Five Practices for Equity-Focused School Leadership

- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Five Practices for Equity-Focused School Leadership

About this book

This timely and essential book provides a comprehensive guide for school leaders who desire to engage their school communities in transformative systemic change. Sharon I. Radd, Gretchen Givens Generett, Mark Anthony Gooden, and George Theoharis offer five practices to increase educational equity and eliminate marginalization based on race, disability, socioeconomics, language, gender and sexual identity, and religion. For each dimension of diversity, the authors provide background information for understanding the current realities in schools and beyond, and they suggest "disruptive practices" to replace the status quo in order to achieve full inclusion and educational excellence for every child.

Assuming that leadership to create equity is a unique practice, the book offers* Clear explanations of foundational terms and concepts, such as equity, systemic inequity, paradigms and cognitive dissonance, and privilege;

* Specific recommendations for how to build support and sustainability by engaging colleagues and other stakeholders in constructive dialogues with multiple perspectives;

* Detailed descriptions of routines and roles for building effective equity-leadership teams;

* Guidelines and tools for performing an equity audit, including environmental scans;

* A change framework to skillfully transform your system; and

* Reflection activities for self-discovery, understanding, and personal and professional growth.

A call to action that is both passionate and practical, Five Practices for Equity-Focused School Leadership is an indispensable roadmap for educators undertaking the journey toward an education system that acknowledges and advances the worth and potential of all students.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Preparing for Equity:

The Ongoing Emotional and Intellectual Work of Equity Leadership

Preparing to Learn for Equity:

Key Concepts and Guiding Principles

DonaldDonald, a White male, was in his third year as superintendent of a midsized, first-ring suburban school district. Others saw him as an up-and-coming superintendent because he had declared himself to be a racial equity champion and had made "closing the achievement gap" the central goal of his superintendency. With his contract renewed for a second term, but with significant concern about a lack of progress on his equity goals, Donald directed his executive cabinet to complete an equity audit. In the process, he became aware of the incredible disproportionality in discipline rates between White students and students of color. Aware of how the suspension rate for African American males contributes to the "school-to-prison pipeline," he decided that the best course of action was to prohibit suspensions in the district's schools. After sharing this information with his leadership team, he convened a press conference to announce the policy change.SusanSusan, a White female, was a sixth-year principal in the district's most racially diverse middle school and had been leading with a clear focus on equity since her arrival. With several efforts producing positive results, she was concerned about this new policy. She knew that some of her fellow administrators were far too quick to issue harsh discipline to African American and other students of color. She was also aware that many other factors might be at play when students act in disruptive ways. She believed that her responsibility was to equip her staff with the tools and skills to effectively engage students in learning, build quality relationships with students and families, and manage behavior to support classroom learning goals.In the year following Donald's policy change, many schools became more chaotic, and learning outcomes decreased. In addition, conflict increased among school staff, administrators, and the community as many students felt unsafe at school and found their learning opportunities overshadowed by stressful and tumultuous interpersonal and behavioral interactions.At Susan's school, however, things continued to improve. She had strong relationships with her staff and the school community, founded on gathering input and collective decision making. To respond to Donald's policy change in ways that improved the community and the learning environment, Susan convened a series of conversations with students, staff, and families to discuss their concerns, values, needs, goals, and approaches to social, emotional, and behavioral learning at the school. Stakeholders identified what they needed to learn and do differently to reduce and eliminate suspensions. Topping their list were the following items: help teachers create stronger, more inclusive classroom communities; teach all school staff how to de-escalate tense situations in ways that maintain everyone's sense of dignity and belonging; agree on a set of grounding principles/values to guide all community members in their interactions with one another; create safe spaces and processes for supporting students when their emotions feel particularly intense; create accessible pathways to strengthen the relationships and communications between families and school staff; and adopt a restorative approach for responding to situations where someone has been harmed.The involvement of so many stakeholders in the process resulted in broad and deep engagement in implementing the plans they created. The process took a significant amount of time and the outcome was not perfect, but the school community continued to improve its approach to supporting students' development and sense of belonging, while also improving their learning.

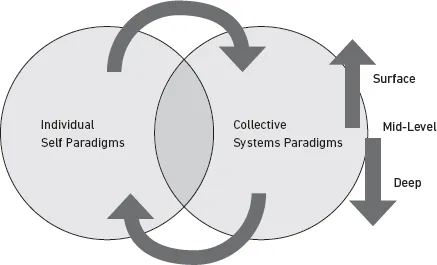

Paradigms and Cognitive Dissonance

Figure 3.1. Paradigms

Figure 3.2. Varying Paradigms Regarding Leadership, Equity, and Suspension from School

- If suspension patterns reveal racist tendencies, we must end suspensions.

- Suspensions are the problem.

- To be an equity champion, I need to take swift and decisive action to end this injustice.

- It's my job as superintendent to make this happen.

- I'm action-oriented; I can and will get this done.

- I will tell the principals to implement this at their schools and they will do what I say.

- Something has to happen to kids who act badly.

- Leaders are responsible for fixing problems.

- Rules and procedures fix problems.

- If suspension patterns reveal racist tendencies, we must do something to change them.

- This is a complex—not simple—problem.

- Although suspensions are a symptom, not the problem, they also create other problems.

- It's my job as principal to take this on.

- Our stakeholders will know what to do.

- The way to find and enact a solution is to involve those who are closest to the problem.

- The way to make this happen is for me to decide.

- People need to do what I tell them to do; it's their obligation as my employees.

- Taking quick and decisive action will bolster my credibility and reputation as an equity champion.

- Kids who act out should be punished.

- Fast, simple solutions are needed and sufficient.

- The system is fair; rules and consequences are applied evenly.

- I don't have the answers; we have the answers.

- You can't assume that simple solutions will solve complex problems.

- I can, should, and will make important decisions.

- Others' input and involvement is rarely needed and might get in the way of doing what I know needs to be done.

- Unequal outcomes are OK as long as White kids don't come out on the losing end.

- When faced with important decisions that will significantly impact others, my job is to gather people together and facilitate a process through which we collectively come up with a solution.

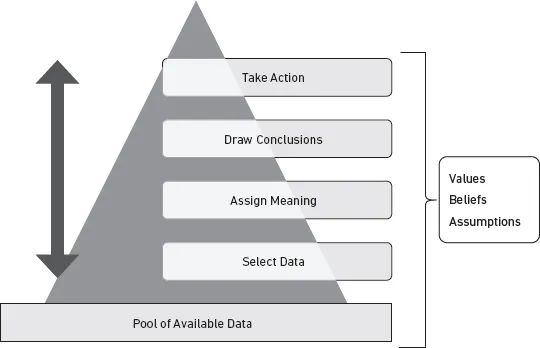

The Ladder of Inference

Figure 3.3. Ladder of Inference

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Practice I. Prioritizing Equity Leadership: Adopting a Transformative Approach

- Practice II. Preparing for Equity: The Ongoing Emotional and Intellectual Work of Equity Leadership

- Practice III. Developing Equity Leadership Teams: Essentials for Leading Toward Equity Together

- Practice IV. Building Equity-Focused Systems: Identifying Needs and Planning Systemic Change

- Practice V. Sustaining Equity: Preparing for the Long Haul

- Conclusion: A Final Word

- Appendix A. Sample Equity Audit

- Appendix B. Tools for Environmental Scans

- References

- About the Authors

- Related ASCD Resources

- Copyright