![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Setting Objectives and Providing Feedback

"The key to making your students' learning experiences worthwhile is to focus your planning on major instructional goals, phrased in terms of desired student outcomes—the knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and dispositions that you want to develop in your students. Goals, not content coverage or learning processes, provide the rationale for curriculum and instruction."

—Jere Brophy, Motivating Students to Learn

***

Imagine that you have to go to a city you haven't visited before. You know that cities have a variety of services and attractions, but you don't know exactly what you are supposed to do in this particular city. Should you provide a service for someone, gather information about a particular person or place, or do something else? Without a specific objective, you could spend your time on something that isn't important or that makes it difficult to know whether your time in the city was worth the trip.

Being in a classroom without knowing the direction for learning is similar to taking a purposeless trip to an unfamiliar city. Teachers can set objectives to ensure that students' journeys with learning are purposeful. When teachers identify and communicate clear learning objectives, they send the message that there is a focus for the learning activities to come. This reassures students that there is a reason for learning and provides teachers with a focal point for planning instruction. Providing feedback specific to learning objectives helps students improve their performance and solidify their understanding.

Setting objectives and providing feedback work in tandem. Teachers need to identify success criteria for learning objectives so students know when they have achieved those objectives (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Similarly, feedback should be provided for tasks that are related to the learning objectives; this way, students understand the purpose of the work they are asked to do, build a coherent understanding of a content domain, and develop high levels of skill in a specific domain. In this chapter, we present classroom practices for setting objectives and providing feedback that reassure students that their teacher is focused on helping them succeed.

Why This Category Is Important

Setting objectives is the process of establishing a direction to guide learning (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). When teachers communicate objectives for student learning, students can see more easily the connections between what they are doing in class and what they are supposed to learn. They can gauge their starting point in relation to the learning objectives and determine what they need to pay attention to and where they might need help from the teacher or others. This clarity helps decrease anxiety about their ability to succeed. In addition, students build intrinsic motivation when they set personal learning objectives.

Providing feedback is an ongoing process in which teachers communicate information to students that helps them better understand what they are to learn, what high-quality performance looks like, and what changes are necessary to improve their learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Shute, 2008). Feedback provides information that helps learners confirm, refine, or restructure various kinds of knowledge, strategies, and beliefs that are related to the learning objectives (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). When feedback provides explicit guidance that helps students adjust their learning (e.g., "Can you think of another way to approach this task?"), there is a greater impact on achievement, students are more likely to take risks with their learning, and they are more likely to keep trying until they succeed (Brookhart, 2008; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Shute, 2008).

The results from McREL's 2010 study indicate that the strategies of setting objectives and providing feedback have positive impacts on student achievement. The 2010 study provides separate effect sizes for setting objectives (0.31) and providing feedback (0.76). These translate to percentile gains of 12 points and 28 points, respectively. The first edition of this book reported a combined effect size of 0.61, or a percentile gain of 23 points, for this category. Differences in effect sizes may reflect the different methodologies used in the two studies, as well as the smaller study sample size (four studies related to setting objectives; five studies related to providing feedback) and the specific definitions used in the 2010 study to describe the two strategies.

Studies related to setting objectives emphasize the importance of supporting students as they self-select learning targets, self-monitor their progress, and self-assess their development (Glaser & Brunstein, 2007; Mooney, Ryan, Uhing, Reid, & Epstein, 2005). For example, in the Glaser and Brunstein study (2007), 4th grade students who received instruction in writing strategies and self-regulation strategies (e.g., goal setting, self-assessment, and strategy monitoring) were better able to use their knowledge when planning and revising a story, and they wrote stories that were more complete and of higher quality than the stories of control students and students who received only strategy instruction. In addition, they retained the level of performance they reached at the post-test over time, and when asked to recall parts of an orally presented story, the strategy plus self-regulation students scored higher on the written recall measure than did students in the other two groups.

