![]()

Chapter 1

Debugging the School

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

How is it that some schools make progress and others do not? In other words, what do highly effective schools do that makes a difference? The answer is fairly obvious. Effective schools use information that is available to them to continuously improve. Those improvements might be related to the culture of the school, the cleanliness of the facility, or the instructional program. The data—information—focus the efforts of the staff members on areas of strength and need.

The problem is not that some schools have access to information and others do not. Schools are awash in information about most aspects of their operation. Some schools just choose to ignore the information that is available to them. Other schools take a look at the information, perhaps take the time to acknowledge the problem, and then do nothing further about it. And still other schools examine the data, develop an intervention plan, and then fail to implement or monitor the plan. This book examines schools that function differently—schools that make a difference by using information available to them to continuously improve, specifically in the area of instruction. Starting with the assumption that opportunities for improvement always exist, we must purposefully seek out errors, understand their causes and effects, and then fix them for continuous improvement to occur. In the parlance of computer programmers, this process is called debugging. As such, continuous assessment can be used by virtually any educational system to study and then improve the experiences and outcomes of the people who teach and learn there. We are not saying that continuous instructional improvement is easy; we are saying that it is worth the effort.

Why Focus on Instruction?

The primary function of schools is to facilitate learning, which is accomplished through instruction. From years of study, the educational community knows quite a bit about effective instruction: that the climate can enhance or reduce learning (Wright, Horn, & Sanders, 1997), that learning is a reciprocal process that occurs between teacher and student (Brophy, 1982), and that teacher expertise matters (Darling-Hammond, 2000; Shulman, 1987). This last point has been made abundantly clear through a large-scale longitudinal study of the economic repercussions of access to high-quality teaching. Three economists (not educators) drew from two sources of data—federal income tax records and standardized test scores—from 1988 to 2009. These two data sets are readily available, but not commonly linked. The economists' ingenious approach? Investigating the economic impact of a high-value teacher (top 5 percent) on the lifetime earnings of a student. Their analysis revealed that having a high-value teacher for one year correlated with a $50,000 lifetime earnings increase for that student (Chetty, Friedman, & Rockoff, 2011). They further reported that these students were more likely to go to college, and that the girls were less likely to become teenage mothers. By definition, not every teacher can be in the top 5 percent; it is mathematically impossible. But the most encouraging news is that replacing a low-value teacher (bottom 5 percent) with an average one equated to overall lifetime earnings that approached $1.4 million dollars per class of 27 students.

The economists' study speaks well to the continuous investment that should be made on the quality of instruction. Increasing teacher expertise positively affects the quality of life for our students long after they have left our classrooms. Replacing a low-value teacher doesn't need to be swapping out one individual for another; "replacing" could mean effectively supporting each teacher's professional growth. What if the instructional skills of every teacher were increased? Consider the effect this change would have on students. Do you know any teachers who aren't eager to become more expert at what they do? If so, they are in the minority of your collegial group. As educators, we all desire to be better at our job today than we were a year ago. We want to hone our teaching skills. But after the first few years of practice, during which we work out the obvious kinks of classroom management, lesson planning, and organization, where do we turn?

Our answer is that a climate exists within a successful school where data analysis, both quantitative and qualitative, informs instructional expertise. In too many schools and districts, data analysis is viewed as something separate from the daily life of the classroom. In too many instances, data analysis is reserved for a professional development session or scheduled for professional learning community discussions. These events are finite, with a start and stop time, and are only fitfully carried into the classroom. The challenge, as we see it, is to view data—not intuition, not anecdotal reports—as the tools we use to get better at teaching students. To get better at teaching requires us to relentlessly focus our attention, with laser-like precision, on instructional practice and improvement.

Focusing on Instructional Improvement

The first three phases of the instructional improvement model we propose have a lot in common with other systems that have been developed (e.g., Bambrick-Santoyo, 2010). More specifically, any instructional improvement system should begin by surveying the information available within a school—both hard and soft data—which is the focus of Chapters 2 and 3. Collecting hard and soft data require that school teams and their leaders develop assessment literacy, meaning that they come to understand what the assessments do and do not measure as well as the validity and reliability of the collected information.

In addition, a systematic approach to instructional improvement requires that data are analyzed to identify patterns of strength and need. The vast amounts of data that are available can overwhelm school teams to the point that they become paralyzed in the analysis phase and are unable to use the analysis to move to action. We have found it important in this phase to take time to celebrate successes and achievements. Although instructional improvement is about continuous progress, taking time to recognize areas of growth builds the capacity of the teams while reinforcing the notion that their efforts are rewarded.

The third part of a traditional approach to instructional improvement focuses on using the insights that were highlighted through analysis to develop goals and objectives that can drive the school improvement process forward. In high-performing schools, teachers and leaders engage as a community in all three phases of this process, from data collection to analysis and goal development. Developing specific and shared goals helps focus the efforts of a school and guides decisions about professional development and spending priorities, ensuring that there is significant community stakeholder involvement and investment in the outcomes.

