![]()

Chapter 1

Neurodiversity: The New Diversity

Defects, disorders, diseases can play a paradoxical role, by bringing out latent powers, developments, evolutions, forms of life, that might never be seen, or even be imaginable, in their absence.

—Oliver Sacks, neurologist

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

It was the start of a new school year. Mr. Farmington, a first-year 5th grade teacher, was perusing his roster of incoming students when it hit him like a ton of bricks: In his class this year, he was going to have two students with learning disabilities, one student with ADHD, one with autism, one with Down syndrome, and one with an emotional disorder. In a class of 30 students, this ratio seemed like too much to bear. Inclusion is all well and good, thought Mr. Farmington, but he already had too much to do. Disgruntled, he took his roster and his misgivings to his principal, Ms. Silvers.

"I'm not trained as a special education teacher," he told her. "Who's going to help me with all the problems I'm going to face with these kids?"

Ms. Silvers listened carefully to Mr. Farmington's concerns. She understood where he was coming from. She'd heard complaints like his from teachers before and had often responded by reassigning at least some of the special education kids to other classrooms. But in this case, she decided to handle the situation a little bit differently.

"Bill," she said, "I know that you're thinking about these kids as problems and believe that they're just going to make your year harder. First of all, let me assure you that you're going to get a lot of support from the special education staff. But there's something else I want you to know. What if I were to tell you that these kids have talents and abilities that are going to enhance your classroom, and that even might make your year easier and more enjoyable? One of the boys that we diagnosed as having a learning disability is totally into machines and can fix just about anything mechanical. The child with autism is absolutely obsessed with military battles, which should be an asset in your history lessons. The girl with Down syndrome was reported by her 4th grade teacher to be one of the friendliest kids she'd ever worked with in her 30 years of teaching. And the boy with an emotional disorder happens to be an artist who has exhibited his work at a local art gallery."

"Wow," said Mr. Farmington. "I had no idea. I guess I was just reacting to their labels. Thanks for the heads-up."

Mr. Farmington left the meeting with a new, more positive attitude about his kids with special needs and a greater willingness to give them a chance to succeed in his classroom.

The above scenario may strike some as overly optimistic, but it raises an important question: Is it better to think about students with special needs as liabilities or as assets? If it's better to perceive them as assets, then why aren't we doing a better job of identifying their strengths? Google the phrase "strengths of students in special education," and you're likely to find a wide selection of websites focused on the pros and cons of inclusion and labeling, but practically nothing about the specific strengths of kids in special education.

The truth is that since the beginning of special education in the early 1950s, the conversation about children with special needs has been almost exclusively a disability discourse. In one way this makes perfect sense. After all, we're talking about kids who are labeled as special education students precisely because they've had difficulties of one kind or another in the classroom. But if we truly want to help these kids succeed in school and in life, it seems to me that we need to make a comprehensive, all-out inventory of their strengths, interests, and capabilities. To do this, we need a new paradigm that isn't solely based upon deficit, disorder, and dysfunction. Fortunately, a new way of thinking about students with special needs has emerged on the horizon to help us: neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity: A Concept Whose Time Has Come

The idea of neurodiversity is really a paradigm shift in how we think about kids in special education. Instead of regarding these students as suffering from deficit, disease, or dysfunction, neurodiversity suggests that we speak about their strengths. Neurodiversity urges us to discuss brain diversity using the same kind of discourse that we employ when we talk about biodiversity and cultural diversity. We don't pathologize a calla lily by saying that it has a "petal deficit disorder." We simply appreciate its unique beauty. We don't diagnose individuals who have skin color that is different from our own as suffering from "pigmentation dysfunction." That would be racist. Similarly, we ought not to pathologize children who have different kinds of brains and different ways of thinking and learning.

Although the origins of the neurodiversity movement go back to autism activist Jim Sinclair's 1993 essay "Don't Mourn for Us," the term neurodiversity was actually coined in the late 1990s by two individuals: journalist Harvey Blume and autism advocate Judy Singer. Blume wrote in 1998, "Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general. Who can say what form of wiring will prove best at any given moment? Cybernetics and computer culture, for example, may favor a somewhat autistic cast of mind." In 1999, Singer observed, "For me, the key significance of the 'Autistic Spectrum' lies in its call for and anticipation of a politics of Neurological Diversity, or what I want to call 'Neurodiversity.' The 'Neurologically Different' represent a new addition to the familiar political categories of class/gender/race and will augment the insights of the social model of disability" (p. 64).

