![]()

Chapter 1

Planning with Purpose

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Did you know that a disproportionate number of skiing accidents happen during the fourth, fifth, or sixth time a person goes skiing? When we first heard this, we were surprised, as we thought more injuries would occur during a novice skier's initial outings. Alternatively, we could see how experienced skiers might get hurt more frequently because they are taking on challenging slopes. But the ski instructor who told us this explained that novice skiers with a handful of trips under their belt know just enough to get themselves hurt … and not enough to prevent it.

As novice teachers, we have all had a similar moment of reckoning. Perhaps it occurred during your second or third year in the profession. The daily jitters from constantly feeling unsure had faded, and you had begun to amass a string of successes. And then you got a bit reckless. You were confident you could wing it and decided not to devote quite as much time to planning as you had previously. After all, you had taught this content once or twice before, and the experience had left you feeling more surefooted.

And then it happened. You tried to teach the lesson, but your students were unclear about the content and began asking questions you were unable to answer. Or you had difficulty linking the new information to the unit of study, and students grew restless. Or the principal came into your classroom during a learning walk and asked you about your formative assessment plan. Whatever the particular circumstances on your day of reckoning, you learned a vital lesson: planning is critical to the success of a lesson. That humbling moment reminded you that you didn't know nearly as much about teaching as you thought you did.

Expert educators have learned that careful planning is key to advancing student learning. For this reason, we begin our focus on high-quality teaching by discussing Planning with Purpose, the first component in the FIT Teaching Tool. To paraphrase the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland, if you don't know where you are going, any road will take you there. Without a clear plan, teachers and students may get somewhere, but it may not be where they needed to go.

Planning with Purpose begins with intentionality. By that we mean that unit design should provide students with the necessary frame to link what they are learning to existing and new knowledge. It should promote transfer. This intentionality is represented in the FIT Teaching Tool as the first factor of the Planning with Purpose component: Learning Intentions and Progressions. A second factor in this component is the teacher's ability to identify short-term success criteria and to plan strategically for how evidence of progress will be collected: Evidence of Learning. Rounding out the planning component is attention to planning learning experiences that will be worthwhile and coherent for learners: Meaningful Learning. We begin with the first factor, Learning Intentions and Progressions.

Factor 1.1: Learning Intentions and Progressions

Planning begins with identifying the learning intentions of the unit under study and then continues with creating a series of lessons that will ensure that students develop proficiency in the content being investigated. In this chapter, we focus on the planning that teachers do to ensure that students achieve high levels of success. In subsequent chapters, we focus on the enactment of the plans as well as the ways in which these plans are modified as students respond, or fail to respond, to the instruction. Remember, hope is not a plan. Students deserve well-planned and sequenced lessons that build on their strengths and address their needs. To our thinking, the Learning Intentions and Progressions factor includes identifying transfer goals, building schema through links to important themes or problems, and crafting content and language learning intentions that are lesson specific.

The following discussions of each of these ingredients include the corresponding rubrics that are part of the FIT Teaching Tool and that describe the four levels of teacher growth—Not Yet Apparent (NYA), Developing, Teaching, and Leading—explained in the Introduction. (Similar discussions and rubrics appear in Chapters 2 through 5, which cover the other four components of the tool.)

1.1a: Identifying transfer goals

NYA

The teacher does not consider transfer goals during planning.

Developing

The teacher identifies transfer goals but does not use them to align plans for student application and assessment.

Teaching

The teacher plans with grade- or course-appropriate transfer goals in mind, and uses them to align activities and assessments.

Leading

The teacher supports colleagues in their ability to plan with grade- or course-appropriate transfer goals in mind and use them to align activities and assessments.

Learning intentions are foundational to everything teachers do with students. The work of planning begins not with listing the isolated facts and skills that students should know but with determining the major conceptual processes that lie at the core of a unit of study. These enduring understandings go well beyond skills (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). For example, learning the Toulmin method for constructing a written argument is a skill; understanding that these elements frame logical and reasoned argument throughout society is an enduring understanding. McTighe (personal communication, 4/13/15) says that teachers know that they are working on a transfer goal when they can complete this sentence: "Students will be able to independently use their learning to…."

