![]()

Part One

Why We Teach: Relevant Concepts

The little town that time forgot, that the decades cannot improve.

—Garrison Keillor

![]()

Chapter 1

Inspire Your Students

Great men are they that see that spiritual is stronger than any material force, that thoughts rule the world.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Why do we teach? Certainly we teach to inform, but we must also teach to inspire. Most of us want to change a learner's life for the better. Finding confidence through the study of a subject makes a life better. Doing well on an exam is an important part of life. Learners are more than a sponge for academic content, and they are more than a test score. Holism in our goal setting is vital, and thinking collectively is helpful in the complex profession we call teaching. Complex is the descriptor because people are complex and, hence, learning itself is complex. If learning were as simple as adding to a knowledge storehouse in the brain, we could just sit our students in front of computers 100 percent of the time and dismiss all teachers.

Our rapidly changing global culture makes the search for pedagogical authority more elusive than ever. U.S. education, which is historically and politically embedded in our ideal of a better life, is fragmented as never before. The conjunction or holds sway in our thinking, as when we think we must stop enriching teaching as we teach basic skills, or as we focus only on achievement to the demise of considering students' unique aspirations. But we do not have to choose between who we teach and what we teach. We can do both even as we prioritize the who in education: our students.

We propose a return to schooling where education begins with learners and their transformation, where the teacher-student dynamic is spotlighted, where the academic and the social are meant to be connected and combined, and where the social is once again joined with spiritual meaning and transcendence.

Judy was working with her 6th grade students on "The Baboon's Umbrella," a fable from Arnold Lobel's 1980 classic children's book, Fables. Simple, but laden with profound meaning, this story is about Baboon holding open an umbrella on a sunny day, complaining that his umbrella is stuck. His friend, Gibbon, advises him to cut some holes in the umbrella so that the sun will shine through. After Baboon does so, rain begins to pour, soaking him to the skin. Lobel's moral (p. 12) is "Advice from friends is like the weather. Some of it good; some of it bad."

When Judy asked her learners what they thought of the story, Anika raised her hand and said, "My moral would be 'Do your own thinking.'" Judy asked her to elaborate, and she said, "It is silly to let your friends think for you. We might as well be baboons to do that, even though some of my friends have some good ideas." The story inspired Anika to think through an important concept, one with dimensions deeper and broader than the intellect.

Inspiring students does not require stories with morals, but we think it requires teachers who can think beyond single goal structures. Transformational teaching goes beyond the academic into the other great goal of education: socialization. In the realm of socialization goals, however, the meaning of social has splintered, separating it unintentionally or deliberately from spiritual illumination. We assert that the dynamic found between teachers and learners can have a sacred quality, and that these human relationships depend upon connections that are indeed spiritual in essence.

Students need teachers they can believe in: teachers who model lives of empathy and service. Social and spiritual goals should be aimed toward the same end: serving something or someone greater than ourselves. Emerson said that "our chief want is someone who will inspire us to be what we could be." Being what we can be reflects the potential of the human spirit. To capture the emotions and ignite the interest of learners has not only academic but social and spiritual contexts.

The Transformational Pedagogy Model

If we believe that teaching is a mere imparting of information, we have surely aimed too low. To hit the bull's-eye, we need to aim above the target of academic achievement. Learners need teachers who will, as Aristotle remarked, show them the good. The Greek educator used the term arête to describe virtue modeled by a good person. Arête represents a combination of skill, wisdom, power, and passion for good (Willard, 1998). Teachers need to be encouraged and affirmed in their roles, in their potential for transforming lives, and in their calling to the real needs of learners. That learners need teachers to guide them in their learning is a cognitive principle with affective underpinnings.

