![]()

Chapter 1

Why Talk Is Important in Classrooms

Aldous Huxley (1958) once wrote, "Language has made possible man's progress from animality to civilization" (p. 167). In doing so, he effectively summarized the importance of language in humans' lives. It is through language that we are civilized. One could argue that nothing is more important to the human species than that. But Huxley wasn't done there; he continued by explaining the value of language:

Language permits its users to pay attention to things, persons and events, even when the things and persons are absent and the events are not taking place. Language gives definition to our memories and, by translating experiences into symbols, converts the immediacy of craving or abhorrence, or hatred or love, into fixed principles of feeling and conduct. (p. 168)

Language, in other words, is how we think. It's how we process information and remember. It's our operating system. Vygotsky (1962) suggested that thinking develops into words in a number of phases, moving from imaging to inner speech to inner speaking to speech. Tracing this idea backward, speech—talk—is the representation of thinking. As such, it seems reasonable to suggest that classrooms should be filled with talk, given that we want them filled with thinking!

A Brief History of Classroom Talk

Academic discourse has always been part of the classroom. Teachers have long understood the importance of using language to transmit ideas. In the early history of education, teachers talked for most of the instructional day while students were quiet and completed their assigned tasks. Students were expected to memorize facts and be able to recite them. Remember that in most classrooms of the late 1800s, the age range was very diverse. In the same classroom, teachers might have students who were 5 or 6 years old and others who were 15 to 18. Talking by students was not the norm. In fact, students were punished for talking in class, even if the talk was academic!

Over time, educators realized that students had to use the language if they were to become better educated. As a result, well-intentioned educators called on individual students to respond to questions. Teachers expected them to use academic language in their individual responses, and as students spoke, teachers would assess their knowledge. Consider the following exchange from a 3rd grade class. As you read it, think about how much academic language was used:

Teacher: I was thinking about the life cycle of an insect. Do you remember the life cycle we studied? Malik?

Malik: Yes.

Teacher: What was the first stage in the life cycle? Jesse?

Jesse: They was born?

Teacher: Yes, things are born, but think about the life cycle of insects. Let's try to be more specific in our thinking. What is the first stage in the insect life cycle? Miriam?

Miriam: Eggs.

Teacher: Yes, insects start as eggs. Then they change and develop. They become larva after eggs, right? And then what? What happens to them after they are larva? Adrian?

Adrian: They are adults.

Teacher: They do eventually become adults, but there is a step missing. What is the step between larva and adults? What is that stage of the life cycle called? Joe?

Joe: Mature larva?

Teacher: Yes, there are two kinds of larva in the life cycle of some insects. But what I was thinking about was what happened to them after the larva before they become adults. Mariah?

Mariah: Nymph?

Teacher: Now we're talking about the three-stage cycle for some insects. Do the insects that change into nymphs come from larva? Let's look at our two posters again. Remember these? There is a three-stage process and a four-stage process. Let's study these again.

Let's spend a few minutes analyzing this classroom exchange. First, it's not unlike many of the whole-class interactions we've seen, especially in a classroom where the students are obviously having a difficult time with the content. One student at a time is talking while the others listen or ignore the class. Second, the teacher is clearly using a lot of academic language, which is great. We know that teachers themselves have to use academic discourse if their students are ever going to have a chance to learn. Third, the balance of talk in this classroom is heavily weighted toward the teacher. If we count the number of words used, minus the student names, the teacher used 190 words, whereas the students used 11. This means that 94 percent of the words used in the classroom during this five-minute segment were spoken by the teacher. In addition, if we analyze the types of words used, half of the words spoken by the students were not academic in nature. That's not so great. Students need more time to talk, and this structure of asking them to do so one at a time will not significantly change the balance of talk in the classroom.