Unfortunately, at this point in the process, many instructional improvement efforts end. In some situations, school teams meet at the beginning of the year, review their data from the previous year, and develop goals based on observed patterns. Then the school year starts and the well-meaning adults within these systems become busy as they do their best to meet the goals, but are unable to continue to assess the success of the implementation in all areas that affect students, faculty, staff, administration, and curriculum. The situation could be worse. Imagine a school where the principal independently analyzes data and then announces the goals for the year to the faculty and staff. Or worse yet, the leadership team receives information from the state assessments and files it away in a drawer, meaning to look at it later.

Despite good intentions, it's no wonder that some schools fail to improve. Instructional improvement is not the sole responsibility of the principal or even the leadership team. It is a shared responsibility of all the school's stakeholders, including students, parents, community members, classified staff, faculty, and administrators. It's also not about the plan itself. Simply writing goals and objectives for school improvement and sending the list to the district office or state department of education will not likely change the experience students have in school.

Following a Process

Developing an improvement plan is vital and will be addressed in more detail in the coming chapters. Let's temporarily put that to the side so we can highlight what happens after the plan is developed. Most conventional plans acknowledge that implementation and monitoring are important, yet offer few details on how that might be accomplished. Some teams assume that, once crafted, the details of the plan will fall into place. But then the inevitable occurs—competing priorities overwhelm the best of intentions and the plan is derailed. We contend that implementation and monitoring are all about building, maintaining, and extending the competence and confidence of everyone involved. And to do so, administrators need to see themselves as learners and to understand what it means to be a learner.

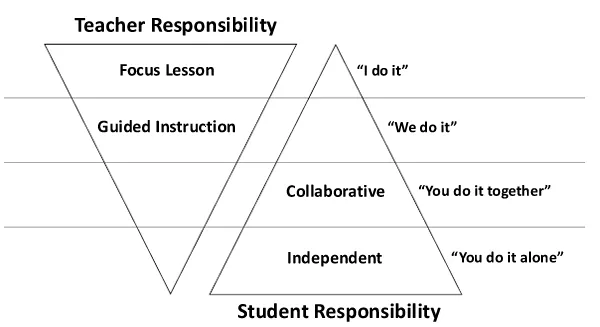

When it comes to developing our own students' competence and confidence, we turn to a gradual release of responsibility instructional framework (Fisher & Frey, 2008a). The framework is informed by the reading comprehension work of Pearson and Gallagher (1983) who provided a means for describing the shifting levels of cognitive responsibility between teacher and student as the learner gains knowledge and skills. Our own work has further expanded this view by including other vital aspects of instruction, including setting purpose and fostering collaboration among peers. Concepts and skills are introduced to students through focus lessons that include statements of purpose as well as modeling, demonstrating, and thinking aloud by the teacher. The cognitive responsibility shifts a bit toward students during guided instruction, when they get an opportunity to apply the skill or concept under the watchful gaze of the teacher, who is available to help when understanding breaks down. Students use these skills and concepts in collaborative learning arrangements, where vital opportunities to make mistakes are paramount. As competence and confidence grow, the student is able to assume an increasing level of cognitive responsibility to learn independently and continue building knowledge. Figure 1.1 contains a diagram showing the shifting cognitive and metacognitive responsibility at each phase of learning.

FIGURE 1.1. GRADUAL RELEASE OF RESPONSIBILITY INSTRUCTIONAL FRAMEWORK

Source: Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2008). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility (p. 4). Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Used with permission.

The same principles for learning apply to adults. Our collective competence and confidence require the same kinds of scaffolds and supports. As with a classroom instructional framework, these concepts and skills rarely roll out neatly in a single lesson but are built over many lessons that occur over days, weeks, and even years. One notable difference in this instructional frame when we are teaching and learning with K–12 students versus when we apply it to support work with a faculty team is that the roles of "teacher" and "student" are not so clear cut. Within the context of instructional improvement, the "teacher" may be an instructional leader, the reading coach, or the 5th grade team, and the "student" may be the instructional leader, the reading coach, or the 5th grade team. Depending on what is being taught and learned, the roles should shift fluidly. We'll look at each phase of the gradual release of responsibility through the lens of instructional improvement.

The focus lesson

Purpose is established for the group, driven by the data or the need for the data, and it is essential for stakeholders to know exactly what is being done and why. For example, a school might analyze data and determine that mathematics achievement among students with special needs has stalled. An agreed purpose might be that the mathematics teachers need to learn more about the principles and application of universal design for learning (UDL). To accomplish this, the teachers and the principal might schedule several professional development sessions with the district math coordinator to build their skills. In these sessions, the teachers will have an opportunity to witness how UDL principles are used within the discipline. The math coordinator uses videos and lesson examples to model and demonstrate these applications and to think aloud about how she determines when, where, and for whom they are best suited.

