![]()

Chapter 1

Focus on Learning

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

These frustrated ramblings in a 7th grader's journal are all too familiar to most educators. Teachers spend time planning lessons, basing them on standards and guided by curricula and instructional materials, only to be met with resistance and apathy. We try to keep up with developments in instruction—you wouldn't be reading this book if you didn't—but the pieces often seem to remain disparate and not come together. Perhaps it's a matter of changing our focus. Have we considered what our lessons might look like from the other side of the desk?

As the authors of this book, we have looked at instruction in more than 17,000 elementary and secondary classrooms. During this experience, we have come to recognize the power of shifting the focus from teaching to learning. This realization has come both over time and in a few blinding moments of clarity.

A few years ago, we hosted our first annual Engagement Conference in Las Vegas. On the eve of that conference, like expectant parents, we carefully reviewed our plans for the following days, ensuring that every detail was covered. Finally, at about 10:30 p.m., John said, "I think we're ready, but you don't seem very happy."

"What's the ‘big idea’ for our conference?" Jim asked.

"That kids need to be more engaged… actively involved in learning activities."

"And how are we starting?"

"With your 90 minute keynote speech…"

And at that point, we both realized that wouldn't work. So, we set about designing a new conference opening—one in which participants would be physically and cognitively involved in the work. We were nervous, because we had never seen this kind of thing done in a large general session, but it gave rise to one of our favorite sayings: "Trust the learners."

A major purpose of this book is to help educators understand and develop this trust. Whether you are serving as a classroom teacher, site administrator, district leader, school board member, or parent, this idea can have powerful implications. In the following pages, we will share:

- What's really going on in classrooms around the country.

- Benchmarks to determine where your school is on the continuum of effective instruction.

- Good classroom practices for implementation and professional development.

- Tools and techniques to improve academic scores.

- Qualities that will result in students being more engaged.

- Strategies that develop higher-level thinking.

- Techniques to lead professional learning communities (PLCs) in a new, more thoughtful direction.

- A vision of what your school could be.

For many reasons—the movement to standards and accountability being chief among them—one might think that a shift toward learning-focused instruction should have already happened. Unfortunately, testing elevated the importance of results but not the learning process.

In a traditional classroom model, time is the constant and learning is the variable. That is, all students receive the same instruction for roughly the same amount of time. The results—not surprisingly—are a bell curve. Some students learn the content deeply and well, most have a moderate level of comprehension, and a few don't learn it at all. With the advent of standards, learning has become the desired constant, yet one of the most important variables—time—was never adjusted. Another element of the learning process resistant to change has been the traditional role of the teacher.

