![]()

Chapter 1

Punitive or Restorative: The Choice Is Yours

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A colleague of ours once projected the following quote, widely attributed to Frederick Douglass, onto a screen at the start of a professional development session:

It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.

She then asked the assembled faculty to write down their own reactions to the statement and discuss them in small groups. The reactions our colleague heard were both positive and predictable: a lot of talk about the influence of students' family, school climate, and a sense of connectedness within the school on academic achievement.

When the conversations drew to a close, our colleague shared the school's discipline data from the previous year, which showed that suspensions occurred at rates disproportionate to the student population. In a majority of cases, the most serious offense was identified as defiance—a nonviolent act, and one that is broad and vaguely defined. This is not an uncommon finding: According to a report of suspensions in California schools, 34 percent of suspended students were punished for defiance or disruption (Losen, Martinez, & Okelola, 2014). Our administrator friend had calculated the number of instructional days lost to suspensions and provided comparative data on the grade point averages of suspended students versus those who had never been suspended. She then asked the faculty whether they were building strong children or ensuring that their communities will have future broken adults in need of repair. The frank 30-minute discussion that ensued inspired the school's staff to create a culture in which restorative practices could thrive. Over countless department meetings and informal exchanges, the staff performed yeomen's work analyzing and redefining classroom and schoolwide practices.

Our own experience has been that while our collective hearts as educators are in the right place, we tend to make decisions based on past experience. After all, we began our on-the-job training as teachers when we were five years old. Our beliefs about school, classroom management, and discipline have been shaped by decades of experience, starting in kindergarten. What we need is an effective classroom-management system—one that we can hold onto in times of stress and strife.

Effective Classroom Management

The term classroom management is confusing and misleading, mainly because it has no clear and widely agreed-upon definition. For some, the term refers to general control of students; for others, it refers to discipline procedures; for others still, it refers to both routines and procedures. Up until recently, we have avoided using the term, but we finally came across a definition we could stand behind: Cassetta and Sawyer (2013) define classroom management as being "about building relationships with students and teaching social skills along with academic skills" (p. 16), and we couldn't agree more.

There are two aspects of an effective learning environment (and, by extension, successful classroom management): relationships (specifically, the range of interpersonal skills necessary to maintain healthy relationships) and high-quality instruction. When students have strong, trusting relationships both with the adults in the school and with their peers, and when their lessons are interesting and relevant, it's harder for them to misbehave.

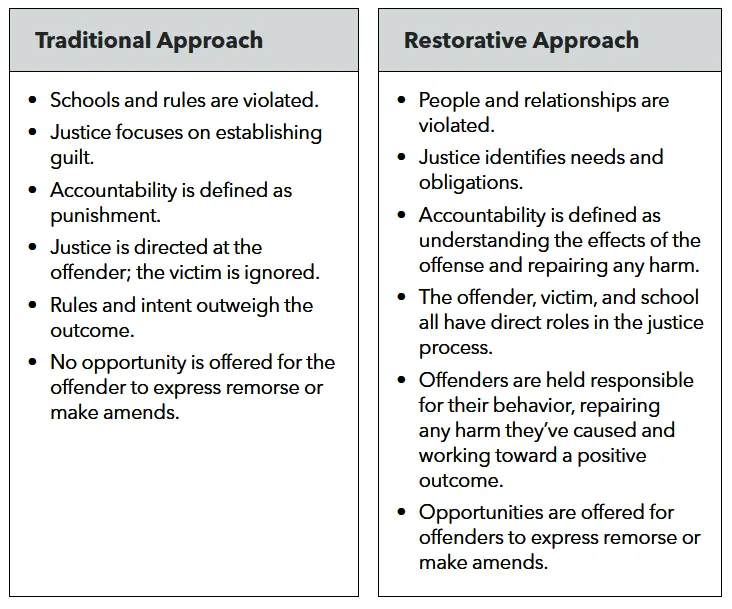

We don't expect an effective classroom-management system to eliminate all problematic behavior any more than we expect a new set of standards to raise all students' scores by leaps and bounds on the first try. Students are going to misbehave as they learn and grow—it's how we respond to their misbehavior that matters. We believe that students should have a chance to learn from their mistakes and to restore any damaged relationships with others. Our view is known as the restorative approach to discipline. The table in Figure 1.1, developed by the San Francisco Unified School District, illustrates the differences between the restorative approach and the traditional approach to discipline.

Figure 1.1 Traditional Versus Restorative Approach to Discipline

Source: Adapted from San Francisco Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative practices whole-school implementation guide (p. 19). San Francisco, CA: Author.