According to a widely disseminated definition on the Internet, neurodiversity is "an idea which asserts that atypical (neurodivergent) neurological development is a normal human difference that is to be recognized and respected as any other human variation." The online Double-Tongued Dictionary characterizes neurodiversity as "the whole of human mental or psychological neurological structures or behaviors, seen as not necessarily problematic, but as alternate, acceptable forms of human biology" (2004). The term neurodiversity has gathered momentum in the autistic community and is spreading beyond it to include groups identified with other disability categories including learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, ADD/ADHD, and mood disorders (see, for example, Antonetta, 2007; Baker, 2010; Hendrickx, 2010; and Pollock, 2009).

This new term has great appeal because it reflects both the difficulties that neurodiverse people face (including the lack of toleration by so-called "normal" or "neurotypical" individuals) as well as the positive dimensions of their lives. Neurodiversity helps make sense of emerging research in neuroscience and cognitive psychology that reveals much about the positive side of individuals with disabilities. It sheds light on the work of Cambridge University researcher Simon Baron-Cohen, who has investigated how the strengths of individuals with autism relate to systems thinking in fields such as computer programming and mathematics (Baron-Cohen, 2003). It manifests itself in the work of University of Wisconsin and Boston College researchers Katya von Karolyi and Ellen Winner, who have investigated the three-dimensional gifts of people with dyslexia (Karolyi, Winner, Gray, & Sherman, 2003). It shows up in the works of best-selling author and neurologist Oliver Sacks, whose many books of essays chronicle the lives of neurodiverse individuals (a term he doesn't use, but of which I think he would approve) as they experience both the ups and downs of their atypical neurological makeup (Sacks, 1996, 1998, 2008).

We should keep in mind that the term neurodiversity is not an attempt to whitewash the suffering undergone by neurodiverse people or to romanticize what many still consider to be terrible afflictions (see Kramer, 2005, for a critique of those who romanticize depression). Rather, neurodiversity seeks to acknowledge the richness and complexity of human nature and of the human brain. The concept of neurodiversity gives us a context for understanding why we are so frequently delighted with Calvin's ADHD behavior in the Calvin & Hobbes comic strip, amused by Tony Shalhoub's obsessive-compulsive detective on the TV show Monk, and inspired by Russell Crowe's performance as Nobel Prize winner John Nash (who has schizophrenia) in the movie A Brilliant Mind.

The implications of neurodiversity for education are enormous. Both regular and special education educators have an opportunity to step out of the box and embrace an entirely new trend in thinking about human diversity. Rather than putting kids into separate disability categories and using outmoded tools and language to work with them, educators can use tools and language inspired by the ecology movement to differentiate learning and help kids succeed in the classroom. Until now, the metaphor most often used to describe the brain has been a computer or some other type of machine. But the human brain isn't hardware or software; it's wetware. The more we study the brain, the more we understand that it functions less like a computer and more like an ecosystem. The work of Nobel Prize–winning biologist Gerald Edelman supports this view (see, for example, Edelman, 1987, 1998). Edelman wrote, "The brain is in no sense like any kind of instruction machine, like a computer. Each individual's brain is more like a unique rainforest, teeming with growth, decay, competition, diversity, and selection" (quoted in Cornwell, 2007). In fact, the term brainforest may serve as an excellent metaphor when discussing how the brain responds to trauma by redirecting growth along alternative neurological pathways, and in explaining how genetic "flaws" may bring with them advantages as well disadvantages. Disorders such as autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and learning disabilities have been in the gene pool for a long time. There must be a reason why they're still there. As we'll see in the course of this book, the work of evolutionary psychologists represents a key component in exploring this fascinating question.

The use of ecological metaphors suggests an approach to teaching as well. After all, regular classroom teachers are far more likely to want a "rare and beautiful flower" in their classroom than a "broken," "damaged," or "problem" child. Just as we accept that individual species of plants have specific environmental needs (e.g., sun, soil, water), we need to understand that neurodiverse children require unique ecological nutrients in order to blossom. Teachers should not seek to "cure," "fix," "repair," "remediate," or even "ameliorate" a child's "disability." In this old model, kids are either made to approximate the norm (especially for national accountability tests) or helped to cope with their differences as best they can (the cliché that students can learn to live successful and productive lives "despite" their "disabilities" comes to mind here). Instead, teachers should seek to discover students' unique requirements for optimal growth, and then implement differentiated strategies to help them bloom.

