![]()

Chapter 1

Why Active Learning Matters

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Standards. Pacing guides. Textbooks the size of an 11-year-old. High-stakes tests. Changing teacher evaluation tools. A tremendous amount of responsibility and accountability rests on educators' shoulders. The weight and pace of the curriculum loom. All of those learning targets and so little time—how can all of this content in teachers' brains and resources be successfully transmitted to students' heads?

So, we go home and read and annotate. We synthesize and carefully prioritize gathered information. Systematically, we decide what to leave in and what to leave out. We summarize difficult information into our own concise language. A presentation emerges, complete with perfectly cropped pictures that enhance the content story. We have created evidence of solid progress of our learning target. Our work is then pushed out to students, who are clearly underwhelmed by our late-night efforts on their behalves. Students take notes and nod. At the end of the week, students take a test and largely repeat the information back. Once again, we have inadvertently outworked, outthought, outparticipated, and probably even outlearned our students.

They sit. We stand. We talk. They stare. Our feet hurt. Theirs seem fine.

This book is about getting more out of our students. More connectivity to the content. More purposeful, visible, active work that demonstrates progress on learning targets. More student autonomy, more critical thinking, more effective communication, more reasoning. It's also about thinking about work differently. Because sharing a sticky note plot summary with a partner is work—it's just such engaging work that every student will likely jump in. Creating a press release of new lunchroom options is work—it's just relevant work. Sorting fractions from smallest to largest with a partner is work, too—it's just fun work. Rolling a cube with thought-provoking economic questions with a team is also work—it just happens to be something all of our students typically love doing. That four-letter word "work" can actually be most rewarding.

Shifting more active academic autonomy onto students' shoulders requires a different type of work on our parts, too. One of the most thoughtful decisions in creating lessons in which students are the most active participants in the learning process is deciding what needs to be explicitly taught to be successful and what students can develop and create on their own. With this movement to more active, student-centered learning is the tenet that students are not just learners but also collectors and presenters of evidence. They communicate with us via their ongoing, minute-by-minute work. "Here is where I am on this learning target. Where do I need to go from here?" And their work—their evidence of learning—should change over the course of a lesson, from emerging knowledge in the opening minutes to a deeper understanding at the close.

The phrase "active learning" or "student-centered learning" can potentially conjure images of an unguided classroom in which students are sort of figuring everything out on their own, but it's quite the opposite. In fact, according to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006), instruction that is too unguided and does not provide critical pieces that students need to learn can be counterproductive and even reduce achievement. The strategies employed in this book fit into an instructional framework that thoughtfully builds time at appropriate junctures for students to process what they are learning. Throughout the lesson, students' work will visibly develop and deepen, and by the end of class, all students will have something to "show" for their work today. Creating more active learners does not imply that we are less active as teachers. It's about creating a balance between teachers' roles in learning and our students' responsibilities.

And while this book is largely focused on the "how" part of getting students actively involved in their work, it's important to begin with some of the "whys" because many short- and long-term benefits can be gleaned from pivoting to a more student-centered classroom.

Active Student Learning Can Lead to Higher Achievement

Definitions abound for both "active learning" and "student-centered learning," but a central theme is this: Less time and focus are allocated for teacher presentation (and talking in general), and a greater emphasis and time are spent on having students develop, read, solve, create, analyze, and summarize—and a larger share of those rigorous verbs falls on students' capable shoulders. In a traditional classroom, information largely flows from teacher to students. Teachers are highly engaged as they move, write, explain, erase, question, rephrase, and answer. In an active, student-centered classroom, information flows in both directions, and students are highly active. They are not passive receivers of information. Additionally, lessons are created with designated work time for students to absorb, collaborate, and create, so that students actively working takes a bigger piece of class time than teacher presentation.

Teacher talk time is a problem. Hattie (2012) indicates that somewhere between 70 and 80 percent of class time is occupied by teachers talking and that the older students are outtalked even more than students in younger grades. Researchers Tsegaye and Davidson (2014) found in their study of language teachers that it was even higher, with an average of 83.4 percent classroom discourse belonging to teachers and 16.9 percent to students. This is not a new concern. In 1969, Cross and Nagle discussed the problem of secondary English teachers talking three times more often than their students. But what's really interesting is they cite research from 1912 bemoaning the same problem, specifically that teachers talk about 64 percent of the time, less than Hattie's more current estimations. The question of whether teachers are talking at a higher percentage today than in 1912 makes for interesting discussion but is not the biggest concern. The more troubling aspect is that students as a group only own somewhere around 16.9–36 percent of the talking. With that talk being divided by, say, 28 students in a class, the amount that students are getting to talk about their learning is so minimal that it puts into question our entire instructional framework.

