![]()

Chapter 1

The Importance of Background Knowledge

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2003), every day from September to June some 53.5 million students in the United States walk into classes that teach English, mathematics, science, history, and geography and face the sometimes daunting task of learning new content. Indeed, one of the nation’s long-term goals as stated in the The National Education Goals Report: Building a Nation of Learners (National Education Goals Panel, 1991) is for U.S. students to master “challenging subject matter” in core subject areas (p. 4). Since that goal was articulated, national and state-level standards documents have identified the challenging subject matter alluded to by the goals panel. For example, in English, high school students are expected to know and be able to use standard conventions for citing various types of primary and secondary sources. In mathematics, they are expected to understand and use sigma notation and factorial representations. In science, they are expected to know how insulators, semiconductors, and superconductors respond to electric forces. In history, they are expected to understand how civilization developed in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. In geography, they are expected to understand how the spread of radiation from the Chernobyl nuclear accident has affected the present-day world.

Although it is true that the extent to which students will learn this new content is dependent on factors such as the skill of the teacher, the interest of the student, and the complexity of the content, the research literature supports one compelling fact: what students already know about the content is one of the strongest indicators of how well they will learn new information relative to the content. Commonly, researchers and theorists refer to what a person already knows about a topic as “background knowledge.” Numerous studies have confirmed the relationship between background knowledge and achievement (Nagy, Anderson, & Herman, 1987; Bloom, 1976; Dochy, Segers, & Buehl, 1999; Tobias, 1994; Alexander, Kulikowich, & Schulze, 1994; Schiefele & Krapp, 1996; Tamir, 1996; Boulanger, 1981). In these studies the reported average correlation between a person’s background knowledge of a given topic and the extent to which that person learns new information on that topic is .66 (see Technical Note 1 for a discussion of how the correlation was computed).

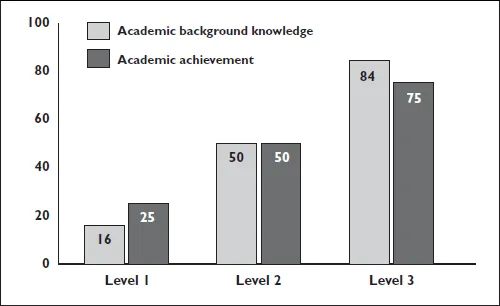

To interpret this average correlation, let’s consider one student, Jana, who is at the 50th percentile in terms of both her background knowledge and her academic achievement. Envision Jana’s achievement at the 50th percentile as shown in the middle of Figure 1.1. (For a more detailed explanation of this example, see Technical Note 2.) If we increase her background knowledge by one standard deviation (that is, move her from the 50th to the 84th percentile), her academic achievement would be expected to increase from the 50th to the 75th percentile (see the bars on the right side of Figure 1.1). In contrast, if we decrease Jana’s academic background knowledge by one standard deviation (that is, move her from the 50th to the 16th percentile), her academic achievement would be expected to drop to the 25th percentile (see the bars on the left side of Figure 1.1). These three scenarios demonstrate the dramatic impact of academic background knowledge on success in school. Students who have a great deal of background knowledge in a given subject area are likely to learn new information readily and quite well. The converse is also true.

Figure 1.1. Academic Achievement at Three Levels of Academic Background Knowledge

Academic background knowledge affects more than just “school learning.” Studies have also shown its relation to occupation and status in life. Sticht, Hofstetter, and Hofstetter (1997) sought to document a relationship between background knowledge and power, with power defined as “the achievement of a higher status occupation and/or the ability to earn an average or higher level income” (p. 2). To test their hypothesis that “knowledge is power” (p. 3), they interviewed 538 randomly selected adults and gave them a test of basic academic information and terminology. They found a significant relationship between knowledge of this academic information and type of occupation and overall income.

This discussion paints a compelling picture of the impact of academic background knowledge on students’ academic achievement in school and on their lives after school. It is important to note the qualifier academic. Two students might have an equal amount of background knowledge. However, one student’s knowledge might relate to traditional school subjects such as mathematics, science, history, and the like. The other student’s knowledge might be about nonacademic topics such as the best subway route to take to get downtown during rush hour, the place to stand in the subway car that provides the most ventilation on a hot summer day, and so on. The importance of one type of background knowledge over another is strictly a function of context (Becker, 1977; Greenfield, 1998). The background knowledge of the second student is critical to successfully using public transportation in a specific metropolitan area, but probably not very important for success in school. The first student’s background knowledge is critical to success in school but not to successful public transit.

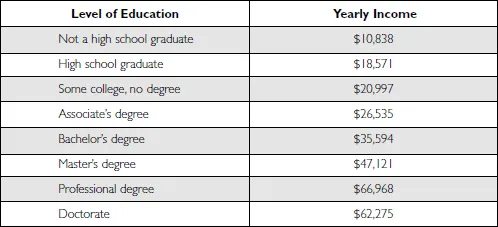

This book is about enhancing students’ academic background knowledge. This is not to say that other types of background knowledge are unimportant. Indeed, Sternberg and Wagner’s (1986) compilation of the research on practical intelligence makes a good case that success in many aspects of life is related to nonacademic types of background knowledge. However, it is also true that in the United States all children are expected to attend school, and success in school has a strong bearing on their earning potential. Figure 1.2 illustrates the dramatic rise in yearly income as the level of education increases. One particularly disturbing aspect of Figure 1.2 is the income level of those who have not graduated from high school—namely, $10,838. This is not much above the official poverty line in the United States, which is $9,359 per year for a single adult (U.S. Census Bureau, September 25, 2003). Students who do not graduate from high school likely condemn themselves to a life of poverty.

