![]()

Part 1

Goals

![]()

Chapter 1

Student Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Literacy is a big part of the everyday world of adolescents. They pass notes, read e-mail, write in journals, share stories, study the driver's manual, decipher train schedules, search the Web, send instant messages to one another, read reviews of video games, discuss movies, post blogs, participate in poetry jams, read magazines and novels, and so much more. Yet many middle and high school teachers and administrators lament that students just do not read and write anymore, often blaming today's TV and video game culture.

We maintain that many, perhaps most, teenagers are actually highly motivated readers and writers—just not in school. For school leaders who want to improve the academic literacy skills of students so that they will be more successful in school, this situation poses a challenge. Addressing this challenge is the key to a literacy improvement initiative. Helpful questions for school leaders to ask include the following:

- What evidence do we have of students' out-of-school literacy skills that we can build upon to encourage completion of reading and writing assignments in school?

- What motivates and engages students to read and write, and how can we include these types of opportunities throughout the school day and across the content areas?

- What kinds of coaching, instruction, and practice develop proficiency in reading and writing, and how can leaders support teachers to provide these?

Many researchers have explored the richness, competence, and depth of adolescents' out-of-school literacies (see for example, Alvermann, 2003, 2004; Lee, 2005; Smith & Wilhelm, 2002). The motivation for students to read and write outside of school seems to be threefold: (1) the topic needs to be something they feel is important to communicate about; (2) the topic needs to be something they feel strongly about or are interested in; or (3) the reading or writing needs to take place when they want to do it, or "just in time." Add to this a feeling of competence with the language, topic, or genre and multiple authentic opportunities for feedback and practice. These conditions produce situations in which adolescents are highly engaged with reading and writing.

Consider, for example, this instant message (IM) conversation between two teens who rarely read or write in school. Note the participants' high level of fluency with a code that many adults do not understand:

JZ: what's the 411 on tonight

LilK: we r abt2 hit the mall

JZ: which 1

LilK: TM

JZ: now?

LilK: yeah—going 2 get som p-za n then p/u a movie. u coming?

JZ: may-b. which movie?

LilK: dky—there r a few dope ones. what do you want 2 c

JZ: idk

LilK: what about wolfcreek

JZ: str8 J y? that what you want

LilK: j/c

JZ: what time? Go alap

LilK: Y

JZ: bcoz got 2 do some family stuff. hit my numbers b4 u go

LilK: a-rite

JZ: g2g

LilK: k

JZ: cul8r

LilK: c ya

If adolescents have reading and writing skills as we claim, why is it so difficult to get many of them to read a chapter in the history text or finish a short story in a literature anthology? Several issues are at play. First, out-of-school literacy skills may not be adequate for, or easily transferable to, academic reading and writing tasks. Second, many teachers do not build upon or bridge from out-of-school literacies to develop academic literacy skills because they may assume that because students will not read and write that they cannot. Third, most academic reading and writing assignments are not particularly motivating or engaging. And fourth, many middle and high school teachers do not have the expertise to provide reading and writing instruction in the content areas.

Many students approach assignments as something to get through without understanding the relevance of those assignments to their lives. Many try to avoid assigned reading because for them reading is an unpleasant, arduous, and unrewarding task; for some middle and high school students, their decoding and basic fluency skills are too limited to read grade-level textbooks. For far more students, the content of the textbook, article, or trade book is too difficult or too irrelevant to their experience, and encountering the information on the page is not sufficient for understanding. These students need to talk, write, and connect the content to what they already know to make sense of the material on the page. Other students do not see the relevance of the assigned reading to their lives and are not interested in putting forth the effort to complete the task. Often, however, many of these same students are able to persevere with difficult reading if they are interested in the subject at hand and if they get appropriate help—that is, if they can be motivated and supported to engage with the task.

Engagement with learning is essential, because it is engagement that leads to sustained interaction and practice. Coaching, instruction, and feedback become critical to ensure that students develop good habits and increase their proficiency. Increased competence typically leads to motivation to engage further, generating a cycle of engagement and developing competence that supports improved student achievement.

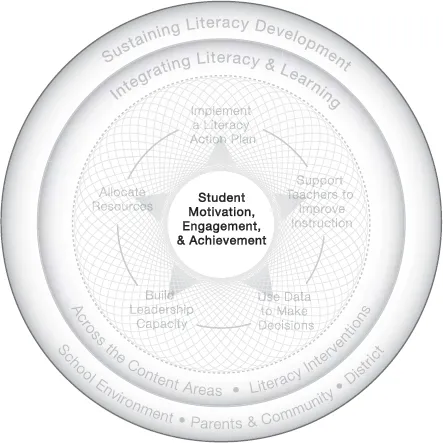

In the Leadership Model for Improving Adolescent Literacy, the interconnected elements of Student Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement make up the central goal of a schoolwide literacy improvement effort and are represented as the center circle on the graphic that depicts the model. In this chapter, we describe the well-researched connections between motivation, engagement, and achievement. Then we present strategies for motivating students to engage with literacy tasks, followed by a discussion of how engagement is connected to development of proficiency and what leaders can do to promote student motivation, engagement, and achievement. Two vignettes illustrate aspects of motivation and engagement, first through relationship building, then through instructional context. In both, the classroom itself is used as an intervention to get disengaged students motivated and involved in reading and writing for authentic purposes. We conclude the chapter with key messages.

