![]()

Chapter 1

Developing Curriculum Leadership and Design

Do what you always do, get what you always get.

—Source unknown

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ann had just completed a long, arduous revision process for a science curriculum, and she was feeling the satisfaction of a job well done. She had worked with a diligent, broad-based committee of educators for three years. Their hard work was evident by the shiny, new curriculum guides that were placed gingerly on the shelves of classrooms across the district. As Ann walked through classrooms and talked with principals and teachers regarding the new curriculum, she observed, much to her surprise, that little had changed in regard to science instruction, especially in scientific inquiry. Teachers were teaching many isolated activities, but they were not engaged in the process. Ann had spent hours with the team reviewing state and national standards and discussing their implications. The team engaged in an in-depth analysis of the district data and identified the strengths and weaknesses of the current curriculum. Surveys were distributed to parents, teachers, staff, and students requesting their feedback on the science curriculum. So, why had nothing changed?

The status quo was maintained in this district because the curriculum team didn't have any discussions on the best instructional practices. Ann had assumed that the team members already had a solid foundation on these practices, so they jumped right into writing the curriculum. In her haste to get the guides produced, she made a critical error. By not reading, reflecting on, and discussing the best instructional practices, the curriculum team was not equipped to develop a curriculum that would result in long-lasting changes in instruction and student achievement.

When we hear the phrase "the good old days," it is usually uttered with a sense of longing and a fondness for a return to the way things used to be. When it comes to curriculum development, this sentiment would not hold true for many teachers and administrators who have been involved in writing curriculum over the last 10 years. In the old days, curriculum development started with a basic question: "What do we want our students to know?" Fortunately, the question of what to teach has been addressed through state and national standards. But now that state and national standards are tied to accountability measures, the questions needed to develop curriculum have changed. Federal and state leaders have spent large amounts of time and energy painstakingly identifying what and when students should learn something. Now that they have taken care of these concerns, we can shift our focus. Rather than lament what might feel like a loss of autonomy or local control, we feel that this guidance from the federal and state level can help curriculum departments move into an important new era. This new era will allow us to spend more time focusing on aligning curriculum and instruction, rather than developing curriculum guides. We have shifted from focusing on what to focusing on how.

Aligning Curriculum and Instruction

A few years ago there was a story about several new homes that were literally sliding down the slope where they had been built. These homes were well-designed, luxurious, and located in an exclusive subdivision; however, they were built on land that was slowly eroding. Because these homes were not built on a solid foundation, their design and craftsmanship were rendered useless; the houses could not be occupied. Building a home that will stand the test of time requires both a solid foundation and a sound design plan. It is not an either/or proposition. The same holds true for curriculum and instruction.

Too many times we have entered classrooms and observed teachers using research-based strategies on insignificant content. An effective instructional practice loses effectiveness if the curriculum isn't strong enough. For example, using the Four Square Writing Method (Gould & Gould, 1999) will not help improve students' writing if we ask students to write on contrived, inane topics such as how it feels to be a puddle in springtime. Even though the Four Square method is an effective strategy, this process is lost on students if they aren't asked to write as a response to reading and thinking.

Conversely, having high academic standards isn't enough if they are not implemented through powerful instructional methods. Unfortunately, many of us have spent time writing guides that outlined great standards only to have them sit on the shelf while classroom instruction remains unchanged. Curriculum and instruction are interdependent, and curriculum work needs to be approached with this important precept in mind.

We use two sets of research findings as the foundation for developing curriculum. First, a common curriculum with clear, intelligible standards that are aligned with appropriate assessments is critical to school improvement (Fullan & Stiegelbauer, 1991; Marzano, 2003; Rosenholtz, 1991). The lack of a clearly articulated curriculum hinders improvement efforts and, according to Mike Schmoker (2006), results in curriculum chaos. Second, in order for schools to improve, school personnel need to function as professional learning communities (DuFour & Eaker, 1998; Wagner, 2004; Wise, 2004). Teachers need ongoing opportunities to meet and plan common units and assessments. It is extremely difficult to develop professional learning communities if teachers are teaching different concepts at different points during the year. In order for districtwide improvement to happen, teachers must have the time to revise and develop curriculum that is focused on instruction.

