Social-Emotional Learning and the Brain

Strategies to Help Your Students Thrive

- 219 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

ASCD Bestseller! Today's teachers face a daunting challenge: how to ensure a positive school experience for their students, many of whom carry the burden of adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, poverty, divorce, abandonment, and numerous other serious social issues. Spurred by her personal experience and extensive exploration of brain-based learning, author Marilee Sprenger explains how brain science—what we know about how the brain works—can be applied to social-emotional learning. Specifically, she addresses how to- Build strong, caring relationships with students to give them a sense of belonging.

- Teach and model empathy, so students feel understood and can better understand others.

- Awaken students' self-awareness, including the ability to name their own emotions, have accurate self-perceptions, and display self-confidence and self-efficacy.

- Help students manage their behavior through impulse control, stress management, and other positive skills.

- Improve students' social awareness and interaction with others.

- Teach students how to handle relationships, including with people whose backgrounds differ from their own.

- Guide students in making responsible decisions.

Offering clear, easy-to-understand explanations of brain activity and dozens of specific strategies for all grade levels, Social-Emotional Learning and the Brain is an essential guide to creating supportive classroom environments and improving outcomes for all our students.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Building Teacher-Student Relationships

The brain is most interested in survival and has a deep need for relating to others.—John Medina

When it comes to the subject of history, there isn't a finer teacher than Sarah. She loves her content and can often mesmerize her students with stories, monologues, and rare tidbits of information about a country's war heroes and relationships, both personal and professional. When the school survey was given to 6th through 12th grade students, however, Sarah did not fare well.She was crushed when she reviewed the answers her students gave in several areas. Although 88 percent of her students agreed that Sarah explained things in a different way if students didn't understand, only 15 percent said that she noticed when they were having difficulty, and only 5 percent said that she helped them when they were upset.At first, Sarah was angry. She thought, "With all the time I spend preparing the best lessons for them, making sure that I help them see and hear history, how can they say I don't notice their content and personal issues? What's wrong with them?"By the time Mr. Mercer called her in for a meeting to discuss the results, Sarah had begun to calm down and was trying to figure out how the students had come to their conclusions. She sat down across from her principal and mentor. He smiled and began by saying, "Sarah, you know you are a great teacher and you reach most of your students. Your teaching style is above reproach. My observations in your classroom have shown me how you can dazzle reluctant learners, and whether I'm observing your 8th graders absorbing the nuances of the Civil War or your 10th graders tackling the reasons leading up to the war in Vietnam, your kids view you as a knowledgeable historian. You can make them feel connected to Holocaust victims and survivors, but you don't seem to make them feel connected to you! It wasn't until I studied the surveys that I realized this."I apologize for not looking closely enough to realize that you have a relationship with your class, but you don't really relate to your individual students. That is, you don't have a personal relationship with them. Your dynamic presentation of material draws them to the content, but you must establish a way to draw them to you. They need to trust you as a person. Many of them need to feel noticed as individuals. Seventy-four percent say that you give them specific suggestions for improving their work, and out of the 150 students you teach, that says a lot. But only 25 percent say that you support them both inside and outside the classroom. Let's talk about what you can do to increase this. You see, the students who are upset about this are the ones who can't get your full attention, the kids who need to know someone cares about them, not just their content or their grades."It's not always easy to build relationships with pre-adolescents and adolescents. You and the other adults in their lives are their last best chance to get beyond some of the trauma and stress they experience—many on a daily basis."At this, Sarah sat back in her chair and sighed. "Mr. Mercer, I've never been good with relationships. Even though I can conjure up unusual and interesting lessons, I don't relate to people well. I think I need to take a course!"

Maslow Before Bloom

Relationships in the Brain

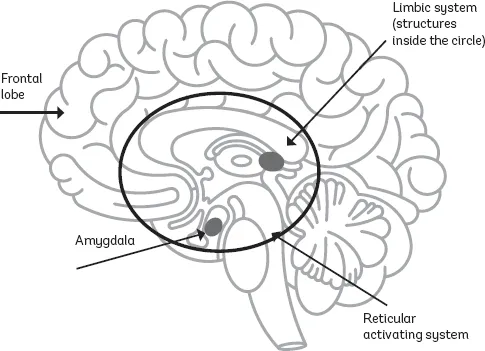

Figure 1.1. Relationships in the Brain

Strategies for Building Teacher-Student Relationships

Display Vulnerability

Greet Students at the Door

- Say the student's name.

- Make eye contact.

- Use a friendly nonverbal greeting, such as a handshake, high five, or thumbs-up.

- Give a few words of encouragement.

- Ask students how their day is going.

They were 5th graders. It was a tough school, a tough crowd. It was hard for me to believe that 11-year-olds could be scary—that is, until I stood before them. I was acting assistant principal when one of our 5th grade teachers divorced her husband, broke her contract, and moved away with her two kids. She had been struggling for months with her marriage and had used up all her sick days for mental health reasons and to see her attorney.The students at this school came from backgrounds of generational poverty or broken homes or had a parent in prison. They had trusted this teacher, and slowly, over time, she had let them down, just as their parents had let them down. When she left, the students trusted no one and found yet again that they were alone in the world. They were angry. And we know that anger is the bodyguard of fear. They were afraid to trust. After several subs came and went, we decided that I would take over this cla...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- ASCD Member Book / Also by the Author

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Building Teacher-Student Relationships

- 2. Empathy

- 3. Self-Awareness

- 4. Self-Management

- 5. Social Awareness

- 6. Relationship Skills

- 7. Responsible Decision Making

- 8. People, Not Programs: The Positive Impact of SEL

- Glossary

- References

- Study Guide

- Related ASCD Resources

- About the Author

- Copyright