Why Motivation and Engagement Are Important

Until recently, most middle and high schools in the United States have not included a focus on improving academic literacy skills—reading, writing, speaking, listening, and thinking—as a primary educational role. People have largely assumed that students are supposed to arrive in middle and high schools with adequate reading and writing skills that they can then apply to assignments involving increasingly complex reading and writing tasks. If, by chance, students do not arrive with these skills, educators sometimes prescribe remediation. More often, students are able to get through classes without reading and writing much at all. Well-meaning teachers may focus on alternate methods—showing and telling as opposed to reading and writing—to ensure that students are "fed" the content and not "penalized" for having low literacy skills. The result is that the students with the weakest skills often get the least amount of practice.

Other teachers assign reading and writing tasks and give low or failing marks to students who do not complete the assignments, assuming that motivation, not ability, determines if the work is turned in. The mindset of many teachers and administrators is that if students do not have the requisite reading and writing skills by middle or high school, it is simply too late. A number of educators speculate that some students just do not like to read and write—"that's just the way it is." Additionally, many middle and high school teachers do not know how to provide explicit reading and writing instruction. Specific literacy instruction, as part of content-area learning, tutoring services, learning centers, or study skill classes, has been virtually unknown in many middle and high schools.

For students with poor academic literacy skills, this lack of embedded and explicit literacy support results in a downward spiral that can lead to academic failure. It is especially important to motivate students who arrive in middle and high school classrooms with a history of failure as readers or writers. People are understandably reluctant to persist at behaviors that they do not enjoy or that make them feel incompetent—adolescents even more so. Adolescents with poor literacy skills will sometimes go to great lengths to hide their deficiency; some of them devote considerable energy to "passing" or to distracting attention from their struggles, and the effort required is a major reason why many drop out of school.

Yet discussions with teens who are struggling readers and writers do not suggest convictions such as "we are proud of not being able to read and write well" and "we should be left alone to reap the lifelong consequences of leaving school with inadequate literacy skills to face the workplace and the responsibilities of citizenship." Many of these students understand that poor literacy skills place them at a distinct disadvantage economically, personally, vocationally, and politically. They want to be better readers and writers, but in addition to their weak literacy skills, other serious barriers interfere, such as

- minimal and often inappropriate help,

- alienation from uncomfortable school environments and curricula that seem irrelevant to their lives, and

- unreceptive environments for admitting the level of vulnerability they feel.

Motivation and engagement do not constitute a "warm and fuzzy" extra component of efforts to improve literacy. These interrelated elements are a primary vehicle for improving literacy. Until middle and high school educators work strenuously to address all of the barriers, and thereby motivate students to become engaged with literacy and learning, in the words of one student we interviewed, "I can tell you it just ain't gonna happen, you see what I'm sayin'?"

The Connection Between Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement

By the time students reach middle and high school, many of them have a view of themselves as people who do not read and write, at least in school. It is often difficult for teachers to know if middle school and high school students cannot or will not do the assignments; often all they know is that students do not do them. Herein lies the challenge for teachers and administrators: how to motivate middle and high school students to read and write so that they engage in literacy tasks and are willing to accept instruction and take advantage of opportunities to practice and accept feedback, thereby improving their academic literacy skills that will, in turn, improve their content-area learning and achievement.

This is not an either/or proposition. Instruction without attention to motivation is useless, especially in the case of students who are reluctant to read and write in the first place. As Kamil (2003) points out, "Motivation and engagement are critical for adolescent readers. If students are not motivated to read, research shows that they will simply not benefit from reading instruction" (p. 8). In other words, adolescents will take on the task of learning how to read (or write) better only if they have sufficiently compelling reasons for doing so.

Because motivation leads to engagement, motivation is where teachers need to begin. Reading and writing, just like anything else, require an investment by the learner to improve. As humans, we are motivated to engage when we are interested or have real purpose for doing so. So motivation to engage is the first step on the road to improving literacy habits and skills. Understanding adolescents' needs for choice, autonomy, purpose, voice, competence, encouragement, and acceptance can provide insight into some of the conditions needed to get students involved with academic literacy tasks. Most successful teachers of adolescents understand that meeting these needs is important when developing good working relationships with their students. However, many teachers have not thought of these needs in relation to their potential consequences for literacy development, that is, to what extent they meet these needs in the classroom through the academic literacy tasks they assign and the literacy expectations they have for students.