The Restorative Practices Movement in Schools

In its contemporary incarnation, the restorative practices movement is an offshoot of the restorative justice model used by courts and law-enforcement agencies around the world. In the restorative justice model, mutually consenting victims and offenders meet so that the former can be given a voice and the latter can have an opportunity to make amends. Importantly, this approach empowers a community to take an active role in resolving problems. Cultures throughout the world employ restorative justice to create peace among adversaries, ensure restitution, and make decisions at times of community crisis.

Restorative practices in schools cast a wider net than restorative justice in the courts. Whereas justice is by its nature reactive, restorative practices also include preventive measures designed to build skills and capacity in students as well as adults.

Restorative practices are predicated on the positive relationships that students and adults have with one another. Simply said, it's harder for students to act defiantly or disrespectfully toward adults who clearly care about them and their future. Healthy and productive relationships between and among students and staff facilitate a positive school climate and learning environment. In the restorative approach, when relationships in the school become damaged, the parties involved are encouraged to engage in reflective conversations that help offenders understand the harm that their actions caused and provide them with opportunities to make amends. As we describe further in this book, there are a number of ways to build relationships and create healthy learning communities.

Circles. Teachers in the restorative practices movement promote a sense of family in the classroom by having students sit in circles to discuss both curriculum-related topics (e.g., the role of genocide and war in a World History class) and noncurricular issues that bear discussing (e.g., how students might manage stress on the eve of a major state exam).

Individual conferences to address problematic behavior. We'll explore the details of these high-stakes meetings in greater detail further in the book, but for now know that restorative practices are not about letting things go or ignoring when harm has been done. Individual conferences require intense preparation on the part of the victim(s), the perpetrator(s), witnesses to the conflict, and anyone else who's been affected by it. In some cases, conferences involve two sets of parents or guardians who are very much at odds with each other: it's common for the offender's family to lobby for mercy and for the victim's family to demand retribution. To ensure that conferences run smoothly, it is crucial to engage with families preventively, before crises occur.

The criminal justice system. In a small number of cases, the criminal justice system will play an important part in a restorative approach to student discipline. We have found that strong ties to our local police department and juvenile justice system have enhanced our ability to play a meaningful role in the lives of adjudicated youth, allowing us to partner with families and the courts to positively affect students' lives. In fact, many youth court systems follow the restorative approach to justice, which mandates therapeutic interventions over retributive ones. We have personally been fortunate to work with skilled police and youth probation officers who have received formal training in restorative practices.

Teaching Rather than Punishing

Traditional school discipline practices are considered separate from the academic mission of the school. By contrast, restorative practices are interwoven into every interaction in the building. At your school, is a specific administrator assigned to disciplinary matters? This might be the principal, vice principal, or dean of students. Ask a few students at your school, "Where do kids go when they misbehave?" If you keep hearing a specific person's name—or worse, a specific practice (e.g., "Kids go home 'cause they get suspended")—then you know that your school is pursuing a traditional approach to discipline. If this is the case, it's time for a change.

It's far too common in schools for educators to wait for discipline problems to emerge and then handle them on a case-by-case basis. Such an approach leaves adults exhausted and children with limited skills development. We don't leave the acquisition of reading or mathematics skills to chance; we engage in explicit, systematic, and intentional instruction to ensure that learners progress academically. So why wouldn't we do the same to ensure that students progress socially and emotionally? The social and emotional development of students is often poorly articulated in schools—relegated to an assembly and a few accompanying lessons. Traditional tools for addressing behavioral issues among students—rewards and consequences, shame and humiliation, suspensions and expulsions—run counter to a restorative culture and do not result in lasting change, much less a productive learning environment.

Rewards and Consequences Don't Work

Right now you may be thinking to yourself: I've got a whole list of rewards and consequences in place to manage behavior. To be sure, nearly every classroom-management book will have a section devoted to the use of rewards and consequences. But there's one problem: Rewards and consequences don't work—or at least, they don't teach. They may result in short-term changes, but in reality they promote compliance and little else.

Rewards

You may be thinking to yourself: I don't use punishments. My students earn points and privileges for good behavior. Some people think that bribing students with an ice-cream social or a movie day when they behave is somehow better than meting out consequences when they don't. In reality, rewards and consequences are two sides of the same coin: both are attempts to control students' behavior rather than teach them how to engage in productive learning. Tangible rewards have actually been shown to undermine motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 2001). Rewards suggest to people that they are being compensated for engaging in an unpleasant obligation. Importantly, research shows that good behavior diminishes as rewards are phased out. According to Kohn (2010), "Scores of studies have confirmed that rewards tend to lead people to lose interest in whatever they had to do to snag them. This principle has been replicated with many different populations (across genders, ages, and nationalities) and with a variety of tasks as well as different kinds of inducements (money, As, food, and praise, to name four)" (p. 17). Because students begin to lose interest with what they're doing, over time the number or value of the rewards offered to them must increase if they are to remain on task.