Figure 1.2. Relationship Between Education and Yearly Income

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March 2003

Enhancing students’ academic background knowledge, then, is a worthy goal of public education from a number of perspectives. In fact, given the relationship between academic background knowledge and academic achievement, one can make the case that it should be at the top of any list of interventions intended to enhance student achievement. If not addressed by schools, academic background can create great advantages for some students and great disadvantages for others. The scope of the disparity becomes evident when we consider how background knowledge is acquired.

How We Acquire Background Knowledge

We acquire background knowledge through the interaction of two factors: (1) our ability to process and store information, and (2) the number and frequency of our academically oriented experiences. The ability to process and store information is a component of what cognitive psychologists refer to as fluid intelligence. As described by Cattell (1987), fluid intelligence is innate. One of its defining features is the ability to process information and store it in permanent memory. High fluid intelligence is associated with enhanced ability to process and store information. Low fluid intelligence is associated with diminished ability to process and store information.

Our ability to process and store information dictates whether our experiences parlay into background knowledge. To illustrate, consider two students who visit a museum and see exactly the same exhibits. One student has an enhanced capacity to process and store information, or high fluid intelligence; the other has a diminished capacity to process and store information, or low fluid intelligence. The student with high fluid intelligence will retain most of the museum experience as new knowledge in permanent memory. The student with low fluid intelligence will not. In effect, the student with the enhanced information-processing capacity has translated the museum experience into academic background knowledge; the other has not. As Sternberg (1985) explains: “What seems to be critical is not sheer amount of experience but rather what one has been able to learn from and do with experience” (p. 307).

The second factor that influences the development of academic background knowledge is our academically oriented experiential base—the number of experiences that will directly add to our knowledge of content we encounter in school. The more academically oriented experiences we have, the more opportunities we have to store those experiences as academic background knowledge. Again, consider our two students at the museum. Assume that one student has an experience like visiting a museum once a week and the other student has experiences like this once a month. The second student might have an equal number of other types of experiences, but they are nonacademic and provide little opportunity to enhance academic background knowledge. In effect, the first student has four times the opportunities to generate academic background knowledge as the second, at least from “museum-type” experiences.

It is the interaction of students’ information-processing abilities and their access to academically oriented experiences, then, that produces their academic background knowledge. Differences in these factors create differences in their academic background knowledge and, consequently, differences in their academic achievement.

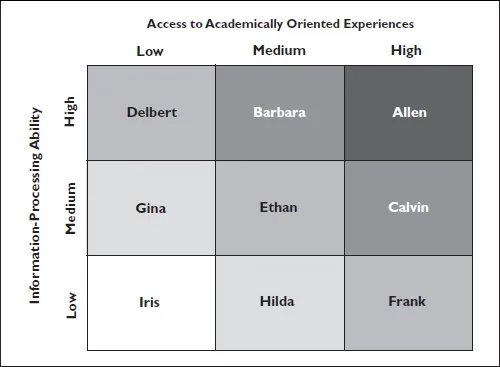

An examination of the interaction of these factors paints a sobering picture of the academic advantages possessed by some students and not others. Figure 1.3 depicts nine students with differing levels of access to academically oriented experiences and differing levels of ability to process and store information. The darker the box, the more academic background knowledge a student has. Allen has the most background knowledge. He has a great deal of access to experiences that build academic background knowledge and exceptional ability to process and store those experiences. We might say that Allen is doubly blessed because of his ability to process information and his access to many experiences that will be translated into academic background knowledge. Barbara and Calvin are next in order of the amount of academic background knowledge but for slightly different reasons. Barbara has midlevel access to experiences but a highly developed ability to process and store information. She makes maximum use of her academically oriented experiences. Calvin doesn’t have Barbara’s ability to process and store information, but he has many experiences to draw from. As Figure 1.3 demonstrates, enhanced information-processing ability can offset to some degree lack of access to academically oriented experiences, and vice versa. Figure 1.3 also demonstrates the plight of certain students who—I assert—constitute the academically disadvantaged students in the United States. Consider the three students depicted in the first column of Figure 1.3—Delbert, Gina, and Iris.

Figure 1.3. Interaction of Factors Affecting Academic Background Knowledge

Delbert has a moderate amount of background knowledge, but only because he has exceptional ability to process and store information. Even though he has little access to experiences, he stores most of what he experiences. Gina has an average ability to process information, but her limited access to background knowledge plays havoc with her chances of developing a large store of academic background knowledge. Iris is in the worst situation of all. She has diminished information-processing ability and limited access to academically oriented experiences. Limited access to academic background experiences, then, represents “the great inhibitor” to the development of academic background knowledge. We might ask, which students characteristically have limited access to academic background experience? Stated differently, who are Delbert, Gina, and Iris?