Motivating students is important—without it, teachers have no point of entry. But it is engagement that is critical, because the level of engagement over time is the vehicle through which classroom instruction influences student outcomes. For example, engagement with reading is directly related to reading achievement (Guthrie, 2001; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Engagement—with sports, hobbies, work, or reading—results in opportunities to practice. Practice provides the opportunity to build skills and gain confidence.

However, practicing without feedback and coaching often leads to poor habits. Coaching—or, in this case, explicit teaching—helps refine practice, generates feedback, creates structured exercises targeted to specific needs, and provides encouragement and direction through a partnership with the learner. Note that more modeling, structure, and encouragement are often needed to engage students who are motivated to begin but who have weaker skills and therefore may not have the ability or stamina to complete tasks on their own.

Sustained engagement, therefore, often depends on good instruction. Good instruction develops and refines important literacy habits and skills such as the abilities to read strategically, to communicate clearly in writing or during a presentation, and to think critically about content. Gaining these improved skills leads to increased confidence and competence. Greater confidence motivates students to engage with and successfully complete increasingly complex content-area reading and writing tasks, and this positive experience leads to improved student learning and achievement.

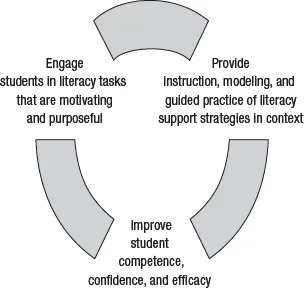

Thus, teachers have two primary issues to contend with when trying to improve the literacy skills of unmotivated struggling readers and writers: (1) getting them to engage with academic literacy tasks, and (2) teaching them how to complete academic literacy tasks successfully. Proficiency is developed through a cycle of engagement and instruction (Guthrie & Wigfield, 1997; Roe, 2001). Figure 1.1 shows a Literacy Engagement and Instruction Cycle that exemplifies the interrelatedness of teaching and learning within the context of literacy.

Figure 1.1. The Literacy Engagement and Instruction Cycle

Source: From The Literacy Engagement and Instruction Cycle, by J. Meltzer, 2006. Copyright 2006, Public Consulting Group, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

This cycle represents the learning conditions and support required for literacy learning to take place. Teachers and administrators who understand what this cycle looks like within the content-focused classroom can support the activation and maintenance of the cycle for all students. The vignettes in the next two sections of this chapter illustrate how teachers can make this happen and what types of learning environments are effective for motivating students to engage with academic literacy tasks. For leaders, the challenge is how to support teachers to develop these types of classroom experiences and contexts so that they become typical practice, rather than the exception.

Breaking the Cycle of Failure

Breaking the cycle of failure for struggling readers and writers and engaging all students to participate actively in their own literacy development requires the use of classroom environments themselves as interventions. In some cases, it is the classroom culture that prompts or supports reluctant readers and writers to want to engage with literacy tasks, resulting in their being more open to instruction. Such classroom environments provide motivation to read, multiple opportunities and authentic reasons to engage with text, and safe ways to participate, take risks, and make mistakes. In these classrooms, students feel that the teacher really cares about them and their learning. The following vignette illustrates how this type of classroom context worked to encourage the literacy and learning of one student.

Carly arrived at high school reading at the 5th-grade level. During middle school, she got involved with a rough crowd that did not care much about doing schoolwork, and figured that no one cared much anyway, so why should she try? She used to like books about real people and stories that the teachers in elementary school read aloud. In elementary school, she had been a pretty good student.

During the first week of 9th grade, Carly's English teacher told her that she would like Carly to join the mentoring club. Carly told her, "No disrespect, but I don't think so." The teacher, Ms. Warren, persisted. Furthermore, she read all of Carly's papers, checked in with her daily, and had a frank talk with Carly about how she had a lot of potential, was very smart, and needed to get her reading and writing up to speed.

The books and short readings that Ms. Warren assigned in English were interesting and relevant to Carly, describing real events and people with dilemmas, but they were hard for her to read. Students in Ms. Warren's class were encouraged to share their opinions and ideas—but they always had to back them up with what they had read in the text. Ms. Warren taught her students multiple strategies for approaching different types of texts and always connected what they were reading to important themes in students' lives—power, cheating, love, violence. Carly tried the strategies and found they helped a lot.

Carly began to work hard—but just in that one class. She agreed to join the mentoring club because Ms. Warren just wore her down and kept asking her again and again. To her surprise, Carly found she loved tutoring younger students, and the experience made her work harder on her own reading and writing ...