![]()

Part I

Understanding Motivation

![]()

Chapter 1

The Challenge of Motivating Students

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Engagement and motivation—what's the difference? Teachers everywhere strive to motivate their students and engage them in learning. Can we really motivate others, or is it a personal thing that happens when conditions are right? The English words motivation and movement are derived from the Latin movere, "to move." The German philosopher Schopenhauer (1999) suggested that motivation was the result of all organisms being in a position to "choose, seize and even seek out satisfaction." Neo-behaviorists Hull and Spence used terms such as drive and incentive as synonyms for motivational concepts.

Paul Thomas Young (1961) defined motivation as the process of generating actions, sustaining them, and regulating the activity.

Salamone (2010) suggests that motivation processes allow organisms to regulate their internal and external environment, seeking access to some stimuli and avoiding others. Sutherland and Oswald (2005) suggest that engagement is not just a simple reaction of a student to a teacher's action but is much more complex.

Although there are many definitions of motivation, with some stressing the notion of movement that would suggest engagement, we should not assume that motivation and engagement are synonymous. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably, but really motivation is the force or energy that results in engagement. In a classroom, the complex interaction of teacher, student, and curriculum helps to create motivation that yields high engagement.

Motivation, Drive, Tenacity, and Grit

Motivation, drive, tenacity, and grit are currently hot topics. A variety of opinions and theories are emerging from cognitive psychology about how important these skills are to one's success in life and how to promote them.

Self-Efficacy

Students arrive at school with an already well-developed self-image of competence or incompetence resulting from messages they have received at home since birth. Whether they have been encouraged to persevere when faced with challenges or coddled and discouraged from taking risks to overcome obstacles, students' beliefs about their abilities will affect their level of motivation and engagement. A learner's self-efficacy (one's belief in one's ability to succeed in specific situations) can greatly influence his or her motivation. In general, students with high self-efficacy are more likely to give more effort to complete a task and to persist longer than a student with low self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986). Their world-view of "never give up" and can-do attitude are essential to success.

Social beliefs related to gender or race also contribute to one's mindset about performance level. Gender bias messages or cultural cues may influence whether students feel capable or possibly doomed to failure (Aronson & Steele, 2005). These beliefs can be instrumental in helping to motivate discouraged learners.

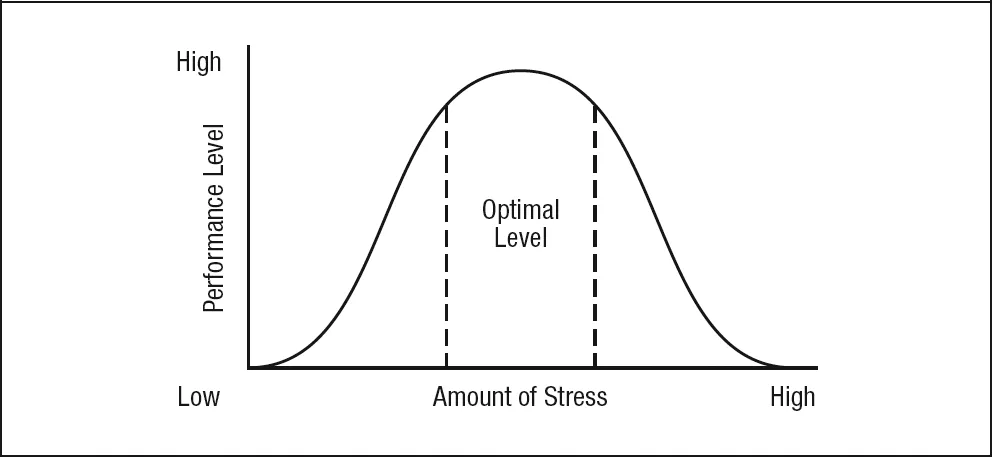

The Yerkes-Dodson Law of Arousal

Each of us reacts to a stimulus differently. For example, a project or task offered to a group of students will prompt a full range of responses related to motivation, from excitement to boredom. Students will react negatively or positively depending on how they perceive the difficulty of the task or the challenge involved and the interests they have. Their mindsets as to the probability of success will influence their excitement or frustration facing the task and thus, ultimately, their motivation.

The relationship between pressure (arousal) and one's performance is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law (Yerkes & Dodson, 2007). See Figure 1.1. As stress and pressure rise, performance usually improves. At the peak of the curve, one has reached "maximum cognitive efficiency" (Damasio, 2003). One's performance will not likely improve no matter how much additional pressure or stress is exerted. In fact, performance and motivation may begin to diminish if pressure continues. We can benefit from the endorphin rush that occurs when we increase our level of stimulation by pushing ourselves physically or mentally, but the apex of optimal performance is a tipping point. Like the Goldilocks theory, the Yerkes-Dodson law notes that in some cases there could be either too low or too intense an arousal. The ratio of stress to performance needs to be "just right" for each individual learner in order to maintain motivation.

