![]()

Section II

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

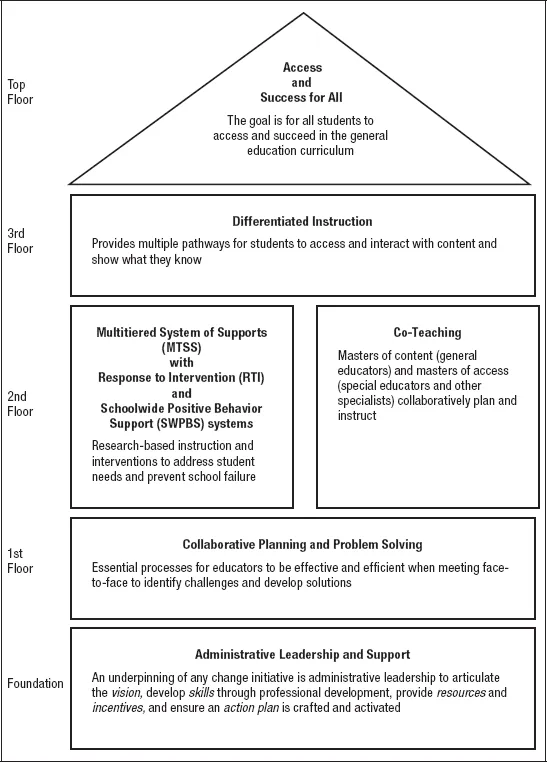

Figure II.1 displays an inclusive-school framework that we call the Schoolhouse Model (Villa & Thousand, 2011). The multistory schoolhouse framework is built upon a strong foundation of administrative support. Each subsequent floor represents one or more educational best practices or school restructuring initiatives that interrelate and build upon one another to achieve overarching goals of access to and success with the general education curriculum for every child.

Figure II.1. The Schoolhouse Model

As the figure shows, a firm foundation of administrative leadership and support underpins the processes and initiatives on the floors above. Chapter 3 examines administrative leadership and the five variables to which district and building administrators must attend in order to facilitate change and progress in any reform initiative.

The floor immediately above the schoolhouse foundation acknowledges collaborative teaming and creative problem solving as essential processes for actualizing change. In addition to administrative support, restructuring for inclusive education depends upon school and community members collaboratively developing and using skills, processes, and time to creatively identify challenges, generate and execute solutions, and track student progress. Chapter 4 examines barriers to and elements of effective collaborative teaming and offers tools for systematically activating creativity and planning effective solutions.

The second floor of the Schoolhouse Model is shared by two organizational structures and processes for marshaling and deploying human resources to increase the likelihood of curriculum differentiation for students with diverse learning profiles. The first structure, described in Chapter 5, is a Multitiered System of Supports (MTSS) for preventing school failure and avoiding special-education referral through high-quality instruction in general education. The chapter describes how the academic support side of MTSS, known as Response to Intervention (RTI), and the behavior support side, known as Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support (SWPBS) systems, work together to promote student success through three tiers of evidence-based instruction, support, and interventions.

Also on the second floor is co-teaching, another structure for deploying human resources. Introduced in Chapter 6, co-teaching is the practice of members of a school community—general and special educators, other specialized support personnel, and students themselves—sharing instructional responsibility for all students assigned to them. Co-teaching is the form of collaboration that best supports the education of diverse learners (see Figure II.2 for other forms that are more or less intensive). Chapter 6 examines four approaches to co-teaching and offers tips for more effective practice.

Figure II.2. Least to Most Intensive Collaborative Support Options

Consultative and Stop-in Support

Consultative support occurs when one or more adults, often including a special educator, meet regularly with classroom teachers to monitor student progress, assess the need to adapt or supplement materials or instruction, and problem solve as needed. Specialized professionals such as nurses, occupational and physical therapists, augmentative communication specialists, and guidance or career counselors often provide periodic consultation. Students also may seek assistance from consulting staff for general support or specific assignments.

Stop-in support occurs when consulting support providers stop by the classroom on a scheduled or unscheduled basis to observe student performance in the general education context, assess the need for any modifications to existing supports or curriculum, and talk face-to-face with the student, classroom teacher, and/or peers.

Co-Teaching Support

Co-teaching support occurs when two or more people share responsibility for teaching all of the students assigned to a classroom. There are four co-teaching approaches:

Supportive: One teacher takes the lead and others rotate among students to provide support.

Parallel: Co-teachers work with different groups of students in different areas of the classroom.

Complementary: Co-teachers do something to enhance the instruction provided by another co-teacher.

Team: Co-teachers jointly plan, simultaneously deliver, and equitably share responsibilities and leadership.

Individualized Support

Individualized support involves an adult, oftentimes a paraprofessional, providing support to one or more students at predetermined time periods during the day or week, or for most or all of the day. The key to successful individualized support is to ensure that the designated support person does not become "Velcroed" to an individual student, but, instead, (a) deliberately prompts natural peer supports, (b) supports the other students in the class, and (c) facilitates small group learning in heterogeneous groups. The goal is to phase out the need for individualized support by facilitating both increased student independence and increased natural support from classmates and teachers.

Given administrative support, tools for collaborating, and structures for deploying human resources, educators are poised to engage in the third-floor practice of differentiated instruction. Differentiated instruction provides multiple pathways for students to access content, express what they know, and derive meaning from what they are learning. Chapter 7 describes and provides examples of two approaches to differentiating instruction—a reactive "retrofit" approach and the proactive Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach.

