![]()

PART I

Developing and Leading a Literacy Culture

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenario: Barnum Elementary School

Four years ago, teachers at Barnum Elementary School would have told you that their instructional practices were above average—or at least average. However, students' performance on standards-based and achievement assessments during that time told a different story, especially in the area of reading.

With the data challenging our assumptions, we couldn't hide from the reality that we needed to change our teaching practices. We wanted our students to grow and achieve. We did not want the stigma of having underperforming classrooms to cause divisiveness or finger-pointing within our community. By discussing our student data, the leadership team and the teachers decided to come together, create common practices throughout the school, and support both team and individual growth.

We decided to shift the focus from student test scores to our teaching practices. Taking the emphasis off of test scores gave our teachers room to breathe and freed us from the emotional baggage that low test scores can bring, allowing us to grab on to practices that transformed our school's literacy culture.

At first, we purchased resources and tried a variety of "one and done" workshops to broaden our teaching practices. Once we realized that this piecemeal approach was not getting us where we wanted to be, we incorporated the Literacy Classroom Visit Model. The LCV Model provided a way for us to examine our school's literacy culture and the effectiveness of our current instruction. We gained a common language and common expectations. This schoolwide effort didn't happen in a vacuum but was accompanied by plenty of debate, discussion, and professional development.

Over time, we used the LCV Model to gather schoolwide, grade-level, and, eventually, individual teaching data. We moved from having individual and common grade-level practices to setting consistent schoolwide expectations. Our focus on developing a schoolwide culture of literacy helped us provide meaningful professional development tailored to the specific needs of our building, teacher teams, and individual educators. The results speak for themselves: we went from being a Continuous Improvement school where teachers were doing many good things to becoming a Reward School where all teachers are guided by research-supported best practices within our established expectations for literacy.

The LCV Model was instrumental in providing the clarity and focus that we needed across our K–6 instruction. Our test scores and LCV data now prove that we are providing above-average instruction. Just ask any teacher in the building!

Tom Cawcutt, Principal

Barnum Elementary School

Barnum, Minnesota

![]()

Chapter 1

Making the Case for the Literacy Classroom Visit Model

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Schools that have successful literacy programs show evidence of strong principal leadership, with focused attention on setting a literacy agenda, supporting teachers, accessing resources, and building a capacity for further growth.

—David Booth and Jennifer Rowsell, The Literacy Principal

School leaders assume the heavy responsibility of ensuring continuous learning for both teachers and students. Although many educators who enter the administrative track tend to drift away from the areas of teaching and learning, principals need enough content knowledge to be able to assess the instruction they see (Fink & Resnick, 2001).

The role of the principal as instructional leader is becoming increasingly important in light of the current focus on teacher effectiveness and a growing consensus in the field on what effective teachers do to enhance student learning (MET Project, 2013). Since researchers have begun to quantify the average effects of specific instructional strategies (Marzano et al., 2004), educators should, in theory, be able to close the gap between what they know works and what they are doing in their classrooms.

Yet despite increased scrutiny of literacy instruction, little has been done to examine the specific knowledge that principals need regarding literacy teaching and learning, or how districts can build literacy leadership capacity. As Reeves (2008) noted, "If school leaders really believe that literacy is a priority, then they have a personal responsibility to understand literacy instruction, define it for their colleagues, and observe it daily" (p. 91).

Leaders' Role and the Need for Data

So, how can leaders go about fulfilling this responsibility? Along with the job of recruiting, hiring, and sustaining quality staff who enhance students' overall literacy learning, a literacy leader must gain an understanding of literacy teaching practices and be able to help classroom teachers ensure that all students learn to read, write, and think critically about different kinds of texts. Education leaders who are not proficient in their knowledge of literacy instruction have a difficult time determining the key qualifications that excellent teachers possess (Stein & Nelson, 2003).

Thus, leaders need a system to collect and analyze timely and useful information about (1) the current instructional practices in their schools and (2) how students engage and collaborate in the process of learning. These data must be collected consistently, with a clear purpose and without the intent of using them to evaluate individuals' teaching performance. Data collection should focus on how the instructional learning environment and classroom practices foster student learning, and the data should be used to celebrate areas of success and illuminate areas of need. Leaders can then address the areas of need by providing teachers with targeted professional learning opportunities and other resources. The method of data collection should also provide a way to determine how well these resources and learning experiences are effecting the intended changes in teaching and learning.