The studies related to feedback underscore the importance of providing feedback that is instructive, timely, referenced to the actual task, and focused on what is correct and what to do next (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Shute, 2008). They also address the use of attributional and metacognitive feedback. For example, a study by Kramarski and Zeichner (2001) investigated the use of metacognitive feedback versus results feedback in a 6th grade mathematics class as a way to help students know what to do to improve their performance. Metacognitive feedback was provided by asking questions that served as cues about the content and structure of the problem and ways to solve it. Results feedback provided cues related to the final outcome of the problem. Students who received metacognitive feedback significantly outperformed students who received results feedback, in terms of mathematical achievement and the ability to provide mathematical explanations. They were more likely to provide explanations of their mathematical reasoning, and those explanations were robust—they included both algebraic rules and verbal arguments.

Classroom Practice for Setting Objectives

At a minimum, setting objectives involves clearly communicating what students are to learn. The classroom practices presented in this chapter emphasize that there are additional actions teachers should take to maximize this strategy's potential for improving student achievement.

There are four recommendations for setting objectives in the classroom:

- Set learning objectives that are specific but not restrictive.

- Communicate the learning objectives to students and parents.

- Connect the learning objectives to previous and future learning.

- Engage students in setting personal learning objectives.

Set learning objectives that are specific but not restrictive

The process of setting learning objectives begins with knowing the specific standards, benchmarks, and supporting knowledge that students in your school or district are required to learn. State and local standards or curriculum documents are generally the source for this information. Often, standards are written at a fairly general level. If they are not too broad, they might serve as learning objectives at the course or unit level. Often, teachers must "unpack" the statements of knowledge in their standards document to drill down to more specific statements of knowledge and skills that can serve as the focus for instructional design and delivery. For example, as a 3rd grade teacher prepares to design and deliver writing instruction, he or she might encounter the following 3rd grade standard and expectation:

Standard: Use the general skills and strategies of the writing process.

Benchmark: Write informative/explanatory text to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

In this example, the standard is written at a very general level. The benchmark statement is more specific and could serve as the learning objective for a unit or portion of a unit. Notice that the benchmark provides detail about what the student must be able to do (write informative/explanatory text) and for what purpose (to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly). To identify learning objectives for individual lessons, the teacher might begin by asking the question "What does it mean for students to write informative/ explanatory text to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly?" By answering this question, the teacher can determine what students must know, understand, and be able to do.

In this example, the teacher may use the unpacking process to determine that, in order to demonstrate proficiency, students need to be responsible for the entire process of writing a paragraph that groups sentences around a specific topic. This includes

- Generating the topic, instead of receiving the topic from the teacher.

- Understanding the procedure for writing a complete paragraph.

- Demonstrating the ability to write a complete paragraph that includes an introductory sentence, supporting sentences, and a concluding sentence, without the aid of sentence starters or similar assistance.

- Demonstrating the ability to establish and maintain coherence throughout a paragraph by aligning sentences with one another and to the topic.

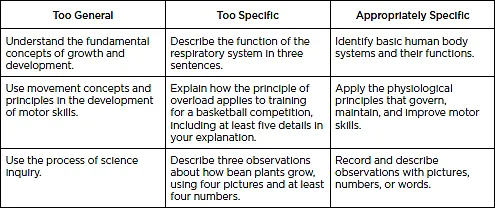

The teacher uses the knowledge and skills identified through the unpacking process to develop lesson objectives. These objectives explicitly focus instruction on guiding students toward proficiency with the content knowledge and skills expressed in the standards document. Learning objectives should not be so broad that they are meaningless or so narrow that they limit learning or provide few opportunities for differentiation. Figure 1.1 presents examples of learning objectives that are too general, too specific, and appropriately specific.

To provide the guidance that students need, learning objectives should be stated in terms of what students are supposed to learn, not what activity or assignment they are expected to complete. For example, "Understand how white settlers interacted with American Indians" is a learning objective, and "Read pages 14–17 and answer the questions about ways that white settlers interacted with American Indians" is a learning activity. The learning objective is what students should know, understand, or be able to do as a result of completing the learning activity or assignment. Stating learning objectives as statements of knowledge underscores the point that attaining objectives is about acquiring knowledge rather than competing against others (Brophy, 2004).