Positive Niche Construction

In the neurodiversity model, there is no "normal" brain sitting in a vat somewhere at the Smithsonian or National Institutes of Health to which all other brains must be compared. Instead, there are a wide diversity of brains populating this world. The neurodiversity-inspired educator will have a deep respect for each child's unique brain and seek to create the best differentiated learning environment within which it can thrive. This practice of differentiating instruction for the neurodiverse brain will be referred to in the course of this book as positive niche construction.

In the field of biology, the term niche construction is used to describe an emerging phenomenon in the understanding of human evolution. Since the days of Darwin, scientists have emphasized the importance of natural selection in evolution—the process whereby organisms better adapted to their environment tend to survive and produce more offspring. In natural selection, the environment represents a static entity to which a species must either adapt or fail to adapt. In niche construction, however, the species acts directly upon the environment to change it, thereby creating more favorable conditions for its survival and the passing on of its genes. Scientists now say that niche construction may be every bit as important for survival as natural selection (Lewontin, 2010; Odling-Smee, Laland, & Feldman, 2003).

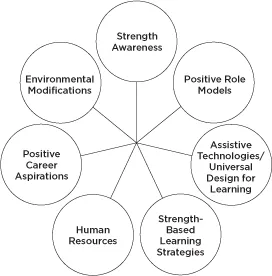

We see many examples of niche construction in nature: a beaver building a dam, bees creating a hive, a spider spinning a web, a bird building a nest. All of these creatures are changing their immediate environment in order to ensure their survival. Essentially, they're creating their own version of a "least restrictive environment." In this book, I present seven basic components of positive niche construction to help teachers differentiate instruction for students with special needs (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Components of Positive Niche Construction

Strength Awareness

If our only knowledge about students with special needs is limited to the negatives in their lives—low test scores, low grades, negative behavior reports, and deficit-oriented diagnostic labels—then our ability to differentiate learning effectively is significantly restricted.

Research suggests that teacher expectations powerfully influence student outcomes—a phenomenon that has been variously described as "the Pygmalion effect," "the Hawthorne effect," "the halo effect," and the "placebo effect" (see, for example, Rosenthal & Jacobson, 2003; Weinstein, 2004). As Paugh and Dudley-Marling (2011) note, "'deficit' constructions of learners and learning continue to dominate how students are viewed, how school environments are organized, and how assessment and instruction are implemented" (p. 819).

Perhaps the most important tool we can use to help build a positive niche for the neurodiverse brain is our own rich understanding of each student's strengths. The positive expectations that we carry around with us help to enrich a student's "life space," to use psychologist Kurt Lewin's (1997) term. Educators practicing positive niche construction should become well-versed in a range of strength-based models of learning, including Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences (Armstrong, 2009; Gardner, 1993), the Search Institute's Developmental Assets framework (Benson, 1997), Clifton Strengths Finder (Gallup Youth Development Specialists, 2007), the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Myers, 1995), and Dunn and Dunn's learning style approach (Dunn & Dunn, 1992). Educators ought to know what students in special education are passionate about—what their interests, goals, hopes, and aspirations are. Studies suggest that children who have the capacity to surmount adversity usually have at least one adult in their lives who believes in them and sees the best in them (Brooks & Goldstein, 2001). (See Figure 7.2 in Chapter 7 for a 165-item Neurodiversity Strengths Checklist to use in creating a positive mindset about a student with special needs.)

Example of poor niche construction: Eldon has just been diagnosed as having ADHD and an emotional disorder. In the teacher's lounge, teachers trade stories about his temper tantrums and his failure to comply with school rules. He has been observed commenting to his peers, "I've just been transferred to the retarded class. I guess that means I'm a retard, too." Other students refer to him as a "loser," a "troublemaker," and a "bully."

Example of positive niche construction: Ronell has ADHD and an emotional disorder. He also has been recognized as having leadership capabilities in his gang affiliations, good visual-spatial skills (he enjoys working with his hands), and an interest in hip-hop music. Teachers and students have been instructed to look for Ronell's positive behaviors during the school day and share them with him. Ronell has been informed of his profile of multiple intelligences (high interpersonal, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, and musical intelligences) and has been observed commenting to his peers, "I guess I'm good at a few things, after all."

Positive Role Models

Children are powerfully influenced by the adults they see in their daily lives. Social learning theory tells us that behavior modeling by adults provides children with one of the major building blocks they require for constructing complex behaviors in life (Bandura, 1986). Scientists suggest that this may be due to the existence of "mirror neurons"—brain cells that fire not only when we do something, but also when we observe others doing t...