The Power of Classroom Visits

Research (Protheroe, 2009) supports the value of regular classroom visits as integral to the ongoing work of education leaders. These visits may take the form of instructional rounds, walkthroughs, observations, or any series of scheduled visits that can either capture broad impressions of overall instruction or home in on key areas. Typically, these visits are done informally for the purpose of data collection and professional growth. However, in some instances, districts and school administrators use them as part of their formal observations in the evaluation process.

Conducting informal observations enables school administrators to evaluate job-embedded professional development initiatives, collect evidence related to curricular programs, and identify trends in instructional practices (Stout, Kachur, & Edwards, 2009). Ideally, the process also provides teachers with the feedback they need to evaluate their own effectiveness in applying their professional learning (Hopkins, 2008).

____________________

Frequent, brief … walkthroughs can foster a school culture of collaborative learning and dialogue. (Ginsberg & Murphy, 2002, p. 34)

____________________

Walkthroughs and instructional rounds both have a defined purpose and can provide rich and useful data for education leaders. Establishing time and a process for classroom visits, as these practices do, can help leaders establish themselves as instructional leaders and mentors; familiarize themselves with the climate, curriculum, and practices in the building; and develop partnerships in discussing common practices and needs (Ginsberg & Murphy, 2002). The classroom walkthrough process can also create a framework for designing and evaluating schoolwide professional development (Cervone & Martinez-Miller, 2007) and be used to increase student achievement (Skretta, 2008). Although walkthrough models may vary in design and implementation, their goal remains the same: to enhance student learning and achievement by improving instruction (Scott, 2012). Instructional rounds are another method of gathering data, involving teams that work collaboratively to make sense of their observations and draw logical conclusions (City, Elmore, Fiarman, & Teitel, 2009).

Concerns About Walkthrough Protocols

In practice, classroom observations can fall short of their intended purpose unless considerable care has been given to the walkthrough form and the feedback process. Too often, the walkthrough form consists of broad checklists of generic practices that do not identify a clear purpose or articulate specific instructional "look-fors" and thus do not provide leaders with the information they need to give appropriate or accurate feedback (Pitler & Goodwin, 2008). With respect to literacy in particular, without a clear understanding of what effective literacy instruction looks like, this method accomplishes little (Hoewing, 2011).

Sometimes walkthroughs are used for individual teacher evaluation, which goes against the intent of the original practice. In such cases, feedback is given to individuals after only a few short visits to their classrooms, diminishing trust in the process as well as the leader. As many scholars (DuFour & Marzano, 2009; Liu & Mulfinger, 2011) have asserted, the current teacher evaluation system in many schools across the United States—which incorporates walkthrough practices—is flawed because feedback is infrequent and broad or focused on areas other than quality instruction.

If leaders do not clearly communicate the purpose of their walkthroughs and look for specific, research-supported instructional practices that have been discussed with teachers, the observation and the feedback they provide may be worthless or, worse, damaging to educators and students alike (Pitler & Goodwin, 2008). The process can also create significant anxiety and resistance among teachers. In order to be an effective tool for instructional improvement, the culminating data must be used to identify professional learning and resource needs that are known factors in teacher effectiveness and student achievement (Ginsberg, 2001).

The LCV Model: A Better Way

Literacy Classroom Visits incorporate the best aspects of walkthroughs: they are brief, frequent, informal, and focused visits to classrooms by observers whose purpose is to gather data about teaching practices and engage in collaborative follow-up. Like instructional rounds, Literacy Classroom Visits can be conducted in teams and focus on student learning and collaborative discussion around descriptive, nonjudgmental data. However, they are unique in that they concentrate specifically on research-supported practices that have a direct effect on literacy achievement.

The Literacy Classroom Visit Model is also distinctive in terms of how data are collected and analyzed to direct the focus on specific data patterns. These patterns highlight instruction and learning of the community rather than the practices of individuals. Over time, they reveal evidence of a developing culture of literacy as well as effective practices that integrate balanced literacy instruction and the gradual release of responsibility (approaches that we delve into in subsequent chapters).