FIGURE 1.1 Yerkes-Dodson Law of Arousal

We need to strive to provide the "just right" balance of excitement and challenge without undue stress for our students. Prior experience with similar tasks may influence one's reaction and degree of motivation. Tiered lessons and adjustable assignments (Gregory & Chapman, 2013) attempt to do this. So the trick is to find the optimum level of challenge that engages, and is enjoyable and safe for every learner (see the sections on flow and the zone of proximal development in Chapter 6).

Drive

In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel Pink discusses research from the last 50 years on intrinsic motivation—motivation that comes from within ourselves. Carrot-and-stick enticements, or extrinsic rewards, not only don't work in the long run but may actually lower performance, stifle creativity, and decrease the desired behavior. We have an inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and build our capacities, to explore, and to learn (Pink, 2009). Mostly people are motivated to do interesting work with supportive colleagues.

In his research, Pink found that people do not respond to monetary rewards and punishments as compared with being given the opportunity for

- autonomy—people want to have control over their work;

- mastery—people want to get better at what they do; and

- purpose—people want to be part of something that is bigger than they are.

Grit

Another popular look at motivation includes research gathered by Angela Duckworth, a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She suggests that grit entails "working strenuously toward challenges, maintaining effort and interest over years despite failure, adversity and plateaus in progress" (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007, p. 1087). Duckworth and her colleagues define grit as "perseverance and passion for long-term goals," (p. 1087). Grit can be a positive indicator of success in the long haul. It adds the component of passion to the trait of persistence. The Intelligence Quotient (IQ) is not always the determining factor in student success, but grit can be, although it is not tied to intelligence. We need to rethink how hard and where we challenge students with unfamiliar and uncomfortable tasks. Many students with a high intelligence may decide to take the safe route and are not particularly successful in life, whereas students with average intelligence and a good level of grit often far surpass their high-ability peers as grit predicts success beyond talent.

Grit is not just having resilience to overcome adversity, bounce back from challenges, or survive at-risk environments. Grit is also staying the course, much like the Tortoise in the famed fable. The Tortoise persists even though his journey is slower and more tedious. The Tortoise wins the race because the Hare (a more talented runner) meanders and becomes distracted along the way. Grit is about being able to commit over time and remain loyal to goals that are set (Duckworth et al., 2007). Developing grit requires multiple rehearsals with content or skills to achieve success and develop mastery. We teachers must tap our creativity to provide the practice that diverse learners need, making sure to offer a variety of multisensory tasks that appeal to students' varied learning preferences. This practice blends the "art of teaching" based on what we know from the research base of impactful strategies, and the "science" of teaching (Hattie, 2009; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001).

We must be careful not to come at grit from a fear-based focus on testing and college selection, especially with young adolescent brains that are more susceptible to negative or critical reactions. Poorly informed teachers and parents may attribute a lack of success to a lack of grit without analyzing the full situation with regard to other issues, such as missing support or resources. Psychologists refer to this sort of misperception as "fundamental attribution error." In addition, perseverance that emphasizes punishments and rewards will undermine long-term grit. Grit is different from passion because grit requires effort and fully engaged commitment to be successful.

The Secret to Success Is Failure

In How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity and the Hidden Power of Character, Paul Tough (2012) makes significant contributions to Duckworth's notion of grit in regard to education. He postulates that in the real world, learning to react to failure is as critical to success as academic achievement. Noncognitive character traits such as resilience, persistence, drive, and delayed gratification are as important as cognitive skills (Farrington et al., 2012). If we don't learn how to deal with frustration and obstacles, we are not likely to choose challenging or risky paths and will perhaps lead a life of mediocrity and predictability. The trait of delaying gratification is necessary to persevere despite encountering obstacles.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EI) is a person's ability to use her or his emotions mindfully. It consists of a balance between emotions and reasoning. Daniel Goleman (1995) believes that EI, like grit, is more important than IQ.