Leaders can help teachers improve student achievement by implementing best instructional practices for teaching high content standards. In other words, school leaders must pay attention to both the curriculum ("what") and the instruction ("how"). The following fundamental concepts will ensure that the curriculum is aligned with instruction and will lay the cornerstone for curriculum development work:

- Learn, Then Do. Powerful professional development needs to be embedded in the curriculum development process.

- Develop Leadership Structure. Structures need to be in place to allow curriculum developers and leaders to supervise or work closely with building principals.

Learn, Then Do

Ann's experience illustrates what happens when the desire to produce a product trumps the process. When she ignored the curriculum development team's need to study effective instructional practices in science education, the overall quality of the final product was compromised. Writing curriculum isn't just about producing a guide. It includes defining what students need to know and do and giving teachers proven practices that will work with their specific content area. In order to avoid the pitfall of creating curriculum without a focus on instruction, we recommend two phases to manage the work. The first phase, planning and development, is used when an in-depth curriculum revision is needed; the second phase, review and evaluation, can help a team manage the curriculum after it is developed and ensure that it is implemented effectively.

Curriculum study and writing is a continuous improvement process, and subject-area curriculum teams will drive curriculum development for a district. Depending on the size of the district, representatives from every building, grade, and subject area should make up the teams. If the district is large, divide the teams by elementary and secondary schools. If the team is divided by elementary and secondary schools, it is critical for team members from transition grade levels (e.g., 5th and 8th grade teachers and administrators) to have opportunities to discuss grade-level matriculation. Representatives from other departments, such as library media, gifted and talented education, special education, ESL, Title I, and administrators from each elementary, middle, and high school should also be included on the team.

Simply having representative administrators from the central office on the curriculum team is not enough. The central office curriculum leader needs to ensure that building principals who are engaged in the curriculum and instruction process go beyond participating in meetings and help them make high levels of engagement with teaching and learning happen in their schools. The leadership structure section at the end of this chapter will address this concept in-depth.

The curriculum development team should review each curriculum document on an annual basis and have an in-depth revision and update for the curriculum on a six-to-eight year cycle as determined by the curriculum revision cycle. This development cycle is a critical piece to managing the work and the curriculum budget.

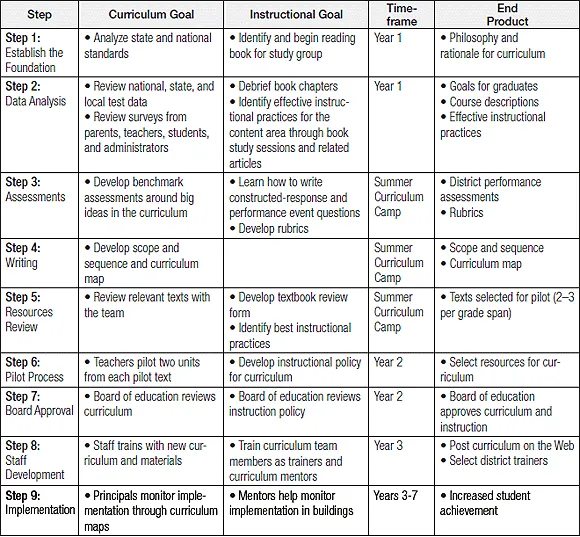

Figure 1.1 outlines each step during the planning and development phase. Each step includes specific promising practices to follow ("do's") and pitfalls to avoid ("don'ts").

Figure 1.1. The Planning and Development Process

Step 1: Establish the Foundation

This step sets the tone for the entire planning and development process.

Do

Do make sure that you spend significant time with the team to help them understand state and national standards. Most state assessments are based on national standards; therefore it is imperative that teachers have explicit knowledge about what students are expected to know. These standards are the driving force for curriculum development and will help teachers move away from negative thinking, such as "We've always done it this way" or "Our students won't be able to handle the information at that grade."