Figure 1.1. Specificity of Learning Objectives

Communicate the learning objectives to students and parents

It is important to communicate learning objectives to students explicitly by stating them verbally, displaying them in writing, and calling attention to them throughout a unit or lesson. Clearly stating the learning objectives in student-friendly language helps students focus on what you want them to learn.

Communicating learning objectives to parents helps them understand and become engaged in what their children are learning. When thus informed, parents can then ask their children specific questions, such as "What did you learn today about safety rules in the home and school?" or "What's the most interesting thing about the different states of matter?" Providing multiple options—blogs, text messages, e-mails, letters—for parents to access information about learning objectives sends the message that you value their involvement.

Example

Administrators at a school in Saipan are experiencing some difficulty as they attempt to identify learning objectives during their regular classroom walkthroughs. They suppose that if they are having a difficult time, then students might be experiencing a similar frustration. After teachers understand the administrators' concerns, they decide to denote an area on the classroom boards where the objective can always be found. Each teacher sections off a square of his or her board and then divides the square into two columns. In the left column, teachers write the learning objectives. In the right column, they write the learning activity that the class will focus on during each day or period. Now, anyone who enters the classroom—students, visitors, or administrators—can quickly find the objective and know exactly what is happening each day.

Many teachers now use social media to communicate learning objectives to audiences outside the classroom. For example, a teacher might post weekly objectives on his or her class blog or wiki. Tools such as blogs, websites, and social media pages allow parents to have immediate and accurate access to what is happening in the classroom.

Connect the learning objectives to previous and future learning

Teachers should explain how learning objectives connect with previous lessons or units or with the larger picture of a particular unit or course (Brophy, 2004; Urdan, 2004). Although most teachers do this naturally, this recommendation is meant to ensure that educators explicitly call students' attention to how the current learning objective is connected to something they have already learned and how they will apply what they are learning now to future studies.

Example

Mr. Jackson, a 4th grade mathematics teacher, wants to be sure his students understand the connections between what they are doing in a given day's lesson and previous lessons on the same topic. He tells his students, "We've been learning how to add and subtract fractions with like denominators. Today, we're going to apply that knowledge and what we learned about writing equivalent fractions to add fractions with unlike denominators. Eventually, you will be able to apply this knowledge to a cooking activity in which you will combine ingredients to make a Fall Festival cake."

This practice helps Mr. Jackson's students build a more complete mental image of the topic being studied, and it encourages them to commit to the learning objectives.

Engage students in setting personal learning objectives

Providing opportunities for students to personalize the learning objectives identified by the teacher can increase their motivation for learning (Brophy, 2004; Morgan, 1985; Page-Voth & Graham, 1999). Students feel a greater sense of control over what they learn when they can identify how the learning is relevant to them. In addition, this practice helps students develop self-regulation (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Students who are skilled at self-regulation are able to consciously set goals for their learning and monitor their understanding and progress as they engage in a task. They also can plan appropriately, identify and use necessary resources, respond appropriately to feedback, and evaluate the effectiveness of their actions. Acquiring these skills helps students become independent lifelong learners.

Many students do not have experience with writing their own learning objectives, so it is important for teachers to model the process and provide students with feedback when they are first learning how to set their own learning objectives (White, Hohn, & Tollefson, 1997). Teachers can guide students in the process by

- Providing them with sentence stems such as "I know that … but I want to know more about … " and "I want to know if … " Younger students can write "I can" or "I will" statements.

- Asking them to complete a K-W-L chart as a way to record what they know (K) about the topic, what they want (W) to know as a result of the unit or lesson, and what they learned (L) as a result of the unit or lesson (Ogle, 1986). Students can complete the L section throughout the unit or lesson. Adding a column labeled "What I Think I Know" reduces stress about being correct and expands students' thinking.

- Checking their learning objectives to ensure they are meaningful and attainable within the given time period and with available resources.

If students do not have enough prior knowledge to set personal learning objectives at the beginning of a unit, delay this task until they have e...