As you reflect on this excerpt from the classroom, consider whether you think that the students will ever become proficient in using the language. Our experience suggests that these students will fail to develop academic language and discourse simply because they aren't provided opportunities to use words. They are hearing words but are not using them. We are reminded of Bakhtin's (1981) realization: "The world in language is half someone else's. It becomes 'one's own' only when the speaker populates it with his own intention, his own accent, when he appropriates the word, adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention" (pp. 293-294). In other words, if students aren't using the words, they aren't developing academic discourse. As a result, we often think we've done a remarkable job teaching students and then wonder why they aren't learning. The key is for students to talk with one another, in purposeful ways, using academic language. Let's explore the importance of talk as the foundation for literacy next.

Talk: Building the Foundation for Literacy

Wilkinson (1965) introduced the term oracy as a way for people to think about the role that oral language plays in literacy development, defining it as "the ability to express oneself coherently and to communicate freely with others by word of mouth." Wilkinson noted that the development of oracy would lead to increased skill in reading and writing as users of the language became increasingly proficient—as James Britton (1983) put it so eloquently, "Reading and writing float on a sea of talk" (p. 11).

Put simply, talk, or oracy, is the foundation of literacy. This should not come as a surprise to anyone. We have all observed that young children listen and speak well before they can read or write. Children learn to manipulate their environment with spoken words well before they learn to do so with written words. It seems that this pattern is developmental in nature and that our brains are wired for language. Young children learn that language is power and that they can use words to express their needs, wants, and desires.

The problem with applying this developmental approach to English language learners and language learning in the classroom is that our students don't have years to learn to speak before they need to write. Historically, teachers did not introduce English language learners to print until they had developed their speaking skills—a misguided approach that does not take into account the fact that, in developing their primary language, English language learners have already learned much about language, including the role that it plays in interacting with others. At the other end of the spectrum of instructional practice, many teachers did not provide any oral language instruction because they believed that their students needed to develop reading proficiency (and make adequate yearly progress) as soon as possible.

Instead of this either/or approach, English language learners need access to instruction that recognizes the symbiotic relationship among the four domains of language: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Clearly, students must reach high levels of proficiency in reading and writing in order to be successful in school, at a university, and in virtually any career they may choose. We know that it takes time to reach those levels. We know that opportunities for students to talk in class also take time. So, given the little instructional time we have with them, how can we justify devoting a significant amount of that time to talk? We would argue, How can we not provide that time to talk? Telling students what you want them to know is certainly a faster way of addressing standards. But telling does not necessarily equate to learning. If indeed "reading and writing float on a sea of talk," then the time students spend engaged in academic conversations with their classmates is time well spent in developing not only oracy but precisely the high level of literacy that is our goal. In Chapter 3 we will explore how we can maximize use of instructional time to that end.

Talk in the Average Classroom

Classroom talk is frequently limited and is used to check comprehension rather than develop thinking. Consistent with the example from the beginning of the chapter, researchers have found that teachers dominate classroom talk. For example, Lingard, Hayes, and Mills (2003) noted that in classrooms with higher numbers of students living in poverty, teachers talk more and students talk less. We also know that English language learners in many classrooms are asked easier questions or no questions at all and thus rarely have to talk in the classroom (Guan Eng Ho, 2005). Several decades ago, Flanders (1970) reported that teachers of high-achieving students spent about 55 percent of the class time talking, compared with 80 percent for teachers of low-achieving students.

In addition to the sheer volume of teacher talk in the classroom, researchers have identified the types of talk that are more and less helpful. For example, Durkin's (1978/1979) seminal research on comprehension instruction confirmed that teachers rely primarily on questioning to check for understanding. Questioning is an important tool that teachers have, but students also need opportunities for dialogue if they are to learn. And, unfortunately, most questioning uses an initiate-respond-evaluate cycle (Cazden, 1988) in which teachers initiate a question, a student responds, and then the teacher evaluates the answer. Here is an example from a 7th grade social studies discussion of a reading on ancient Mesopotamia:

Teacher: What did the Sumerians use to control the Twin Rivers? (initiate)

Justin: Levees? (respond)

Teacher: Right. (evaluate) And why did the Sumerians want to control the Twin Rivers? (initiate, again)

The problems inherent in this type of approach are multiple. First, in a classroom where we want students to talk—to practice and apply their developing knowledge of English—only one student has an opportunity to talk, and, as we see in this example, that talk does not require the use of even one complete sentence, let alone extended discourse. In a classroom where we want students to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate, neither does this type of interchange require them to engage in critical thinking. Instead, they may become frustrated as they struggle to "guess what's in the teacher's head" or become disengaged as they listen to the "popcorn" pattern of teacher question, student response, teacher question, student response, and so on. Last, in a classroom where assessment guides instruction, with each question the teacher learns that one student knows the answer but can make no determination regarding the understanding of the other 29 students in the classroom.