No matter how wonderful they are, reading programs, resources, and research-based approaches are productive only when used by effective teachers using proven practices for excellent instruction (Allington, 2002). Finding the sweet spot among what research says about effective instruction, what teachers know and are doing in the classroom, and how these elements intersect with student development can be challenging. The LCV Model provides a solid vehicle to find this crucial intersection, combining research about best practices in literacy instruction and classroom delivery methods with how students engage and learn to read and write. The data gathered during these visits provide the information that teachers need to be most effective.

What Are We Looking For?

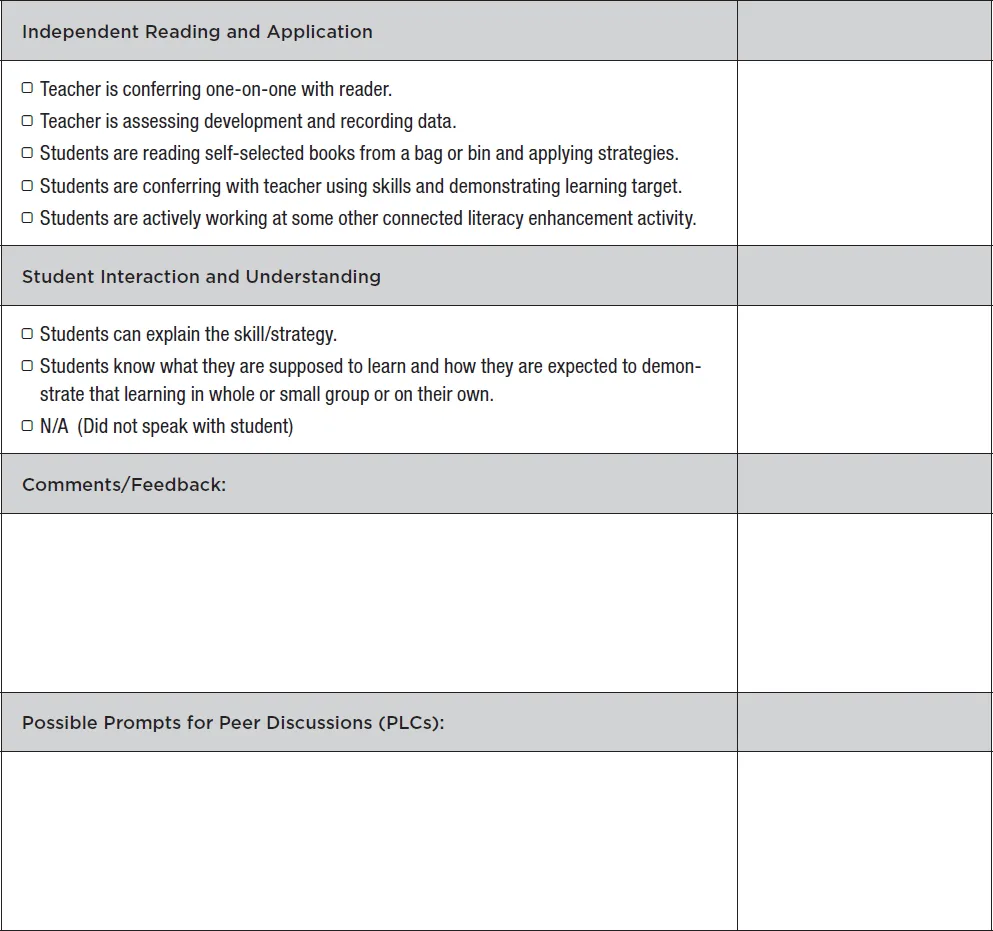

Literacy Classroom Visits are seated in research-based practices that are essential to helping students become critical thinkers, effective readers, and meaning makers. The "look-fors" listed on the LCV instrument (see

Figure 1.1, also available

online) are a carefully distilled and field-tested compendium of research-supported instructional practices specific to literacy. In addition, the LCV instrument integrates general instructional best practices, such as the gradual release of responsibility (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983), differentiated instruction (Tomlinson & Allan, 2000), and purposeful student engagement. The resulting formula creates a strong foundation of instructional practices that promote student growth and achievement.

Video 1.1 provides an overview of the full process.

Figure 1.1 | Literacy Classroom Visit Instrument

Source: © 2014 by Bonnie D. Houck, EdD. Used with permission.

Collecting Literacy Classroom Visit data over time can

- Establish a body of evidence about a school's or district's overall literacy culture and instruction.

- Identify instructional patterns within teacher teams...