![]()

Chapter 1

Why Place Matters

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"My experience with place-based education prepared me to thrive in every aspect of my being," said high school student Elizabeth Irvin (2018, para. 6), after CITYterm, an immersive project-based learning experience in New York City. It combines city expeditions with seminars and meetings with politicians, artists, urban planners, and authors.

Irvin said the six-day experience uncovered new academic interests that she may pursue as a career. She added, "Discovering my passion for alternative learning styles has played a large role in my college search" (2018, para. 6).

The experiences that shape our lives almost always include relationships—with someone who walked alongside us, someone who expanded our horizons, someone who inspired us. In addition to people, shaping experiences are often connected to places—a gallery, theater, workplace, soccer pitch, clearing in the woods, or mountain trail. Sometimes that shaping place is at school, but the thesis of this book is that the entire community is a classroom worth connecting with and that place is an integral component of youth development.

This chapter addresses three questions: What does place do uniquely well? Doesn’t technology make place irrelevant? Why is place important now?

The following sections make the case that place is important, relevant, and timely. More specifically, place promotes agency, equity, and community; it provides a compelling context for learning; and it is bolstered by current trends in practice, policy, and technology.

Place Promotes Agency, Equity, and Community

Context matters. Although time spent in the community or on a trip to another community seems academically "expensive," place is uniquely efficient at delivering value to young people and the places they engage with. Every community and place has a unique ethos, ecosystem, and combination of assets and challenges. Connecting young learners to their community and enabling them to immerse in other communities near and far promotes the foundational goals of public education: agency, equity, and community. Engaging young people in exploring place stands to benefit us all.

Agency

Marie Bjerede progressed from an engineer to a high-tech general manager because she had great technical skills and the ability to communicate and collaborate. Leading Qualcomm’s Design Center, she studied human motivation and became an early advocate of self-organizing teams. Bjerede found that in attacking adaptive problems, it was creativity and collaboration that mattered. The most successful engineers didn’t wait to be told what to do; they understood the goals and took initiative. It’s this sense of agency—the ability to act on the world—that, according to Bjerede, will be the most important employment skill. It’s a confidence that we can affect our future and our surroundings (Getting Smart Staff, 2018a, para. 3).

Agency requires self-knowledge, social awareness, and a sense of place and time. It is an applied disposition gathered through successively larger actions on a progressively larger world. What teaches us to perceive our location and relations is not language; it is our physical senses collecting action research. Agency is a muscle; place-based learning is the gym.

Many schools value routine and compliance—and both squelch student agency. It’s extended encounters with novelty and complexity that build the disposition and skills of agency—the humility to appreciate the complex and the confidence to know what to do next. These valuable extended challenges are frequently connected to a community that provides context for learning and opportunities for contribution. Once students feel ownership in a space and feel valued, agency can begin to develop through these powerful learning experiences.

Equity

At the core of place-based education is the need for more equitable learning environments for all students—environments where students are seen, valued, and heard. In these environments, learning is designed with and for students as humans and individuals in the space. This is deep and complex work, but it should be at the core of why we choose to work with young people. Utilizing place is one way to do this.

Young people from affluent households often experience a rich variety of places both locally and internationally that are not easily accessible to those less fortunate. A school’s systematic commitment to expose children to a variety of community assets closes a portion of this opportunity gap. An example is a commitment by the city of Tacoma, Washington, to allow every preschooler in the city to spend a week learning at the zoo.

People who grew up experiencing racism or intolerance may feel like something—and some place—has been taken from them. Beyond providing access, community learning experiences can create enfranchisement—the sense that "people like me" belong here, whether that’s at the zoo, a museum, city hall, or a high-tech workplace.

Each learner is unique, and equity demands that we meet every child where he or she is—emotionally, cognitively, economically, and geographically. Connecting learners to the place where they live can contribute to a sense of identity—a sense of who they are and where they’re from. The humblest settings and surroundings have something to teach. And learning about a new place may be the best way to illustrate and support the variability in the way humans perceive and process an experience.

We cannot assume that everyone has the same access to opportunities and networks (Fisher & Fisher, 2018). By engaging students in place, we increase their ability to have meaningful experiences and build social capital (see page 12 for more details). Work-based learning and community service are examples of experiences that extend social networks and may expand future opportunities.

Place-based experiences can directly confront factors that have been oppressive or limiting for communities. For example, Vaux High School is a partnership between the School District of Philadelphia, the housing authority, the teacher’s union, and Big Picture Learning. Students engage in extensive internships and benefit from on-site partners that provide youth and family services (Vander Ark, 2018d). "We created a place kids want to be. We created ownerships through internships," said executive director David Bromley (Vander Ark, 2018d, para. 9).

Community

Place-based education connects learning to communities and the world around us; it builds community in four respects:

- It creates bonds. When a group experiences the wonder of a vaulted ceiling, mountain vista, or night sky, it creates a special bond. Whether it’s the challenge of navigating a subway or trailblazing in the woods together, these moments of shared struggle or awe can act as a glue that connects people and builds community. Early childhood education environments often use community as the basis for teaching and learning throughout the year, grounding each experience in how we can work together and create common norms and culture.

- It personalizes learning. Place-based learning allows students to find a personal connection to their community or a place. With some voice and choice in shaping projects, internships, and service experiences, learning is personal and community connected.

- It builds social capital. With intentionality, place-based learning helps young people develop their social networks and take the chance out of chance encounters beyond school.

Julia Freeland-Fisher, director of education at the Clayton Christensen Institute, became interested in social capital after learning that more than half of all job placements result from a personal connection—and that schools just aren’t set up to influence this critical success factor. She notes that schools may be social, but most are insular. Imagine the community that could be created if, through a series of internships, site visits, and community-connected projects, each high school graduate left school connected with 100 community leaders or professionals—locally and regionally.