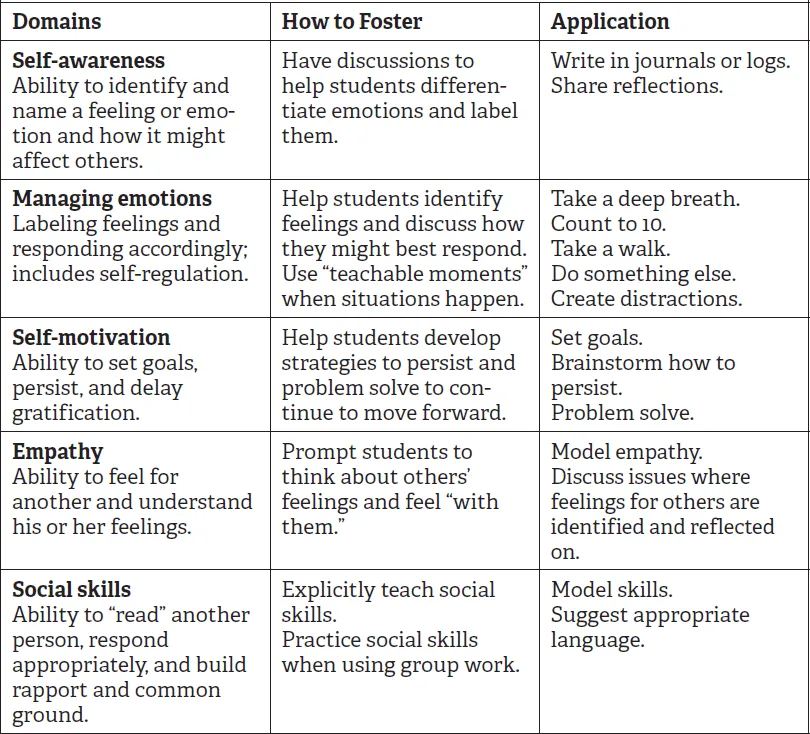

Goleman describes EI as composed of five emotional competencies, or domains: self-awareness, managing emotions, self-motivation, empathy, and social skills. He regards these domains as the keys to success in the 21st century.

- Self-awareness. This domain entails our ability to identify and name our feelings and to articulate our emotions. We can differentiate with precision a feeling and identify (beyond a basic feeling such as sadness) the more complex feelings of anxiety, upset, depression, or disappointment. We are not engulfed with the feelings and can name and then deal with them.

- Managing emotions. Once feelings are labeled, we can begin to think about how to handle them—how to soothe or change the mood or, if anger is the issue, how to resolve conflict.

- Self-motivation. If we can motivate ourselves, we can develop competencies such as setting goals, delaying gratification, and persisting. Being able to self-motivate is actually a state of mind—a certain level of mindfulness. Those who are self-motivated are often more successful in life, unrelated to their socioeconomic position and cognitive intelligence, because they have an inner drive and determination to persist.

- Empathy. Empathy is the ability to feel for someone else or to stand in another's shoes. Being able to read and understand the feelings of another builds tolerance.

- Social skills. People with good social skills have the ability to use interpersonal skills to interact appropriately with others. They are able to read and respond to people in a positive way. They are said to have "social polish." Their teamwork skills are refined, they are collaborative, and they have social influence.

Emotional intelligence derives from the communication between your emotional and rational "brains." Initially, primary senses enter the spinal cord and move through the limbic system (emotional center) to the frontal lobe of your brain before you can think rationally about your experience. In other words, an emotional reaction occurs before our rational mind is activated. Emotional intelligence requires a balance between the rational and emotional centers of the brain (see Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Emotional Intelligence

Plasticity is the term neuroscientists use to describe the brain's ability to grow and change. The change is incremental, but as we consciously practice new skills, permanent habits form. Using strategies to increase emotional intelligence allows the creation of billions of neural connections (dendritic growth) between the rational and emotional areas of the brain. A single cell can grow up to 15,000 connections (dendrites) with nearby neurons. We make new connections as we learn new skills, including emotional intelligence strategies. Practicing will strengthen those neural connections, and over time new behaviors will become habits.

Figure 1.3 lists the five domains of emotional intelligence and suggestions to foster this trait in students, with possible applications that may support the domain.

FIGURE 1.3 How to Foster Emotional Intelligence

Source: Adapted from Bradberry and Greaves (2009). This resource provides concrete, practical ways to increase one’s emotional intelligence.

Belief Through Effort

Fredricks (2014) suggests a view of engagement that considers behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement and their integration.

Behavioral engagement consists of such things as positive actions (e.g., compliance with classroom rules and school norms), nondisruptive behaviors (attendance and orderliness), effort and participation, and school community involvement (sports and clubs). Students who have behavioral engagement "play the school game" and it is easy to observe these students. Engagement here refers mainly to on-task behavior.

Emotional engagement entails students' emotional reactions to school, whether there is a feeling of belonging, and whether they value tasks and school. Emotionally engaged students are vested in school and connected to it. This type of engagement is often overlooked. The more interest, positive attitude, and task satisfaction (without anxiety, stress, and boredom), the greater the engagement.

Cognitive engagement refers to students' investment in tasks and challenges, as well as their perseverance in completing and tackling challenges. They are aware of what they are doing and why, both hands-on and "minds-on" for a specific strategy or task. Cognitive engagement also includes self-regulation, strategic planning, and reflection. It often is described as "deep" rather than "surface" learning.

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) suggests that we are driven by a desire to continually grow and reach fulfillment (Deci & Ryan, 1985). We are centrally concerned with how to move ourselves or others to act. We need to master challenges and experiences to develop our sense of self. Deci and Ryan recognize two basic reward systems, intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic rewards tap into inner potenti...