![]()

Part I

The Basics of Grading for Learning

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

![]()

Chapter 1

All Students Can Learn

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"Will this count for my grade?" an anxious student wants to know. Most students start school wanting to learn, but common educational practices, especially conventional grading, conspire to change students' attitudes as they go through school. By their later elementary school years, most students talk about grades more than they talk about learning, and this preoccupation continues through high school and beyond. As students progress through school, their dissatisfaction with and cynicism about grades increase and their belief in the fairness of grades declines (Evans & Engelberg, 1988), starting perhaps as early as 3rd grade (John Antonetti, personal communication). How did it come to this? What have we done?

The Foundation

The premise of this book is the implicit promise or commitment teachers make to their students: In my class, in this school, all students can and will learn. Students won't all learn the same things at the same level of proficiency or in the same amount of time, but if students are in school, they are there to learn something. It doesn't take much of a leap to get to the implied questions: So, did they learn? What did they learn, and how well?

Grades are imperfect, shorthand answers to these questions. Assignment grades are summaries of student performance on specific pieces of work. Report card grades are summaries of student performance over sets of work. These sets of work are usually intended to reflect learning goals derived from state or provincial standards. This book will show how to produce grades— both for single assignments and for report cards—that effectively communicate students' achievement of these learning goals.

Of course, grades are not the only answers to these questions. Conferences with students and parents, narrative reports, and other communication methods can supplement grades. Given the number of students in the education system, however, some sort of efficient summary grade has seemed necessary, at least since the advent of the common school (S.G.B., 1840/1992). In almost every school system today, assigning grades is part of a teacher's job. So if you have to do it, you might as well do it well!

Two big ideas follow from this foundation. These ideas should undergird your grading decisions. School and district grading policies should be consistent with them. They are the principles on which all the recommendations in this book are based.

- Grades should reflect student achievement of intended learning outcomes.

- Grading policies should support and motivate student effort and learning.

Principle 1 addresses the implicit question "How well did students learn (on this assignment or during this reporting period)?" Principle 2 addresses the larger question of how to create the kind of atmosphere that supports learning. Grading policies that are intended to elicit student compliance are not conducive to the active pursuit of learning.

The current climate of standards-based reform forces these issues for us. Perhaps you, too, feel the pressure that other educators have reported from the large-scale student proficiency testing that has been one of the defining features of this reform (Au, 2007). On the face of it, it seems like the pressure of external accountability assessment would also ramp up the pressure for traditional scoring and grading practices in the classroom. Paradoxically, though, we can actually use the standards movement to advantage. Standards describe the objects of students' achievement—what they are to learn—more clearly than conventional grading categories (mathematics, English, music, and so on). This makes room for standards-based grading and other grading reforms that focus on learning and achievement. What matters is not whether the grading practices are standards based or conventional, but whether they support learning.

How Not to Use Grades

This is a true story about what happens when grades are not about learning. I was fresh out of college and had not yet secured my first teaching position. So, like many of you, I did substitute teaching. Within my first month of subbing, I was assigned to cover four days for a high school social studies teacher. Because he knew he was going to be out, he had planned in advance, and we had a brief meeting the week before he left.

One of his classes was composed of 10 young men who attended vocational-technical school in the morning and came to the high school in the afternoon for their two required academic classes, English and social studies. According to this teacher, they "didn't want to be there," and he was afraid they would pose a discipline problem while he was gone. Therefore, he had given them a group presentation assignment, and my "lesson plan" was to listen to the groups' presentations, one each day, and grade them. The grades I gave would "stick," he said. By that he meant he would really use them in his report card grades. He hoped that this would motivate the students to behave themselves.

I had just completed an elementary teacher-preparation program and had a brand-new K–8 teaching certificate. I had almost no experience with managing high school students. And what was I given as my only instruction? Grade!

If you think this was a disaster waiting to happen, you're right. When I arrived on Monday, I found that three groups had done absolutely nothing and one student in the fourth group had prepared a few note cards to read to the class. The teacher had asked me to turn in grades to him, so I did. I gave Fs to the groups that did nothing and a B to the group that did something, even though it was pretty dismal. It was clear that the students really didn't care one way or the other.

But the feared discipline problems didn't materialize. The students and I mostly just talked. Back then, I felt I had probably wasted their time, that I should somehow have been able to teach them some social studies. I felt badly that I didn't have enough content knowledge to at least tell them something about their topics. Older and wiser now, I realize that in that context these students weren't really going to learn much anyway.