Consequences

Why do we punish students by meting out "consequences" when they misbehave? Probably because we experienced punishment as students ourselves. The most common punishment for student misbehavior in elementary school is loss of recess (Moberly, Waddle, & Duff, 2005)—ironic, given that evidence has shown regular physical activity to reduce problematic behavior and increase student achievement (Ratey, 2008). Another common punishment: placing students' names on a board and applying checkmarks by those of students who've misbehaved. Such attempts to hold students publicly accountable for their behavior can render them compliant but can also make them feel anger, humiliation, and a range of other negative emotions that serve to shut down learning (Woolfolk Hoy & Weinstein, 2006).

Taking things away from students in the name of improving their behavior and learning can actually do the exact opposite. Can you imagine if we did the same in an attempt to improve faculty behavior? What if you had to stay 10 minutes after work because you talked during a staff meeting? What if your name were singled out on a chart for turning your grades in late? Consider the range of emotions these actions would evoke in you—and realize that children feel these emotions, too.

Nancy remembers her first year teaching elementary school. She had taken a classroom-management course as part of her teacher-preparation program, written papers about her philosophy of teaching, and investigated various different management systems. In her student-teaching class, for example, she observed a "stoplight" classroom-management system in which students' names were written on slips of paper and placed in color-coded card stock pockets: green for good behavior, yellow for behavior that had led to a warning, and red for misbehavior that needed to be addressed. When Nancy was hired for her first teaching position, she adopted a similar practice: labeling clothespins with students' names and moving them along a cardboard continuum that ranged from "Outstanding" to "Office." However, it soon became apparent to Nancy that moving clothespins all day long consumed a lot of time that she could otherwise devote to teaching. What's more, the clothespin system had led to little change in her students' behavior; in fact, the children lost interest in the system—and, soon after, in learning. Instead of fewer challenging behaviors, Nancy seemed to be dealing with more.

Maybe it's just not the right system, she thought. As a new teacher, she was granted release time to observe teachers at work in other classrooms, so she decided to visit the room of a veteran kindergarten teacher known around the school for her kindness and gentle nature. On observation, however, Nancy found that the teacher's classroom-management system belied her reputation. At the beginning of the school year, she had invited her students to bring their favorite stuffed animals with them to keep in class. The stuffed animals were displayed on a shelf, each one labeled with the name of its owner. Whenever students misbehaved, they were to walk to the shelf and turn their stuffed animals around to face the wall. The looks on students' faces after doing this displayed heartbreaking sadness and anger.

Nancy removed the clothespins from her classroom the very next day. She also got rid of the time-out chair. It had dawned on her that the "consequences" she was meting out were actually punishments—and punishments don't teach, they just create more distance between teachers and students. Punishments rely on our ability as adults to leverage an unequal power relationship over children; it puts children in their places by reminding them who's really in charge. Students who are punished will come up with a list of reasons why they are the victims and will channel their negative emotion toward those doing the punishing. Instead of reflecting on their behavior or making amends, they will plot how to avoid detection the next time. As Toner (1986) notes, punishment thwarts the development of empathy in children, who learn instead to look out for themselves regardless of their effects on others. Most troubling of all, punished children learn from adult examples that exerting power is the way for them to get what they want—a notion diametrically opposed to the social and emotional well-being we are trying to foster.

A Different Way Forward

It took several years, but Nancy eventually developed new tools to use with students when their behavior proved problematic. She began to spend more time establishing and teaching rules and setting expectations, structuring conversations with students that strengthened relationships and helped develop communication skills, and learning new ways to de-escalate disruptive events. Most importantly, she learned (and continues to learn) that problematic behaviors signal a student's lack of skills for responding appropriately to difficult situations. Just as students need teachers to teach them grammar and math, they need us to teach them how to respond properly to events.

Children who are habitually criticized, humiliated, or shamed internalize negative feelings about themselves that hinder their healthy development. By contrast, children accustomed to loving support and guidance are much more likely to become healthy and productive citizens. The traditional consequences-and-rewards system of discipline common in many classrooms is not resulting in children who are prepared to learn.

Let's be clear: we're not saying that teachers should completely refrain from rewarding students—just that the rewards should not be contingent on students' behavior. These types of rewards fall under the rubric of "noncontingent reinforcement" (Cipani & Schock, 2010). It's fine to offer rewards "just because," regardless of whether students "deserve" them or not. In fact, noncontingent reinforcement can actually help to prevent problematic...