Expert teachers know the structure of their academic discipline, and novice learners need their guidance in grasping it. But learners also need the authority of sensitive mentoring as they struggle with overcoming conceptual barriers within the discipline and within their own experiences. "Who has influenced your life the most?" is an important question for both students and teachers. How students feel in a classroom may be, in the long view, more important than what they know. By envisioning pedagogy as meeting the needs of the whole person, by perceiving education as both heart and science, and by believing that teaching is about helping students find self-fulfillment through enriching knowledge, the holism and depth of learning can be embraced.

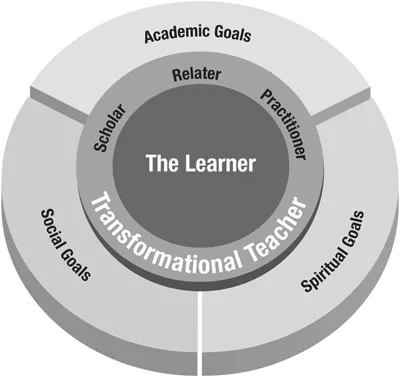

The Transformational Pedagogy Model is designed to demonstrate that holism in education can have a transformational quality. Figure 1.1 illustrates the relationship between the learner and three categories of educational goals. We define transformational pedagogy as an act of teaching designed to change the learner academically, socially, and spiritually. Transformational teaching begins with the learner, and transformational learning involves deep understanding and occurs in classrooms where teachers have high expectations. The principle is that raising student achievement is the floor, not the ceiling. Higher achievement is a by-product of teaching to a holism of goals and to a depth of understanding. We can reach the whole child through inspiration and a more reflective perception of our role as educators.

Figure 1.1. Transformational Pedagogy Model

We must look for transformational opportunities. Teachers know, for example, that assessment is not an isolated entity but is a part of the fabric of instruction. Teachers evaluate their students both formatively and summatively, but most learning takes place formatively (i.e., along the way). Students need teachers who communicate that they believe in students and all their potential. Overemphasis on summative assessment can discourage learners, but, in fact, any assessment that is less than sensitive to learning needs is misplaced in schools. For example, Rick Stiggins (2007) argues that the assessment process can lend itself to reclaiming student-centered instruction: "Even the most valid and reliable assessment cannot be regarded as high quality if it causes a student to give up" (p. 25). Transformational teaching includes a concern for a person's ultimate welfare and potential, for teaching students as well as subjects. This means that the way teachers think and learners feel in school transcends the curriculum. Students' feelings are a response to what the school or the teacher has done to satisfy or fulfill their needs as unique individuals.

* * The Power of Touch

Marian Diamond and her associates, pioneers in brain research, tell an interesting story based on "rat experiments" they were doing along with some counterparts in Japan. They noticed that in the two controlled environments geographically separated, with all other variables held constant, the "Japanese rats" lived longer than the "American rats." After further careful differentiation, they discovered a saliently important difference between the two environments. When American rats had their cages cleaned, they were allowed to simply climb into another cage. When the rats in Japan were given clean cages, they were briefly held by the research assistants before transfer. The human touch created a longer life span! Students need the therapeutic power of a transformational teacher who "touches" and transforms lives.

Teachers' feelings are vital, too, because they sustain teachers' dedication to their calling and affect those involved directly and indirectly in schools. The calling to be a teacher involves placing the whole learner at the center of teaching. Schools are only as effective as their teachers, the best of whom require and inspire many dimensions of support. As many experienced teachers know, students and teachers should expect education to be a mutually transforming experience. To teach is to be changed, as much as or even more than the learner is changed. To transform is to effect change. Transform is an "action" word. The goal is to make teaching a "trans-action," to conceive of teaching as an action across the teacher-learner gap. And, within this transaction, a transformation can take place. How can teachers teach in the holistic way demanded by the Transformational Pedagogy Model?

