![]()

Chapter 1

Understanding Joyful Learning in Social Studies

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Joyful teaching and learning in social studies encompasses "acquiring knowledge or skills in ways that cause pleasure and happiness" (Opitz & Ford, 2014, p. 10). As discussed in the Introduction, the joyful learning process requires and builds on noncognitive skills as well as academic knowledge. Skills such as resilience, persistence, determination, and a willingness to problem solve lay the foundation for joy in learning. Structuring teaching practice around affective outcomes capitalizes on the pleasures of learning and leads to knowledge, thinking, and inquiry.

The National Council for the Social Studies (2010) has described the goal of social studies as "the promotion of civic competence—the knowledge, intellectual processes, and democratic dispositions required of students to be active and engaged participants in public life" [emphasis added] (p. 210). Therefore, success in the learning process for social studies learners results in effective participation in public life. Teachers can support this goal if they are able to help students develop knowledge, thinking processes, and an inquiring disposition.

Learning and development is encouraged by different types of rewards: autonomous, social, and tension/release (Olson, 2009). Specific examples of these rewards are the innate pleasure of a learning experience, feedback and encouragement, and the pleasure that comes from overcoming a potential stressful situation to achieve. Focusing on joyful learning ensures that these types of reward outcomes for students are incorporated in activities in the social studies classroom.

Joyful teaching and learning in social studies depend on sustainable long-term inquiry—across a whole school year or longer—that helps students see the big picture. Planning a single day's lesson or a two-week unit needs to be part of a much larger vision. This vision includes not only the content objectives of the curriculum but also the participation of and interaction with the learner. When striving to create a joyful learning environment, it is important to understand how essential students' motivation and engagement will be to its success.

Motivation and Engagement

Although many people use the words engagement and motivation as if they were synonymous, differences in connotation are important for our practice as teachers. Motivation is the drive or the cause of actions. Engagement describes how people think and act while they are in the thick of the action. Motivation creates a narrative arc for what people do, framing it with a beginning and a projected ending. But as with most good stories, the meat of the narrative happens in the middle, under the arc. Focusing on student motivation generates outcomes in engagement. When students are engaged learners, joy emanates from success in the learning process (Rantala & Maatta, 2012; Schlechty, 2011; Tough, 2012).

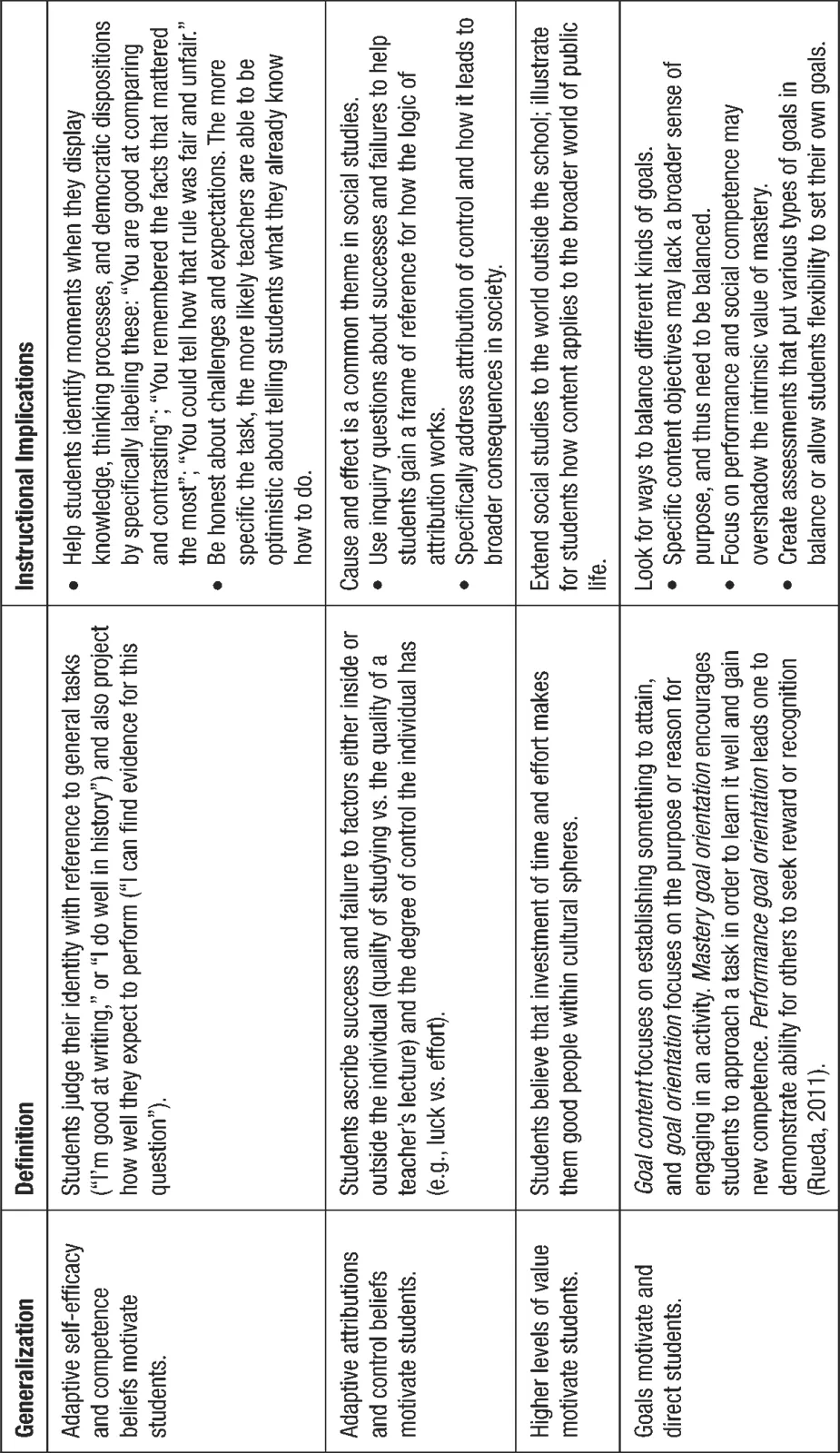

In their foundational book for this series, Opitz and Ford (2014) outlined factors that influence motivation, including self-efficacy and competence beliefs, attributions and control beliefs, perceptions of value, and goal orientation. Figure 1.1 illustrates how we can use understanding of these motivational factors to enhance our teaching of social studies.