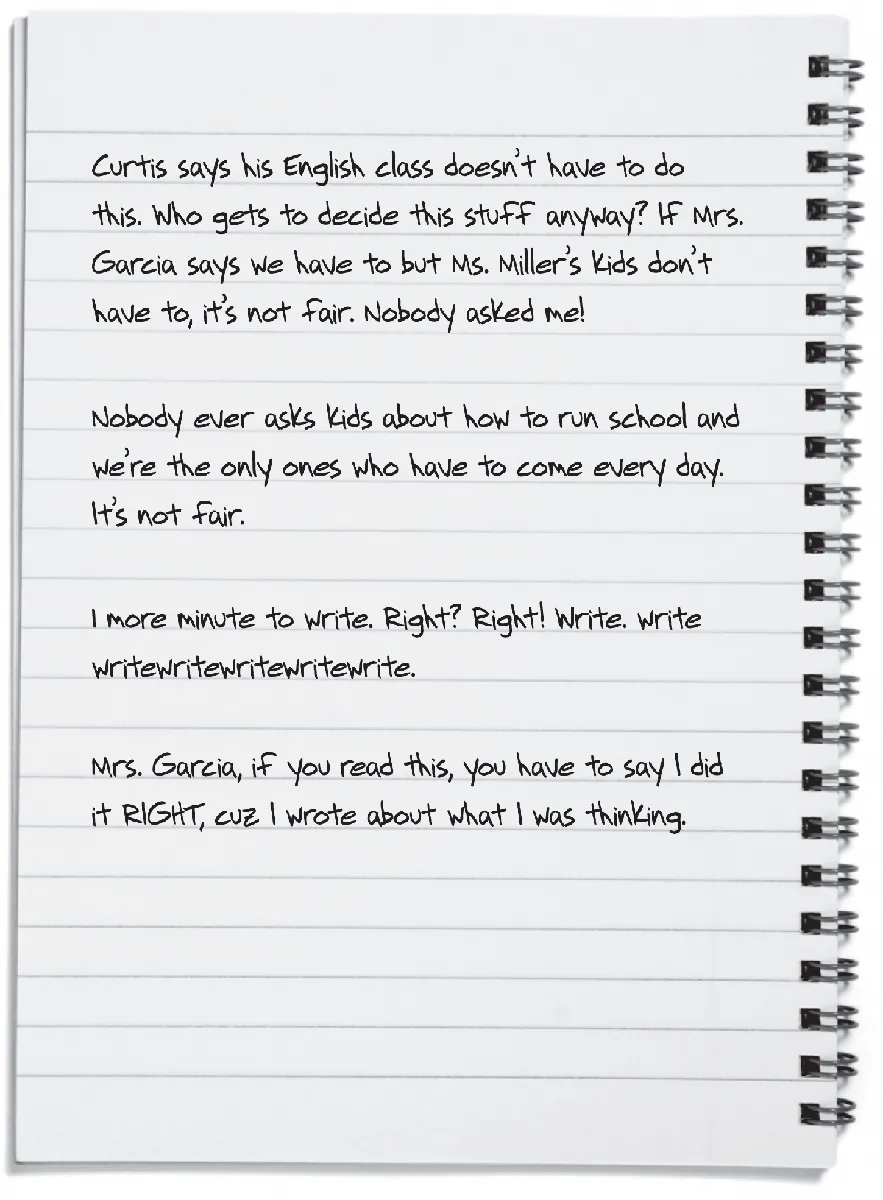

For more than 20 years, the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement has provided educators around the world with statistics regarding math and science achievement. In 1999, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) analyzed math classes in seven nations to examine the relationship between the cognitive demands of mathematical tasks and student achievement. In this study, a random sample of 100 8th grade math classes from each of the countries (Australia, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong [China], Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States) was videotaped during the school year. The six other countries were selected because each performed significantly higher than the United States on the TIMSS 1995 mathematics achievement test for 8th grade (Stigler & Hiebert, 2004).