Enduring understandings are put into operation through identification of transfer goals. Think of transfer goals as what one does with enduring understandings in novel situations. In other words, they are the expression of understanding. To extend the example from the last paragraph, a transfer goal is that students will be able to write cogent arguments to support claims using formal reasoning and evidence. Learners should be able to do this in a variety of settings. For instance, students may construct a formal argumentation essay in their English class and then use similar features to write an analysis of a document-based prompt in their history course.

Transfer goals are identified through analysis of the standards. If you live in a place where the Common Core State Standards are relevant, some transfer goals are identified through grade-level outcomes. For instance, in 6th grade, students are explaining the relationship between claims and reasons; by 8th grade, this outcome has expanded to include counterclaims and evidence, as well as claims and reasons. McTighe (2014) explains that transfer goals possess the following characteristics:

- They are long-term in nature; i.e., they develop and deepen over time.

- They are performance based; i.e., they require application (not simply recall).

- The application occurs in new situations, not ones previously taught or encountered; i.e., the task cannot be accomplished as a result of rote learning.

- The transfer requires a thoughtful assessment of which prior learning applies here; i.e., some strategic thinking is required (not simply "plugging in" skill and facts).

- The learners must apply their learning autonomously, without coaching or excessive hand-holding by a teacher.

- Transfer calls for the use of habits of mind; i.e., good judgment, self-regulation, persistence along with academic understanding, knowledge and skill. (p. 1)

As you examine your standards documents, keep these features in mind.

We especially appreciate McTighe's advice concerning "excessive hand-holding" as it speaks to the long-term nature of transfer. It's a lot easier and faster to learn discrete skills than it is to learn how to transfer that knowledge across situations. For example, we might introduce 6th grade students to writing for argument through intentional instruction, including extensive scaffolding in the form of paragraph frames, essay templates, and so on. However, those 6th graders will need much more than a single short unit on argumentative writing to craft strong written and spoken arguments in other disciplines and situations. Transfer goals require an investment of time to create opportunities throughout the year for students to apply this knowledge. It is for this reason that Wiggins and McTighe (2005) advise that transfer goals consist only of those that will be assessed. Although argumentative writing involves lots of important skills and information, not all of these need to be assessed.

A group of 11th grade teachers kept these characteristics of transfer goals in mind as they planned an interdisciplinary unit on writing for argument. English teacher MaryAnn Gates, chemistry teacher Christina Hobson, and history teacher Antoni Caro used the standards in their content areas to identify argumentative writing as a transfer goal common to their disciplines. To foster transfer, they planned a two-week unit in September to expose their students to the use of argument in each content area, and they created assignments to promote application. Ms. Gates taught elements of argumentation in her English class, while Mr. Caro focused on the use of argument in excerpts from U.S. Supreme Court decisions. Ms. Hobson used science articles to analyze evidence that supported and refuted claims. In each course, students wrote short argumentative essays that aligned with the content they were learning. It is important to note that the team understood that this unit alone would not be sufficient, so they mapped out a series of competencies throughout the year that would continue to press students to use formal reasoning in their writing.

This example is an excellent illustration of a Teaching level of growth for the ingredient of identifying transfer goals. However, the three teachers advanced to a Leading level through Doug's support. With his encouragement, they individually shared their processes with other faculty at the school, using short videos they each made to capture their instruction. They also discussed their efforts and success at a professional learning session, where they spoke to the rest of the faculty about their work and their students' progress. We note this to reiterate that achieving Leading levels is not dependent on job title, and that sharing experiences with an eye toward developing the capacity of others is within the reach of any skilled teacher.

A teacher at the Developing level of growth is applying knowledge of transfer goals but is not yet sustaining attention to them systematically. George Diaz was developing his ability to use transfer goals. He attended a summer institute on curriculum development after his first year as a kindergarten teacher. "I can see now how transfer goals are essential in learning how to read," he told his induction coach. He abandoned the "letter of the week" approach he had used the previous year because he realized that it sacrificed transfer in favor of discrete skills. After reexamining the kindergarten expectations, he identified using letter-sound relationships to decode unfamiliar words as an important transfer goal. Near the end of the first quarter, he met again with the induction coach, who asked him about how he was assessing his students on their progress toward this transfer goal. Mr. Diaz acknowledged that although he had completed several screening assessments during the first weeks of school, he had not yet revisited them. "I realize I should," he said. "I said this was important, but then that means I also have to monitor [it]." He and his coach scheduled several assessments to administer during the second quarter so Mr. Diaz would have a better sense of his students' progress. "I can't do a great job planning if I don't know how they're doing," he said.