Why not? There were a lot of reasons, as you can probably tell, but the judgmental use of grades was a big contributor. First, grading in that class was about discipline and control. It was the teacher's "big stick." And in this case, it was to be wielded on 10 students who had a long history of being unsuccessful in their academic classes. Not only was this grading plan not about learning, but it sent the message to these students that their teacher didn't trust them (and he didn't). Second, I had been instructed to grade the presentations, but there were no criteria for them, no expectations except that they would fill a 50-minute period and be on certain topics. So the assignment dehumanized the students and disrespected the content at the same time. And group grades are a whole other issue in themselves (Brookhart, 2013b). See Chapter 4 for more about that.

Every time I think of this story, it makes me sad. But I am no longer powerless to do anything about it, as I was then. The grading principles and practices I share in this book are, basically, the opposite of everything in this story. They are designed to help readers be the antithesis of the teacher in this story. Ultimately, they are designed to make school learning better for those ten young men and other students like them.

Common Terminology

Before getting into specifics, it will be helpful to establish definitions for some common terms that will appear throughout this book.

Grade (or mark) is commonly used to mean both the mark on an individual assignment and the symbol (letter or number) or sometimes level (such as "proficient") on a report card (Taylor & Nolen, 2005). O'Connor (2009) uses grade to mean only the mark on a report card, and not the one on individual assignments. However, the dual usage is so common that perhaps the best way to handle it is to accept it and live with it. That is the approach I will take in this book. I will endeavor to be very clear about whether I am talking about individual assignment grades or report card grades.

Grades for individual assignments should reflect the achievement demonstrated in the work. Grades for report cards should reflect the achievement demonstrated in the body of work for that report period. I'll have a lot more to say about that throughout the book, but for now, just consider achievement part of the definition of grade.

Scores are numbers or ordered categories. Some individual assignments, most notably tests, receive scores that result from a scoring procedure. The scoring procedure should be defined. For example, on a test made up of multiple-choice, true/false, or matching items, a typical scoring procedure is to give one point for each correct answer. Tests that have multipoint problems or essay questions require clear scoring schemes that define how to allocate the points.

Validity means the degree to which grades or scores actually mean what you intend them to mean. In the case of grading, if you intend a report card grade to indicate achievement of a standard, the grade should do that—and not, for example, represent attendance, or how appealing a student's personality is, or something extraneous like that. In the case of a classroom unit test score, if you intend the test score to indicate the achievement of a science unit's learning goals, the score should do that—and not, for example, represent how beautiful the student's handwriting is, or how well the student could read very complicated passages in some of the questions.

Reliability is the level of confidence you have in the consistency or accuracy of a measure. So, for example, in the case of that test score, how close is the percentage correct to the real level of achievement "inside the kid's head," and how much is it influenced by the form of the questions, time of day, inaccuracies in the teacher's use of scoring procedures, and so on? There will always be some inconsistencies (errors) in measurement, but you want to keep them as small as possible.

Grading is only one kind of student assessment or evaluation. Both of these terms, assessment and evaluation, are broader in scope than grading. Evaluation means judgment or appraisal of the value or worth of something. All evaluative judgments, not just grades, should be based on high-quality evidence that is relevant to the particular kind of judgment you are making. Assessment is a general term that means any process for obtaining information.

Classes, schools, programs, textbooks, and materials are also commonly evaluated. In this book, we will follow the convention that if we are talking about appraisals of students, we will use the term assessment. If we are talking about appraisals of classes, schools, programs, textbooks, and materials, we will use the term evaluation.

Formative assessment means that students and teachers gather and use information about student progress toward the achievement of learning goals as the learning is taking place. Information from formative assessments helps both students and teachers with decisions and actions that improve learning. Summative assessment is assessment that is conducted after the learning has taken place to certify what has been learned. Grading is one form of summative assessment. Unlike formative assessment, in which students must participate, summative assessment is usually the teacher's responsibility.

Student Assessment

Assessment information that is used for grading is only a subset of all the possible assessment information that is available for a student. Assessment information may be about student achievement, but it may also be about students' attitudes, effort, interests, preferences, attendance, behavior, and so on. All of this information is relevant for knowing your students, providing appropriate instruction, taking appropriate action with regard to student behavior, coaching students in their work, talking with them, and inspiring them. So when in this book we say that grades should be based on achievement information only, that does not imply that you should ignore the rest of the information you have about students.