Don't

Don't forget to identify a book or a series of articles that will serve as the touchstone text for the curriculum revision process. Studying a book or a set of articles will serve as the cornerstone for the professional discussions that the team will have over the next few years. Thus, it is imperative to select texts that have proven instructional strategies instead of choosing lesson activities. The key in selecting materials for a group study is to understand the current district achievement data and the gaps that exist in teaching and learning practices throughout the district. For example, during a language arts curriculum revision, a preK–12 team chose Mosaic of Thought (Keene & Zimmerman, 1997) as their touchstone text and read selected chapters from Strategies That Work (Harvey & Goudvis, 2007) and Reading with Meaning (Miller, 2002). These selections helped them focus on their district's low reading comprehension scores on state and national tests and begin implementing reading strategies across the content areas. They also helped the team understand and identify what comprehension strategy instruction should look like in the classroom. Once the team had this understanding, developing a curriculum based on strategies that proficient readers could use was much easier.

Step 2: Data Analysis

This step focuses on developing a common understanding of the district's needs. The goal is for all team members to identify strengths and weaknesses in the district's curriculum by analyzing student achievement data.

Do

Do help teachers understand the implications of test scores beyond the scope of their own classroom. Make sure that teachers work in vertical teams to discuss achievement gaps at all levels. While more teachers have an opportunity to collaborate with their grade-level peers, it is extremely rare for teachers to discuss teaching and learning with their colleagues outside of their consecutive grade levels. When teachers have opportunities to talk with other teachers across all grade levels, the team broadens their understanding of major curriculum issues and begins to move from functioning as a group of individuals to working as a professional learning community.

According to DuFour (2004), a professional learning community is a team of teachers who meet on a regular basis to establish curriculum standards and collaborate on how to teach these standards. This is exactly the role that the district curriculum team should play. According to Marzano (2003), one of the most important factors that influence student achievement is developing a guaranteed and viable curriculum. This type of curriculum helps teachers identify a set of relevant standards and ensures that these standards are taught. In order to develop a guaranteed and viable curriculum, the curriculum development team must operate as a professional learning community.

There are two reasons for establishing a professional learning community at the district level. First, there is a general consensus among educational researchers that professional learning communities are one of the most promising strategies for significant and sustained school improvement. Members of the research community have developed a collective statement that supports the use of professional learning communities (Schmoker, 2006). The tools and processes outlined in this book are designed so that sustained improvements in achievement happen not only at the building level, but also at the district level. If long-term, sustained student achievement is the goal, district-level professional learning communities are not optional. Second, a district-level professional learning community can establish a model for developing curriculum for building principals and help them understand how to establish curriculum development teams in their schools.

Don't

Don't assume that all the members on the curriculum development team know enough about the topic to complete all the tasks at a high level. It is impossible to form a team where every member comes to the table with sufficient curricular and instructional knowledge. Some team members may need more experience or more opportunities to reflect on the topic from a different perspective. Savvy and successful curriculum leaders recognize that serving on a writing team is a high-level professional development task. These leaders know how to carry out the critical role of developing and training members of the writing team. Thus, professional development for the writing team must be embedded with information regarding what the data mean, strategies for including the most effective instructional practices in the content area, and data about the gaps in the current curriculum.

While it is necessary to produce a written curriculum to meet state and district requirements, the document becomes a by-product of learning how to deeply connect powerful curriculum with proven instructional methods.

Step 3: Assessments

The purpose of this step is to help the curriculum development team establish local benchmarks that will help teachers identify how well students understand the big ideas outlined in the curriculum standards. Starting curriculum development with assessments is not a new idea. Wiggins and McTighe's (1998) backward design model, which begins with identifying desired results, is a widely adopted standard for curriculum development. The objective of the backward design model is to help curriculum developers create units of study around major concepts in the curriculum. Units are designed to help students develop deep understandings of the concepts that are taught. Wiggins and McTighe recognize that teaching that is consistently geared toward deep and sophisticated understanding at all times is both impossible...