking the learning to students' lives or to their prior knowledge. Perhaps equally important is the need to connect the learning to the bigger picture within the discipline and to other disciplines. When learning is connected to the student and to the bigger picture, it becomes purposeful and valuable to the learner. Far too often learning lacks an explicit link to either of these.

? How do you best connect the lesson to the bigger picture within the discipline and to other disciplines?

In the earlier example involving Hammurabi's laws, students were using higher-order thinking skills, but the lesson had no relevance or personal connection to the learner. Students will never come to class asking to study the justness of Hammurabi's laws, so the teacher must provide the link or bridge to create a need or value for the learner. One example could include modifying the essential question to ask, Are all laws just? The lesson could begin by engaging students in a conversation or reflection on "laws" that exist in their home or an imaginary scenario about a legislative proposal to ban rap music for all individuals under age 18. Either topic could lead to a discussion as to whether a proposed law was just, effective, or good for society. Once students are engaged in the conversation and see a personal connection to the topic, then it is possible to focus more deeply on studying the concept in context, which, in the example of Hammurabi's laws, would involve looking at other cultures and societies.

? Where do opportunities exist to connect today's lesson to your students' lives?

Actions for TIP 1

To guide your discussions, self-reflection, and next steps, consider the following actions that address the central concepts for TIP 1: Learning Progression and Connectedness of Learning.

Action: Check Your Content Knowledge to Maximize Accuracy and Clarity

Most educators have probably not had their content knowledge thoroughly checked or questioned since they took their student-teaching content exams, such as the Praxis tests. To be clear, taking a course on the topic does not guarantee solid content knowledge, nor does it ensure an ability to link the content to other concepts. So you need to seek other ways to check the accuracy of your own knowledge.

One possibility is to get together with an expert to discuss the flow, content, and connections related to an upcoming unit. This conversation may lead to ideas for connecting the content to the bigger picture and for improving your depth of knowledge. Preparing several questions ahead of time will help guide the conversation. Consider these suggestions: X is a difficult concept to teach. How would you explain it to a novice? How is your work/field connected with other fields? What is new in the field?

If conversing with an expert is not possible (or if the very idea is intimidating), another way to help ensure greater accuracy is to study common misconceptions about the concept being studied. One misconception I have heard expressed many times by elementary through high school teachers is that the blood returning to the heart is blue. This notion continues to be perpetuated in classes every day, but a little research would quickly reveal that it is not true and would explain why the misconception commonly exists among teachers and students. In some cases, studying historical contexts will reveal how stories and interpretations have changed over time—sometimes making perceptions more accurate and sometimes, like the game of gossip, making them less accurate. In mathematics, you might consider common difficulties you notice in students' solutions to problems. In English, you could revisit common writing errors, along with recent changes in conventions used in writing.

A few semesters ago, one of my student teachers asked how she could improve her confidence as a teacher relative to her content knowledge. As this conversation proceeded, it was clear that even though this student had a 3.5 grade point average in secondary science education, she was uncomfortable connecting the key concepts within her own discipline. My response was simple: read, read, read. We can never be too well read in our field; there are always new insights to glean and knowledge to acquire. As you become better read in your field, much of the information will become redundant. At that point you can simply scan the material, staying alert for new points. Keep in mind that the abundance of resources available via the Internet comes with a caveat: millions of documents—including potential lessons or activities—are instantly available, yet there is no filter to ensure quality or accuracy.

Finally, another way to improve accuracy in your lessons is to invite a peer or department chair whom you respect to sit in on one or more of your classes and provide an honest assessment of the content knowledge you have displayed. You can then ask them for suggestions for improvement, where necessary.

We have long known that the clarity of the teacher is absolutely vital to maximizing learning (National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, 2006; Rosenshine & Furst, 1971). The ability of the teacher to plan and then implement a lesson with clarity is essential. The challenge is that we often assume that because we teach something, it is clear. Thus it is impor...