Unfortunately, not all teachers have identified transfer goals, and some simply teach individual lessons. Marco Parma was one such teacher. Despite having taught for several years, he had never considered transfer goals and thus regularly performed at the Not Yet Apparent level. Talking with a colleague who had focused on transfer goals piqued Mr. Parma's interest. This colleague regularly brought examples of student work to their collaborative planning team meetings, and the work was far superior to that of Mr. Parma's students. This colleague did not brag about her students' performance; instead, she engaged in reflective conversations about their learning. Mr. Parma planned a time to talk with her further about implementing transfer goals so that he could determine what he wanted his students to know and be able to do in unique situations.

1.1b: Linking to theme, problem, project, or question

NYA

The teacher does not link learning intentions to themes, problems, projects, or questions.

Developing

The teacher identifies learning intentions that are minimally linked to themes, problems, projects, or questions.

Teaching

The teacher identifies learning intentions that are linked to themes, problems, projects, or questions.

Leading

The teacher supports colleagues in their ability to identify learning intentions that are linked to themes, problems, projects, or questions.

Themes, problems, projects, and questions can make the learning journey as interesting as the destination. They are used to foster inquiry and curiosity about the unit of study. The use of such devices builds schemas to transform isolated bits of information into a unified and flexible whole.

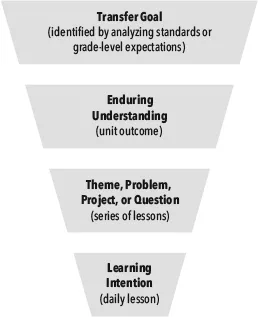

Themes, problems, projects, and questions work like a magnet to draw information together in ways that build schemas. Students might have an array of isolated facts about a topic but no real way of gathering them together. Think of a bunch of paper clips scattered across a desktop. If you wave a large magnet near them, the paper clips form a unified whole. Suddenly, what seemed like a disordered mess is transformed. Using themes, problems, projects, and questions as inquiry approaches serves as an important way to gather daily learning intentions into schemas that move students closer to attaining enduring understandings, which, in turn, form the basis for transfer goals (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 | A Focus on Learning

The professional learning communities at Grant Middle School were studying the importance of oral language in learning, and they decided to base their discussion on an issue of Educational Leadership focused on talking and listening. The mathematics department selected an article titled "Talking About Math" (Hintz & Kazemi, 2014) for their discussion. The PLC members took turns leading, and this time it was Kathy Ellington's turn. A few days before the meeting, she had sent copies of the issue to her colleagues, along with two sets of questions to spur their thinking as they read:

- The authors state that "[d]ifferent discussions serve different purposes, and the discussion goal acts as a compass as teachers navigate classroom talk" (p. 37). How do you match discussion protocols/routines with your learning intentions? How do you know you got it right? How do you know when there's a mismatch?

- "The ways teachers and students talk with one another is crucial to what students learn about mathematics and about themselves as doers of mathematics" (p. 40). What do you observe among your own students? Do they see themselves as "doers of mathematics"?

Ms. Ellington's use of questions helped her colleagues organize their thinking beyond simply summarizing the article. By planning thought-provoking questions for a collegial conversation, she set the stage for a discussion of the link between content knowledge and students' use of language and demonstrated her Leading level of growth for this ingredient. Later in the year, when Ms. Ellington met with a supervisor, she used this example as an artifact of her work leading colleagues.

Another member of Ms. Ellington's school, 7th grade social studies teacher Lyn Jeffries, was at the Teaching level of growth. Her students were studying Islamic civilizations in the Middle Ages. She identified an enduring understanding that human migratory patterns ensure that a culture spreads rapidly throughout a region. Her transfer goal was for her students to see patterns between historical and current events as they relate to the impact of human movement. She planned a unit of instruction designed to ensure that her students would reach this understanding by organizing learning experiences around a thought-provoking question. Her students engaged in an online investigation using the question "How did the Hajj pilgrimage shape politics in places like Spain and Timbuktu?" Over the course of two days, students worked collaboratively in small groups to address the question and share information with their peers. The question was posted in a prominent place in the classroom. In addition, students saw the question on their course home page each time they logged into th...