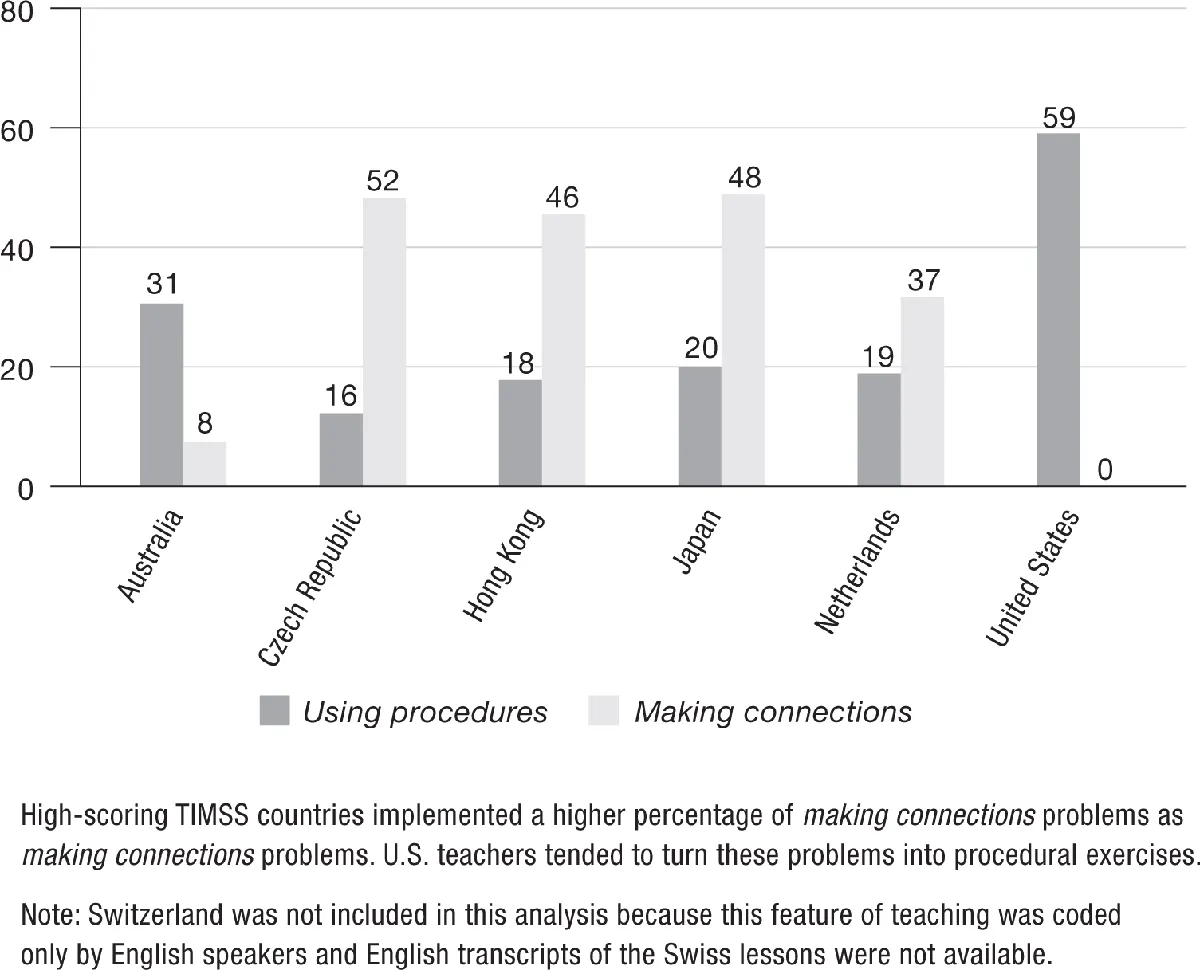

In the 1999 video study, the classroom math tasks were categorized as either using procedures (i.e., requiring basic computational skills and procedures) or making connections (i.e., focusing on concepts and connections among mathematical ideas). The problems were coded twice—once to characterize the type of math problem and once to describe its implementation in the classroom.

Figure 1.1 captures the percentage of each type of math problem presented in six of the seven countries.

Approximately 17 percent of the problem statements in the United States suggested a focus on mathematical connections or relationships. This percentage is within the range of several high-achieving countries (i.e., Hong Kong, Czech Republic, Australia).