The trouble with an imbalance of teacher-student talk is what happens to learning. In a very interesting study by Gad Yair (2000), 865 students in grades 6–12 in all academic content areas wore wristwatches programmed to beep throughout the day. When the watches beeped, students responded to questions about what they were doing: their level of engagement, mood, and thoughts. Not surprisingly, there was a direct connection between levels of student engagement and instructional methods. The lowest level of engagement, 54.4 percent, was when teachers were talking (p. 256). Even though lecture was the least engaging, it was actually the dominant delivery method (p. 259).

In contrast, students were the most engaged when they were working in labs (73.7 percent) and in groups (73 percent) (Yair, 2000, p. 256). Even though these methods yielded the highest engagement levels, they were the least prevalent, only 8 percent of the time (p. 260). So, the methods that worked the best for learners were used the least, and the method that was the least engaging was used the most.

Similarly, in a study of 8th graders studying water quality standards in Indiana, Purdue researchers found that hands-on, problem-based learning yielded greater student success (Riskowski, Todd, Wee, Dark, & Harbor, 2009). Eighth graders were all taught the same science standards on water quality but with different methods. Half of the 8th graders participated in a more traditionally taught lesson that was roughly 60 percent lecture, 20 percent handouts, and a final project worth 20 percent. The other group of students experienced a more active approach, with less than 10 percent of their time listening to teachers talk. The bulk of the active group's time was spent working in cooperative teams designing and building a water purification system. At the end of the unit, students in the active classroom scored an average of 77 points on a 100-point exam. The traditionally taught class scored an average of 57. An encouraging aspect of their study was the broad spectrum of students positively influenced: Traditionally underperforming students, including English language learners, shared in this rise.

But what about older students? They're able to learn material by sitting still and listening, right? In an analysis of 225 studies on active versus lecture-type classrooms in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) undergrad college courses, researchers in a 2014 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Freeman et al., 2014) made this case: A lot more STEM grads would be produced if traditional lecturing were replaced with more active learning teaching methods. Why? Because failure rates and test scores varied significantly between the two instructional approaches. Their work revealed that the failure rate among students in more active classrooms was 21.8 percent, compared to 33.8 percent in traditional classes—a 55 percent increase.

Similar effects were reported by chemical engineering professors Bullard, Felder, and Raubenheimer (2008) at North Carolina State University. In a sophomore course with a reputation for "weeding" students out of the program due to high failure rates and low grades, there were two sections. One was taught via traditional lecture; the other section incorporated active learning techniques such as cooperative learning and greater opportunities for feedback. Essentially, the active class broke up the teacher talk, gave students time to process information with others, and incorporated team exercises. Over the course of five years, students with lower GPAs in the active section outperformed other students with lower GPAs in the lecture format class, even though the active classroom had more students. Active learning, the professors suggest, helped boost weaker students, resulting in less failure and fewer dropouts in the program.

Short Bursts Are Better for Our Brains

The unfortunate reality is that students (and adults) can only listen for a short period of time. After that, they are pretty much pretending. Even students in college—students who have been largely successful in grades K–12, have passed entrance exams, and have healthy enough GPAs to be in college—can be truly attentive for just a short period of time during teacher talk. Hartley and Davies (1978) purport that students could recall about 70 percent of what was taught in the first 10 minutes of a presentation but only a sparse 20 percent of the last 10.

When I am planning with teachers in schools, we utilize Eric Jensen's (2005) guidelines for direct instruction (Figure 1.1). These specify that even high school seniors and adults can only pay attention to spoken instruction for about 15 minutes, with elementary students ranging between just 5 and 12 minutes. Placed in the context of long school days sitting in hard desks trying to pay attention to teachers talking, it provides us with some understanding of students' frequent requests to get water, see the nurse, go to their lockers, talk to the counselor, check their phones, call their congressperson—anything to relieve the frustration and fatigue welling up in them. Their behavioral feedback is signaling to us: "We need a break to do something with this information. Please stop talking!"

Figure 1.1. Guidelines for Direct Instruction of New Content

Grade Level: Grades K–2

Appropriate Amount of Direct Instruction: 5–8 minutes

* * *

Grade Level: Grades 3–5

Appropriate Amount of Direct Instruction: 8–12 minute

* * *

Grade Level: Grades 6–8

Appropriate Amount of Direct Instruction: 12–15 minutes

* * *

Grade Level: Grades 9–12

Appropriate Amount of Direct Instruction: 12–15 minutes

* * *

Grade Level: Adult learners

Appropriate Amount of Direct Instruction: 15–18 minutes

Source: From Teaching with the Brain in Mind (p. 37), by E. Jensen, 2005, Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Copyright 2005 by ASCD.