Guided instruction

What does or does not occur after focus sessions has a direct effect on whether there is implementation. Joyce and Showers (2002) demonstrated that for professional knowledge to transfer to classroom practice, a system of follow-up support and instruction must exist. We believe that, in many cases, the transfer is expected to happen too quickly and teachers are expected to collaborate with one another too soon. Complex instructional practices like UDL, for example, are rarely immediately put into play. Yet without action, teacher collaboration and discussion of practice cannot occur. In many cases, what needs to happen after the initial focus lesson is some guided instruction. Guided instruction occurs when small groups of learners try out newly learned skills with an expert analyzing their learning using questions, prompts, and cues (Fisher & Frey, 2010b). In the instructional improvement process, guided instruction might include work sessions with a team of teachers.

For example, the primary and intermediate grade teachers who participated in the initial professional development sessions with the district math coordinator decided to break into smaller groups to work with the special educators assigned to their grade bands. K–2 general education teachers worked together to analyze their math curricula to identify possible areas to improve using UDL principles, while the special educators for each grade level guided their understanding. During the work session, one of the special educators recognized that several math teachers possessed the misconception that one UDL accommodation alone would meet the needs of all students with special needs. She used questions, prompts, and cues to draw their attention to what they knew about individual students. The general educators soon realized that because of their students' diverse needs, more than one accommodation would be necessary to realize the UDL principle of making information perceptible.

Collaborative learning

In this phase, learners work together to refine their collective understanding of a concept or skill. Collaboration is essential to learning because it is the phase where errors can and should occur on a regular basis. Errors are critical to the learning process, as they illuminate what we know and still don't fully understand. This phase also primes learners for subsequent instruction, as they become more attuned to locating information to fix errors. In the case of the primary math team, they tried out the materials they had created using UDL principles in their own classrooms and then met in their professional learning community to report on their progress and areas of difficulty. During the course of their discussion, teachers brought examples of student work to analyze together. Teachers found that most of the targeted students had performed better than expected using the materials, but they also discovered that in two cases the students performed worse. The team members suspected that although they had designed and implemented the UDL accommodations adequately, they did not agree on the underlying mathematical concept they were teaching and consequently testing. Confounded by these findings, the teachers invited the school's math coach to do some follow-up guided instruction with them on the finer points of using mathematical models to explain concepts.

Independent learning

Learning is always iterative, in that it always moves forward and serves as a gateway to new inquiry. Our march toward learner independence is so that the learners we are charged with teaching can resolve problems outside the classroom. Similarly, in a continuous instructional improvement process, educators are increasingly able and willing to apply concepts and skills to new situations over time. But to do so, they need to have a sense of competence and confidence, also known as self-efficacy. For instance, 1st grade teacher Kim Larson discovered that she had a talent for and interest in using UDL principles and began to use these as a lens for looking at her curriculum. In time she attended several webinars and conference sessions on universal design for learning. After reading a book on UDL, Teaching Every Child in the Digital Age (Rose, Meyer, Strangman, & Rappolt, 2002), Ms. Larson used an online tool to analyze curriculum for barriers as part of the professional development for teachers new to their school (see http://www.cast.org/teachingeverystudent/tools/curriculumbarriers.cfm). By combining her experiences with learning about UDL and applying these principles in her own classroom, Ms. Larson has evolved from being strictly a learner to facilitating the learning of others. In the next section, we will look more closely at how a middle school has woven the processes of gathering and analyzing data with those that focus on professional development cycles to foster continuous instructional improvement.

Instructional Improvement in Action

The faculty and staff of Mountain View Middle School met in late August to review student performance data. This school educates more than 1,000 students in grades 6–8, with 62 percent of the students qualifying for free lunch and 35 percent classified as English language learners. Within three years, the students at Mountain View made considerable progress. The achievement gap was closing, and students were performing at higher levels than ever before. The school attributes the gains to a systematic instructional improvement effort that starts with regular reviews of data and the development of goals and objectives that drive its curriculum and professional development work.

At the start of the school's data review session, the facilitator invites faculty and staff to a campfire—a metaphor for the interactions they will have with one another. The room is arranged in a circle of chairs, with tables and materials pushed to the outer perimeter. Faculty and staff are invited to share their celebrations, news, and greetings from the summer. The facilitator of this meeting is the mathematics department chair, Marc Rose. In other meetings, different faculty and staff members have served as the facilitator. Mr. Rose reminds participants that it's impossible to drive by looking only in the rearview mirror, and that the purpose of data is best served when it is used to determine where to go next. Following a 20-minute campfire conversation, Mr. Rose transitions the conversation to the purpose of their work at that time: understanding and analyzing the data, formulating the right questions, and figuring out the next steps. Two questions are posted on chart paper on the wall:

- What do we know from the previous school year's data?

- How does this information compare to prior years?

Participants are invited to walk around the room and discuss the data charts. These visua...