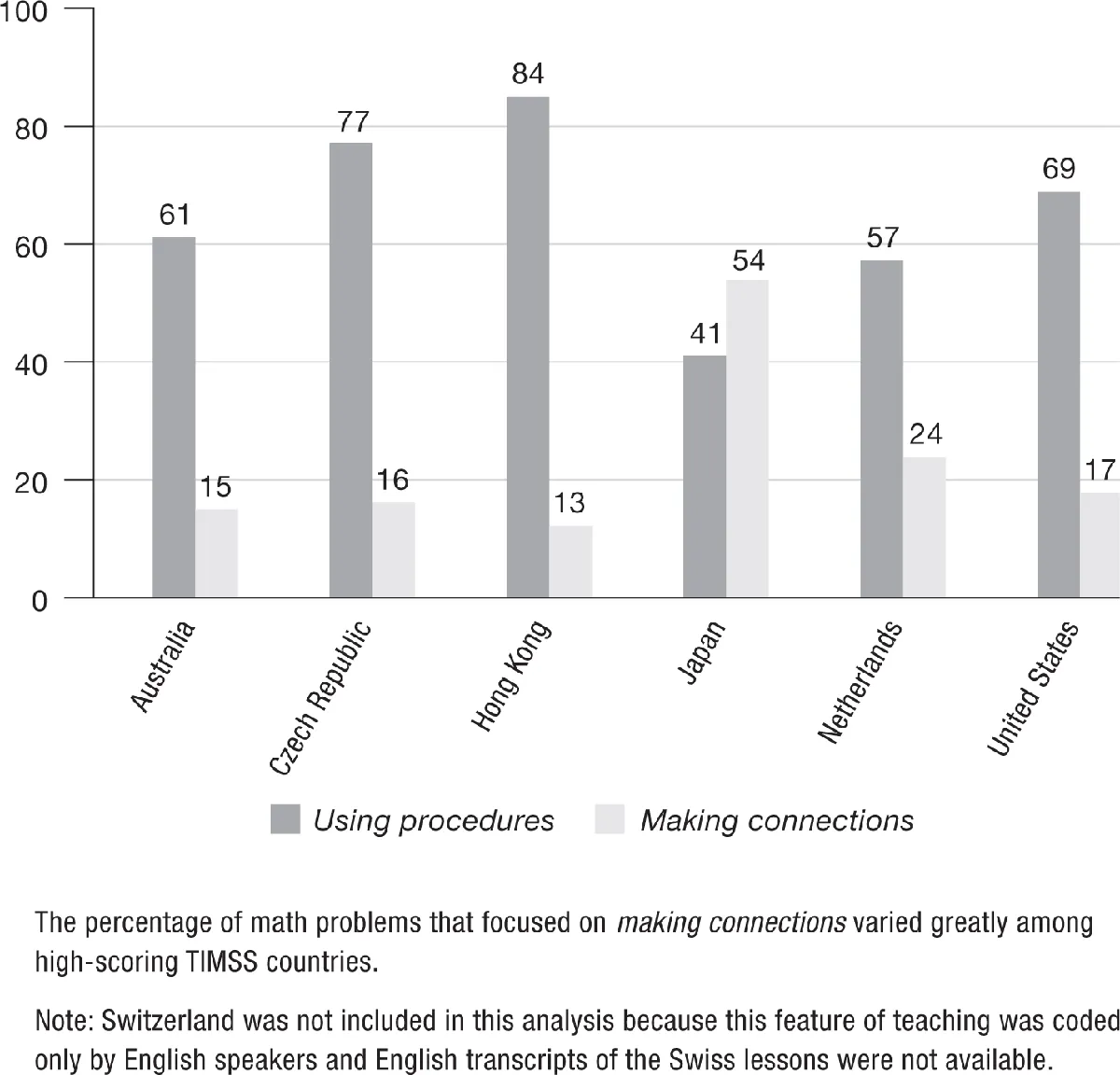

As students worked through the math problems, the video study analyzed teacher-student interactions and the mathematical approach taken to solve the problems. Figure 1.2 shows the coding of the student work as it was actually performed by students.

Though the curriculum may have involved a balance in the types of problems proposed, virtually none of the making connections problems observed in the United States were implemented in a way that guaranteed conceptualization or demanded mathematical connections be made by students. There are a number of issues highlighted by the study, but the most troubling finding of all is that teachers in the United States reduced most problems to procedural exercises or simply gave students the answers—efficient teaching perhaps, but ineffectual learning.

If the TIMSS video study had only looked at instructional delivery or the resulting achievement measures, these issues might not have been as obvious. Focusing on students during academic activities provided the greatest clarity into the achievement results.