FIGURE 1.1. Generalizations About Motivation, and Implications for the Social Studies Classroom

Generalizations adapted from Pintrich, Marx, & Boyle (1993); table adapted from Opitz & Ford (2014, p. 12–13).

Any discussion of motivation and engagement must address the concept of entertainment and audience (i.e., student) participation. The key difference between entertainment and education is direction: whereas entertainment is directed toward an audience, education is the effort to draw the audience out—eliciting interaction. Entertainment expects little effort on the part of the audience; any engagement stems almost entirely from the qualities and design of the presentation. Engagement in education venues should rely less on the external "entertaining" qualities of presentation (although these are part of the social studies teacher's toolkit) and more on the student's internalized attributes of inquiry and the satisfaction experienced in pursuing evidence.

Students will encounter multiple presentations of information along the way, and they will certainly need to be able to evaluate how well these presentations are crafted. However, very little powerful growth in social studies happens under a transmission model of learning and teaching. Student research and inquiry, service learning, and performance outcomes are better suited to an active, student-oriented model of concept development in social studies. Rather than putting on a show, teachers should orchestrate progress for many students addressing different aspects of projects.

My suggestion of incorporating students into projects does not to discourage teachers from presenting material in a dramatic way. Doing something a little out of the ordinary such as wearing period costumes can make historical images concrete for learners, while also modeling our own love for and identification with social studies. Incorporating this kind of showmanship only a few times a year makes entertainment a kind of punctuation on the broader paragraphs and pages of students' ongoing inquiry.

Motivating and Engaging Students in Social Studies

Success in social studies depends on learners building new concepts, making connections to their lives, and overcoming misconceptions (Brophy & Alleman, 2007). At the same time, social studies makes powerful demands on vocabulary learning. Any kind of concept development takes time, and we should encourage our students to ask the type of social studies questions that further conceptual growth:

- Why do people do what they do?

- Who makes the decisions?

- Who is in charge and how did they get there? Who is following, and why?

- Who wants what, and what is the result of these desires?

- What changes as years pass?

Units of study in social studies should be broad enough to allow students to consider these questions over months of time; they are not linked to any specific unit, but rather provide a foundation for learning. A broad approach to social studies may mean teaching fewer topics per year, but it will result in greater depth and conceptual development.

Students need time to process information. Too often we prepare information and teach it as if the students had been there with us while we prepared. When we present new information, we have to remember that students need time to connect and think about it. There are many variations on the theme of asking and answering questions; using strategies such as pair-share give students an opportunity to take new information and do something with it right now.

Student Choice and Autonomy

The best way to incorporate choice and autonomy in social studies assignments is to offer students a menu of options; I have found that it is easier for students to select than to identify their own ideas for inquiry. However, we should give our strongest students the opportunity to think and choose freely, or we will miss an opportunity to help them grow. Remember, all the growth we encourage in social studies classes is supposed to lead to active, engaged participation in public life—now, not sometime later in life. Providing students choices in how to demonstrate their understanding engages them and encourages this active participation.

We also should offer students some measure of choice in working independently or collaboratively. In middle school classes, there are always one or two students who just cannot stop talking and are often moving around the classroom and interrupting other students. Looking at this as a student need rather than a distraction, however, can change our approach to teaching social studies. Offering these "social butterflies" the opportunity to work with others helps them succeed as learners. Similarly, other students prefer to work alone, and we need to include those opportunities as well. This is consistent with social developmental theory (Vygotsky, 1978); whereas some need public dialogue to structure their learning and thinking, others prefer to engage in private silent dialogue. Teachers who are in tune with students' social preferences and needs as learners can design flexible groupings (Opitz, 1998) that follow students' ideas for what they want and need in social studies.

Self-Assessment

In all areas of sociology and psychology, researchers worry about the biasing effects of self-reported data—that people are likely to say what they think they should say instead of what they really think or feel. However, when compared with objective measures of happiness such as having needs met, having opportunities for fulfillment, or having degrees of freedom in life, self-reports match tidily (Diener, 2000; Stone, Schwartz, Broderick, & Deaton, 2010).

What this means for us as teachers is that we can gather useful information about joyful teaching and learning by talking with students. We also need to share information about their subjective well-being. As we discover and experience joy and challenges in our own social studies inquiries, thinking aloud about these experiences models self-assessment and helps students feel enabled to communicate in school about their own experience.

The same principle of self-reporting can be used in structured assessments to gather information on students' interests, attitudes, and identities. Opitz, Ford, and Erekson (2011) presented inventories, surveys, and interview protocols as structures for self-reporting data. One reason for collecting structured data of this type is that when they are compiled for an entire class, teachers can analyze them for trends and patterns that influence teaching decisions (e.g., to structure inquiry learning activities). Anecdotal notes taken during learner conferences will provide valuable additional data to triangulate what is learned using more s...