The ultimate goal of education, represented by the top floor of the Schoolhouse Model, is access to and success in the general education curriculum for every student. Chapter 8 reminds readers of this overarching goal and offers suggestions for building a schoolhouse that welcomes, values, empowers, and supports every student's success in shared learning environments.

Finally, the second Voice of Inclusion presents the perspectives of 14 principals from exemplary inclusive schools across the nation as to how best to actualize the Schoolhouse Model.

Reference

Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (2011). RTI: Co-teaching & differentiated instruction. Port Chester, NY: National Professional Resources.

![]()

Chapter 3

The Foundation: Administrative Leadership and Support in Managing Complex Change

Richard A. Villa and Jacqueline S. Thousand

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Why is change in organizations so difficult and so often unwelcome, even when there is overwhelming evidence that the status quo isn't working? Why do expectations for achieving both excellence and equity for all children in our public schools seem beyond reach or ridiculous? Why do people in the midst of a change initiative feel confusion, anxiety, or frustration? Why is administrative leadership unclear as to where to start or what direction to take with impending best practice initiatives? Why does progress occur in some places and not in others? Why has teaching not achieved the desired results for many children and youth?

Such questions have nagged us for years as we have promoted more inclusive educational options for students with and without disabilities. Though we always knew that there existed understandable ways of leading organizational change, it was only after we had gone through and observed transformations of school cultures and practices ourselves that answers began to emerge. In this chapter, we purposely do not draw absolute conclusions about or offer prescriptions for leading change for the same reasons Margaret Wheatley articulates in her assumption-shattering book, Leadership and the New Science (2001):

I no longer believe that [school] organizations can be changed by imposing a model developed elsewhere. So little transfers to, or even inspires, those trying to work at change in their own organizations. … [T]here is no objective reality out there waiting to reveal its secrets. There are no recipes or formulae, no checklists or advice that describe "reality." There is only what we create through our engagement with others and with events. Nothing really transfers; everything is always new and different and unique to each of us. (pp. 8–9)

We believe, as Wheatley does, that "we have only just begun the process of discovering and inventing the new organizational forms" (p. 7) and paradigms of inclusive schools that are in sync with the diversity, rapid pace of change, and unpredictability of 21st-century life. As educational explorers and inventors, we must give up many, if not all, of our existing ideas of what does and doesn't work in schools. Einstein understood the difficulty long ago when he observed that it is impossible to solve complex problems with the same consciousness we use to create them.

The Five Variables for Managing Complex Change

To orchestrate change and progress in education, district- and building-level leaders, site-based leadership teams, department chairs, teacher union leadeship, and grade-level team leaders must attend to the following five variables:

- Building a vision of inclusive schooling within a community

- Developing educators' skills and confidence to be inclusive educators

- Creating meaningful incentives for people to take the risk of embarking on an inclusive schooling journey

- Reorganizing and expanding human and other resources for teaching diverse students

- Action planning devoted to strategies for motivating staff, students, and the community to become excited about the new big picture

These variables contribute to the successful management of complex change within any organization. Studying these variables offers insight into the actions that administrators and other change leaders can take to transform schools into inclusive learning communities.

Vision

According to Schlechty, one of the greatest barriers to change in schools is the lack of a "clear and compelling set of beliefs regarding the direction of the schools and a vision of the schools that these beliefs suggest" (2009, p. 195). Building a vision, or visionizing, is the first variable to consider when formulating change. Unless we devote time and effort to building a common vision, many in the school and greater community may remain uncertain about the wisdom of promoting inclusion.

We like the term visionizing (Parnes, 1992a, 1992b) because we think an action verb suggests the active mental struggle and the "mental journey from the known to the unknown" (Hickman & Silva, 1984, p. 151) that people go through when they reconceptualize their beliefs and declare public ownership of a new view. Visionizing involves creating and communicating a compelling picture of a desired future and inducing others' commitment to that future.

Leaders of inclusive schools stress the importance of clarifying for themselves, school personnel, and the community a vision based on three basic assumptions:

- That all children are capable of learning,

- That all children have a right to an education alongside their peers, and

- That the school system is responsible for attempting to address the unique needs of all children in the community.

To articulate a vision of inclusion is necessary, but it is not sufficient. The vision must also be adopted and embraced. Visionizing requires us to foster widespread understanding and consensus about the vision, which we can do by implementing the strategies that follow.

Examining Rationales for Change

One strategy for building consensus is to educate people about the theoretical, ethical, legal, and data-based rationales for inclusive education. Recall the end of Chapter 2, where we asked the following two questions:

- Personally and professionally, which of the rationales are the most compelling to you? That is, which are most likely to lead you to support a unified, inclusive educational system of general and special education?

- Which of the rationales do you think your colleagues, supervisors, students, community members, and policymakers find most compelling?

Your answers to these two questions are vitally important to visionizing. Our experience tells us that to build consensus, different people find different rationales to be compelling—and each rationale is compelling to someone. Norm Kunc (personal communication, November 20, 2015) suggests that we picture each person as a circle with two halves: one half comprises concerns about a proposed change, and the other half comprises beliefs, both supportive or nonsupportive, about it. He further suggests that to shift people's beliefs in favor of change, we must first listen to and identify their concerns (i.e., questions, fears, nightmares, confusions) about the change. Next, we must use this information to determine which rationales "speak to" each individual's priority concerns. For example, fiscal and legal rationales may speak to administrators and sch...