Why does this disconnect between curriculum and implementation occur in the United States? Math teachers across the country have shared with us many valid reasons when we ask this very question:

Figure 1.1 | Types of Math Problems Presented

Source: From "Improving Mathematics Teaching," by J. W. Stigler and J. Hiebert, 2004, Educational Leadership, 61(15), p. 14. Copyright 2004 by ASCD. Reprinted with permission.

- "Our curriculum is too full, inviting coverage and speed over deep mathematical understanding."

- "The discomfort of letting our students struggle; the need to rescue our students and then move on."

- "The pressure of the ever-present high-stakes testing."

- "The fear that a visiting administrator who walks in during a moment of student struggle might not see the teacher ‘teaching.’"

- "It takes too long for them to figure it out."

This challenge remains today. Math teacher Dan Meyer put it into perspective when he said that we are "taking a compelling question, a compelling answer… but we are paving a smooth, straight path between the two and congratulating our students for how well they can step over the cracks on the way" (Meyer, 2013).

Figure 1.2 | How Teachers Implemented Making Connections Math Problems

Source: “Improving Mathematics Teaching,” by J. W. Stigler and J. Hiebert, 2004, Educational Leadership, 61(5), p. 15. Copyright 2004 by ASCD. Reprinted with permission.

The idea of a teaching-learning shift didn't spring into our minds fully formed. As you may have already gleaned, we had the opportunity to examine teaching and learning in a variety of classroom situations—more than 17,000 and counting. We conducted the vast majority of those visits through the classroom walkthrough process. It was in that environment that we first worked together and that our ideas about the teaching-learning shift became concrete.

In 2001, we were asked by a professional development company to help create one of the first classroom walkthough models. It became very popular, and we helped train thousands of educators across North America. In 2005, we decided to form our own organization, Colleagues on Call. To begin this new venture, we asked ourselves what we learned about classroom walkthroughs.

The answer, unsurprisingly, came from the teachers with whom we worked. They said, "We know your visits aren't supposed to be evaluative, but sometimes it still feels like evaluation." It didn't take long to figure out why teachers felt that way: we were looking in the wrong place. Most of the data gathered and feedback provided were based on teachers' behaviors. When the focus of the visits was shifted to students, the differences were dramatic. Suddenly, we had a data set that could be gathered in no other way. Instead of monitoring whether an objective was posted on the board, students were asked to explain what they were learning and why it was relevant. In this way, thinking levels could be viewed across content areas and grade levels. Whereas formal assessments provided post-instructional data, observations made during these walkthroughs provided teachers with real-time data they could use to make instructional decisions.

We call this process Look 2 Learning (L2L), and if you glance at the contents for this book, you will get a fairly accurate picture of what we look for—from the students' point of view—during our classroom visits.

Here's how it works: After two days of training, L2L team members (alone or in pairs) visit classrooms in their respective schools for two to four minutes. While there, they listen to conversations and interactions, look at student work, and talk to students. Information is collected on an electronic device or on paper. Over time, the data are aggregated so trends and patterns can be observed. This information is then shared with classroom teachers, who—through reflective conversations—determine which professional practices they might like to refine. L2L data can then be used to monitor progress. Adjustments can be made and celebrations scheduled—all based, of course, on the learning and not the teaching.

Several times in this book, we will mention the use of continua. We think they can be powerful organizers for graphically representing complex relationships and relative magnitudes. For the present discussion, a continuum can help depict the teaching-learning shift and the change in focus that happens with Look 2 Learning walkthroughs.

In general, a continuum shows a relationship of degree that is indicated by position from left to right. It might look something like this:

We can also make use of the vertical dimension. For instance, a point high above the line could indicate a behavior solidly in adult control, whereas one below the line could denote a significant level of student control.

Earlier, when we discussed the shift in focus brought about by Look 2 Learning walkthroughs, we mentioned learning objectives. Where on this continuum might we locate "The objective was written on the whiteboard"? First, think vertically; we can identify this as...