Using a holistic approach to teaching does not require a formula learned in teacher education courses. Instead, holistic education comes from a relationship built by sensitive teachers using pedagogy attuned to the academic, social, and spiritual needs of learners. In 2009, Roslyn taught a lesson focused on a celebration of the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's 200th birthday. Mandy, an 11th grade African American student, asked what the Emancipation Proclamation really meant: "Did it mean freedom for black people in America?" Roslyn answered the question with a question: "Mandy, what does freedom mean to you?" Her student's answer was "It means having choices and opportunities like everyone else." To which Roslyn said, "I think the answer to your question is that it was a beginning of a difficult process, but it was a new beginning." Then, Roslyn asked, "Has there ever been a time when you felt like you were given a new beginning?" This question inspired a deep discussion in the class, centered not just on the intellectual understandings from Lincoln's crisis leadership but also on deeper, even spiritual implications for students' lives. This teacher's evaluative questions are holistic pedagogy attuned to deep understanding of students' needs.

* * Emotions Affect Learning

Why are student and teacher feelings important for educational success? Neurobiological studies are confirming what teachers have known for a long time: We remember what we feel. Where were you September 11, 2001? Where were you when Barack Obama was inaugurated? What do you remember about the day? Chances are that certain memories are vivid. Learning and memory formation are prompted by episodes, places, and our emotional reactions. Emotion often motivates us to learn all we can about a topic, prompting an insatiable curiosity to explore all the issues and events that follow an important situation in our lives. We learn best through this "episodic memory" because our total being is challenged and engaged. We are holistic learners.

Pedagogy is the art and science of instruction; the term is derived from the Roman term pedagogues, educated Greek slaves who escorted Roman children to school. Pedagogy, in a strict sense, relates to how we teach. Pedagogy involves many sensitive decisions, such as when and how to apply understanding of many different teaching strategies to various educational situations. Implicit in this decision-making process is the concept of responsibility for our choices, especially those that affect others. Moral concern for the learner is implicit in the calling of teaching.

Moral concern for our students begins with building respectful relationships. As Ruby Payne (2008) has found, the verbal and nonverbal signals a teacher transmits are a vital part of showing respect for students. Interactions between teachers and students living in poverty, for example, can include greeting them with "Hi" and calling students by name, smiling, using eye contact, answering questions, talking respectfully instead of judgmentally, and helping those who need help. Everyday behaviors communicate simple respect. Establishing mutual respect can be transformational.

Transformational pedagogy integrates teaching the whole learner, rather than attending separately to academic, social, and spiritual goals. These three goals are united, even synergistic, when we pay close attention to whom we teach and why we teach. A more holistic ethic seeks to understand education in all its complexity and in all its dimensions. Miller (1997) says that holistic education is "based on the premise that each person finds identity, meaning and purpose in life through connections to the community, to the natural world, and to spiritual values such as compassion and peace" (p. 1). How can teachers transform learners academically, socially, and spiritually? Being mindful of and wise about education's purposes is a beginning.

Reflecting on Purpose

Self-fulfillment is a liberating part of education, perhaps the most important purpose of education. As teachers we want our students to be successful, but we must be careful not to narrow the meaning of the concept. Pedagogy can make the difference in education, especially if pedagogy is guided by not just the questions "How?" and "What?" but also the questions "Why?" and "Who?" Teaching can be linked to domains of knowledge and the science of learning, and teaching can be viewed as holistic. The message is that we as teachers can attain these lofty goals if we have the will to seek them.

Nathaniel is a middle-grade student who just knew he could not read. After years of failure, he had stored up enough emotional roadblocks to give up the effort. Then he met his 6th grade teacher, Iretta. She pulled him aside, looked him in the eyes, and promised him that this year would change his life. Together they would succeed. She knew Nathaniel had the desire to be a reader, even though he acted otherwise. Iretta built on that desire, helping him succeed little by little, working together until he could read independently. It was not so much what she did that made the difference; it was who she was in the relationship with the learner. Iretta's belief in Nathaniel changed his life.