- It promotes contribution. Some schools treat students as participants preparing for a distant future. Place-based learning helps young people identify opportunities and make community contributions in the present—powered by new technologies that make it easier than ever to code an application, launch a campaign, or start a business. When empowered with a sense of agency and supported with time and tools, young people can contribute to their community in unprecedented ways.

With repeated place-based experiences, young people are cocreating the future. In a world that is becoming more individualistic, place-based learning invites young people into the community. Learning in a variety of places with a wide range of people builds agency, equity, and community.

Place Provides a Compelling Context for Learning

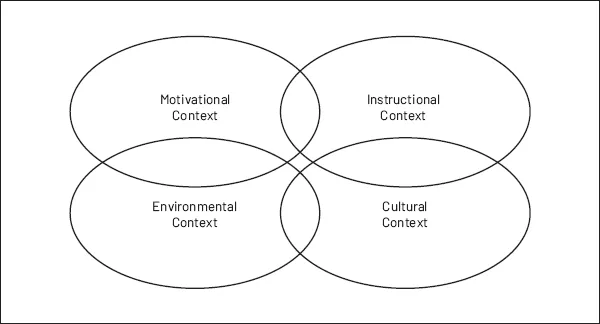

With a global economy and technology that connects almost everyone and extends learning and work opportunities, one could ask, "Isn’t place less relevant?" In fact, community-connected learning is more relevant than ever because it offers a unique context for learning through four dimensions: motivational, instructional, environmental, and cultural (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Context and Place-Based Learning

Place-based learning promotes agency, equity, and community by offering a compelling context with four dimensions.

Place Is a Motivational Context

Think of your most memorable learning experience. It might have been in school—an experiment or a writing assignment—but chances are it was extracurricular or out of the ordinary. It was probably rooted in relationships and involved an authentic challenge. It may have been associated with a place.

Places have the ability to create a sense of awe and wonder—as might occur in a great hall for a musical performance, when viewing a mountain vista, or in the boundary spaces between sea and land. Places can also provoke anger and concern—for example, a polluted stream, the site of an obvious injustice, or a location marred by a dangerous condition—that, in turn, may promote study and action.

Moments of awe or anger, coupled with student-led inquiry, can fuel meaningful, deeper learning. Our inherited school structures tend to squeeze out place-based experiences (which are more common in the primary years) with a focus on content transfer. The cumulative effect of well-intentioned efforts has led to less focus on the outcomes that matter most and the experiences most likely to deliver them.

Place Is an Instructional Context

For teachers at High Tech High in San Diego, California, place is the palette and the city is the text. Students in the High Tech High network (four campuses total) benefit from museum partnerships, watershed studies, community-connected impact projects, and business partnerships (Liebtag, 2019).

The 200 schools that belong to the nationwide New Tech Network (90 percent of which are district schools) share outcomes that matter, teaching that engages, culture that empowers, and technology that enables. New Tech students participate in project-based and place-based learning experiences that leverage partnerships and community assets to make learning authentic and meaningful (Vander Ark, 2017). Teachers in New Tech schools engage in place-based learning including site visits and walking tours (McBride, 2016).

Whittle School and Studios is a global school network. Initial host cities of Washington, D.C., and Shenzhen, China, comprise a platform for understanding how communities work, for integrating classroom learning with the life of the world, for addressing global challenges, and for cultivating the awareness to become socially responsible global citizens. Whittle campuses have a weekly Expeditionary Day when students engage with questions from their peers or of their own design, both by working outside the classroom within the larger school community and by engaging the people, places, politics, and peculiarities of their city. Students can study at other Whittle campuses, each with their own Center of Excellence, with a theme based on local strengths (Getting Smart Staff, 2018b).

The Place Network is a collaborative network of rural schools that connect learning and communities to increase student engagement, academic outcomes, and community impact. They share an integrated project-based approach to community-connected learning.

These four school networks and many others believe that project-based learning is an effective way to build student agency, persistence, and project management skills and to apply communication and problem-solving skills. Many projects are community connected and use place as an instructional context.

Place-based learning uses the city or town as the classroom. It leverages local assets and partners in learning and connects local issues to global themes. It situates extended integrated challenges in a local ecosystem.

Place Is an Environmental Context

We live on a complicated planet—one that humans are just beginning to understand but increasingly influence. The Fourth U.S. Climate Report indicates rapid (and predictably catastrophic) changes and a decline in the overall health of the environment. Recent years were the hottest on record, with more than the usual number of natural disasters, such as fires and tropical storms (Reidmiller et al., 2018, p. 37). It appears that young people will continue to experience more extreme weather and the unpredicted collisions of manmade and natural systems.

The combination of increasing natural and manmade shocks will damage regional economies—and perhaps the global economy. As a result, there is an increased need for more community connections, along with more agility and adaptability.

The State Education and Environment Roundtable (SEER) sponsors a network of schools around the Environment as an Integrating Context (EIC) model for improving student learning. Launched in 1995 with support from The Pew Charitable Trusts, more than 200 schools are involved in the network.

The interaction of humans, nature, and built communities is extraordinarily complex. It involves the economic, cultural, and ecological forces at work in a region. Young people deserve the owner’s manual for the place they are inheriting. That means studying place from all three vantage points.

Place Is a Cultural Context

Culture forms the foundation for behavioral norms—the unspoken rules of conduct and shared social conventions. Because culture matters to human development at the macroeconomic level and to identity development at the individual level, it is worth studying. Given the complexity of culture...