The Consequences of Poverty

The plight of Delbert, Gina, and Iris becomes particularly disturbing when we consider the direct relationship between access to academic background experiences and family income. Unfortunately, a great many children attending U.S. schools grow up in poverty. Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, and Maritato (1997) note that “in a given year from 1987 to 1996, about one in five of all American children—from twelve to fourteen million—lived in families in which total income failed to exceed even the Spartan thresholds used to define poverty” (p. 1). Relatively speaking, this is not an insignificant number. As Brooks-Gunn and colleagues explain: “Indeed, the United States has a higher rate of poverty than most other Western industrialized nations … and … child poverty has increased since the 1970s….” (p. 12).

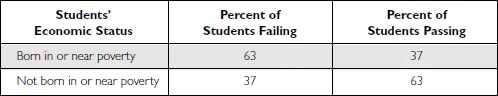

Even without considering the impact of poverty on access to academically oriented experiences, the relationship between poverty and academic achievement is almost self-evident. To illustrate, Smith, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov (1997) analyzed data from two studies: the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) and the Infant Health and Development Project (IHDP). The NLSY involved children of women who were first studied when they were teenagers. The children were tracked beginning in 1986 and every year after that. The IHDP followed children born in eight medical centers across the United States each year for the first five years of their lives. Aggregating the findings from both studies as reported by Smith and colleagues dramatizes the impact of family income on academic achievement. Consider two groups of children ages 3–7. The children in one group were born in or near poverty, and those in the other group were not. Assume that children in both categories took an academic test of mathematics, general verbal intelligence, and reading, and that test had an expected passing rate of 50 percent. Figure 1.4 indicates that based on the findings from Smith and colleagues, only 37 percent of those students born in or near poverty would pass the test, whereas 63 percent of those not born in or near poverty would pass. What is most interesting about the findings reported in Figure 1.4 is that they characterize the relationship between poverty and academic success after controlling for ethnicity, family structure, and mothers’ education. In other words, the relationship depicted in Figure 1.4 is what would be expected if all children in the studies from which the data were taken were equal in terms of their ethnicity, their mother’s education level, and whether they came from a single-parent home, a two-parent home, or an intact family. These qualifiers put the impact of family income in sharp perspective. Even if children are equal in these admittedly important factors, the influence of family income creates huge discrepancies in academic success.

Figure 1.4. Relationship Between Poverty and Success on an Academic Test

Source: Based on data in Smith, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1997. For an explanation of how this figure was constructed, see Technical Note 3.

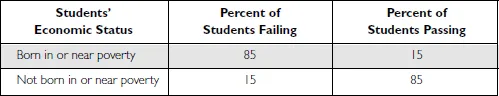

Some researchers believe that family income has an even greater impact on achievement than that depicted in Figure 1.4. For example, McLanahan (1997) notes that “income is clearly the most important factor. It explains about 50 percent of the difference in the educational achievement of children raised in oneand two-parent families” (p. 37). Using McLanahan’s figures to compute the impact of poverty on students’ success on an academic test produces the results reported in Figure 1.5. As the figure shows, only 15 percent of students who grow up in or near poverty are expected to pass a test that we would normally expect half the students to pass and half the students to fail. Regardless of which figure (1.4 or 1.5) depicts the true relationship, the message is clear: Poverty has a profound impact on academic achievement.

Figure 1.5. Relationship Between Poverty and Success on an Academic Test Using McLanahan’s Estimates

Source: Based on data in McLanahan, 1997. For an explanation of how these percentages were computed, see Technical Note 3.

The Influence of Poverty on Factors Other Than Academic Achievement

Poverty’s negative impact goes well beyond academic achievement. For example, poverty has been associated with an increase in conflicts at home. Conger, Conger, and Elder (1997) explain:

… we propose that the psychological stresses and strains associated with economic pressure increase the risk for conflicts between parents about their finances. Spouses who are angered and demoralized by their disadvantaged economic situation and who have to negotiate with one another about the use of scarce resources are living in a situation ripe for conflicts…. (p. 302)

It makes intuitive sense that a lack of financial resources puts extraordinary stress on spousal relationships, which translates into more frequent family conflict. Children who are unable to comprehend the dynamics of such conflicts might easily believe that they are somehow responsible for the strife. Also, because wealth is a symbol of success in U.S. society, it is not surprising that poverty is a symbol of failure, leading to a decrease in self-esteem. As Axinn, Duncan, and Thornton (1997) explain:

Parents’ economic resources can influence self-esteem in several ways. Parents’ income brings both parents and children social status and respect that can translate into individual self-esteem. Income can also enhance children’s self-esteem by providing them with goods and services that satisfy individual aspirations.

Low income and other economic hardships may reduce children’s self-esteem by reducing the emotional or supportive qualities of the parents’ home. The pressure that limited economic resources can place on marital relationships can, in turn, translate into negative parent-child relations and lower levels of self-esteem. (p. 521)

Some of the more dramatic...