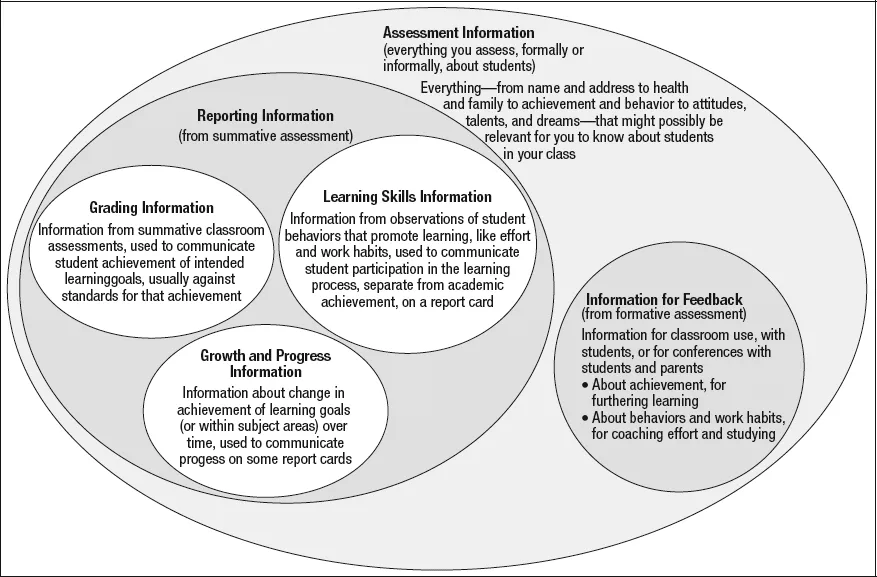

Figure 1.1 presents a diagram of the relationships among all the different kinds of information a teacher gathers about students. Discussions of grading often refer to three of these categories: (1) assessment information (everything a teacher assesses about a student), (2) reporting information (only those measures and observations the teacher reports), and (3) grading information (only those measures and observations the teacher reports in a grade representing student achievement) (Frisbie & Waltman, 1992; O'Connor, 2009). Figure 1.1 completes the picture by adding the classroom-only information that the teacher uses formatively and does not report.

Figure 1.1. Relationships Among Assessment, Grading, and Reporting Information

External Pressures on Grading Policies

Changing grading policies and practices is not simply a matter of deciding to do something different. Grading happens in a context. This context is somewhat different in each community but often includes pressures from parents and community members and from higher education. These pressures tend to favor conventional, competitive grading practices that rank students. Changing grading policies and practices will require addressing these pressures.

Parent and Community Pressures. Parents and community members have definite expectations for grading policies and practices. However, some of these expectations may not be helpful and may present an opportunity for parent education. For example, even parents of young children seem to want schools to use letter grades and to provide information that compares their child to other students (Huntsinger & Jose, 2009). Yet normative grading—comparing students to one another—is harmful educationally (Ames & Archer, 1988; Dweck, 2000). Moreover, the information that Hannah does something better than Johnny and worse than Yolanda reveals nothing about what Hannah actually knows and can do.

In schools with traditional letter grading, parents sometimes misconstrue the meaning of the letters. The "average" letter grade that most teachers give is a B. However, most parents think the "average" grade is a C (Waltman & Frisbie, 1994). So parents whose children bring home Cs may think their student is average when, in fact, the student's grades are among the lowest in the class. Parents' ideas about grading can vary among different communities. In one study, Chinese American and European American parents of students in grades K–4 had different expectations. The Chinese American parents were, on average, less satisfied than the European American parents with the descriptive scales often used with younger children, such as "1 = consistently demonstrating, 2 = progressing, and 3 = requires additional attention" (Huntsinger & Jose, 2009, p. 404). Both groups wanted comparative information about their children. We know, however, that information about what individual students have actually accomplished is more helpful for teaching and learning.

The larger point here is that you should not assume that everyone shares one perspective on grades and their meaning. You can expect a diversity of perspectives, and you can expect that whatever the perspective, the person holding it thinks it is in the student's best interests. This book will make recommendations for how to communicate your grading policies to parents and how to give them different kinds of information without confounding the meaning of your grades.

Higher Education Pressures. At least at the high school level, teachers and principals perceive expectations for using grading practices that function well to rank students. College and university admissions directors prefer that high schools use grade-point averages based on weighted grades (Talley & Mohr, 1993). In workshop settings, I have often heard high school teachers state that they must give certain kinds of grades because colleges expect it. I have even heard middle school teachers say that they must give certain kinds of grades because parents want to be sure their children will be ready to gain admission to selective colleges and universities. To be honest, I think some of those teachers were copping ...