It seems likely that the reader will notice the spiritual goal category of the Transformational Pedagogy Model first. We recognize the risk in including it in the model. For some who read this book, it is an automatic road block. For many educators it may conjure images of soft education, yet another form of coddling students. For others it may engender distrust for hidden agendas of religious dogma and public school lawsuits. Laura Rendon (2009) reflects on the spiritual concept as being potentially divisive: "Some individuals may be pro-religion and antispirituality. Some may consider themselves spiritual but not religious. Others view spirituality in conflict with Judeo-Christian values" (p. 27). Divisive or not, we think people are spiritual beings in their essence. The simplest acts of teaching and the well-chosen words of a teacher, such as those spoken by Iretta, constitute spiritual action. She saw Nathaniel's frustration from repeated failure, helped him persist until he succeeded in reading, and helped him transform his life.

A concern for issues that affect the human spirit is an integral part of a teacher's calling. Teachers with courage to believe they can connect to the transcendent can realize goals beyond the academic and even the social. Teachers who contribute to encouraging students to desire lives of fulfillment meet a most worthy teaching goal. Why should we consider spiritual goals as an integral part of teaching and learning? The simple answer is the relationship formed between Iretta and Nathaniel. Motivation and hope are part of the spiritual goal dimension.

Without the spiritual component, human beings are machinelike with a wondrous compilation of bones, organs, and senses (Sire, 2004). The rationalist chooses to reject the spiritual altogether. Though we know spiritual transformation as a goal and a process will not be accepted universally, we believe it is a crucial element forming the foundation of transformational pedagogy.

For our purposes we choose simplicity: Transformation is an illuminating change in head and heart that helps learners achieve their potential and their purpose. Head refers to our human capacity to discover and problem-solve. Heart is an ancient concept used synonymously with a person's essence or soul. Head and heart work together to animate who we are. Who we are is what poet Stanley Kunitz calls our "indestructible essence" (Braham, 2006). Teachers are called to activate the spiritual essence in every learner.

The Teacher-Student Dynamic

Many of us believe that schools exist to transform individuals by teaching societal knowledge and values and to transform society by being an institution for social reform. That's the larger context of schooling. In this book, we focus more on the personal, teacher-student dynamic. We believe that the Information Age exacerbates human tendencies to prioritize the larger education goals, and to minimize, and thus deprioritize, attention to the importance of the individual teacher and learner. Educators and policymakers tend to spend a lot of time at the system or policy level and forget about individual students and the creative abilities of those who teach them. Knowledge in the informational culture that our students inhabit is changing quickly, making it more important for teachers to connect curriculum to their learners' lives.

One example of the tendency to focus on the larger context of educational goals (Hood, 2009) is the trend to departmentalize instruction at younger levels. Some schools, in their desire to use subject specialists, are requiring 6-year-old elementary students to change classrooms and teachers during the school day. Having more than one teacher for young children is not necessarily a bad thing. From our holistic perspective, this early departmentalization trend prioritizes school systems' efforts to raise test scores over the more commanding priority of the sociospiritual well-being of children. Schools have no solid evidence that specialists improve young children's achievement scores, yet much like ability-grouping practices of old, we jump to conclusions based on thinking that having teachers focusing on fewer subjects is a logical way of meeting achievement test goals. We think, however, that schools and especially teachers must focus on holistic, family-style support systems as a priority. Transformational teaching places learners' total academic, social, and spiritual welfare at the center of our philosophy of teaching.

* * Horizontal Versus Vertical Grouping

Horace Mann, the father of U.S. public education, adopted our school model from Prussia. The horizontal grouping of ages replaced the vertical grouping of the one-room schoolhouse. Teachers were to become grade specialists, with the reasoning that by placing like-age groups together, teachers could be much more efficient. Unfortunately, this efficiency sometimes fails us, like when we become convinced that everyone can be taught the same lesson if they are the same age. With every year the gaps grow wider in students' reading levels. Or, if we can just group people together with similar test scores (ability grouping), much more learning will ensue. No, scores do not significantly change for the better, and self-esteem issues abound. In contrast, vertical grouping (having students of different ages work togethe...