In sum, talk is used in most classrooms but could be more effectively used to develop students' thinking. Teachers must take into account their English language learners' current proficiency levels when planning instruction.

Differences Among Students

One of the most important things to recognize about teaching English language learners is that they are not a monolithic group. They differ in a number of important ways, including the following:

Linguistic. Although Spanish is the most common second language in the United States, students in a given school district might speak more than 100 different languages. These languages differ in their pronunciation patterns, orthographic representations, and histories—and thus in the ease with which students can transfer their prior knowledge about language to English.

Proficiency in the home language. Students who speak the same language and are in the same grade may have very different levels of academic language proficiency in their home language depending on such factors as age and prior education. The development of a formal first language facilitates learning in additional languages.

Generation. There are recognized differences in language proficiency for students of different generations living in the United States. First and second generations of English language learners differ in significant ways, including the ability to use English at home. Because protracted English language learners born outside the United States attempt to straddle their old world and the new world in which they live, they experience greater difficulty in developing English proficiency.

Number of languages spoken. Some students enroll in schools having mastered more than one language already and thus have gained a linguistic flexibility that can aid in learning additional languages. Others have spoken one language at home for years, and their exposure to English is a new learning experience.

Motivation. Students differ in their motivation to learn English depending on their migration, immigration, or birthplace. Immigrant families leave their homelands for a variety of reasons—political and economic are perhaps the most common. Many of our students have left loved ones behind, along with a familiar and cherished way of life. Some even hope to return when a war is ended or when the family has enough money to better their life in their home country. These students may not feel a great need to become proficient in a language they don't intend to use for very long.

Poverty. Living in poverty and experiencing food insecurity have a profound impact on learning in general and language learning in particular. Simply said, when students' basic needs are met, they are more likely to excel in school.

Personality. Some students are naturally outgoing and verbal; others are shy or prefer more independent activities. Some are risk takers who are not afraid to make mistakes; others want their utterances to be perfect. These differences in personality can lead to differences in the rate at which students gain proficiency in listening and speaking or reading and writing.

Levels of Proficiency

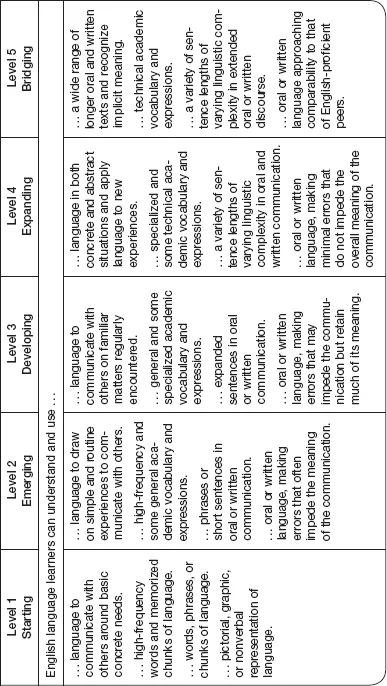

Having acknowledged various differences among students, we also recognize the need to cluster them into levels of proficiency for instructional purposes. There are a number of ways to do this, but we have chosen the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) levels: Starting, Emerging, Developing, Expanding, and Bridging (TESOL, 2006). Figure 1.1 provides an overview of each of these proficiency levels, and they are summarized here as well:

Figure 1.1. Performance Definitions of the Five Levels of English Language Proficiency

Source: TESOL (2006), PreK-12 English Language Proficiency Standards: Augmentation of the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) Consortium English Language Proficiency Standards (Alexandria, VA: Author), p. 39. Used with permission.

Starting. At this entry level, students have virtually no understanding of English and do not use English to communicate. They might...