Understanding the short time that learners can actually just sit and listen to direct instruction creates an urgent need to be thoughtfully judicious about the portion of the lesson that is explicitly taught via presentation. What is it about this new concept that requires explaining and modeling? How can the onslaught of information be distributed throughout the lesson to provide for more student interaction with the concept? How can the lesson be more balanced in terms of students doing more of the thoughtful work?

For example, in a lesson with the learning target of "How can you make or lose money in the stock market?" the teacher mini-lesson might focus on how to read the stock market section of the newspaper and detail how prices rise and fall. This is a complex concept that lends itself to teacher expertise rather than having students just read text. Next, students take the active role to demonstrate understanding of the concept. For example, each student in a four-person group could select a company's stock to research. Next, they would report to their team about what they have learned and make predictions for their stock's future. Now, individually, each student could select one of the four stocks for her own portfolio and make her case. Teaching is still going on as students are working but in a more advisory and facilitative capacity. Listening to their conversations and seeing their work visibly develop provide opportunities for feedback. By monitoring the balance of teacher talk and student talk, we successfully moved more of the really interesting work onto students' shoulders.

Teachers may feel a panicked urgency to push through the curriculum to meet a pacing guide. But if listening to someone talk was the most effective way to learn, well, all of our students would be soaring academically. In a training session recently, a high school teacher remarked that his classes were just too short to do "hands-on" kinds of strategies. But if students can't help but tune out teacher talk after just a few minutes, what's the point in continuing to ramble on?

For male students in particular, who, according to Gurian and Stevens (2004), constitute 90 percent of all discipline referrals and fail and dropout at higher rates, this martialing through via teacher talk is especially problematic. Girls get bored, too, but are more likely to at least stay upright and continue taking notes. Boys have more of a tendency, due to the makeup of their brains, to stop working entirely, fall asleep, or tap their pencils in an attempt to stay awake (Gurian & Stevens, 2004). The more teachers talk, the more boys' brains tend to fall into a state of rest.

New assessments are calling on students to apply what they have learned, analyze, and explain their reasoning. Students need time in class to authentically and collaboratively hone these higher-order skills. Marzano and Toth (2014) explain that the traditional teacher-centered pedagogy has limitations. Rather than increasing student ownership and independence, students may be spending the bulk of their time just listening. In the traditional teacher-led model, teachers carry too much of the thinking load. If learners spend most of their time at these lower levels of thinking, students may find themselves unprepared for more complex assessment tasks.

Developing Visible Student Work Provides Opportunities for Feedback

Hattie (2009) calls feedback the most "powerful single influence enhancing achievement" (p. 12). After this pronouncement, he expounds on the critical nature of creating learning situations that promote this feedback. In effect, students are giving us feedback about our lessons via their ongoing work. Based on what teachers observe, feedback to students ensues. In the active classroom, we can see their work developing in a highly open manner and respond.

Conversely, in a traditional classroom, students often develop work—evidence of their progress—and place it in a bin. Teachers gather the piles of evidence, rubber band them securely, and organize them in piles. A few get covertly graded during a faculty meeting, with the bulk winding up under a car seat or on the kitchen table at home. Over the course of the next couple of days, the pile at home gets smaller; unfortunately, more piles are developing in the bins at work. By the time they are returned, that learning goal has passed. Students roll their eyes and inquire, "Do we need to keep this, or can it go in the trash?"

It's difficult to provide quick and effective feedback to students in a whole-group setting. Some students may need that additional clarification, but others do not, and we may have inadvertently interrupted every other student's thinking. Similarly, the desk-to-desk model of feedback has drawbacks. First, there is simply not enough time. Students in desks 20-something wait and wait for help. By the time they are receiving feedback, students in the first desks may be in a holding pattern waiting for help again. Plus, this risks communicating that the teacher is the keeper of all information, rather than placing more autonomy on students' shoulders. Conversely, a setting in which students are comfortable revealing their work almost minute by minute provides opportunities to answer the three feedback questions Hattie (2009) recommends: "Where are they going?" "How are they going?" "Where to next?"

Having students work in teams or pairs creates a more advantageous teacher-to-pupil ratio. Rather than stopping at 28 desks, for example, there are 7 or 14 stops. More importantly, students provide feedback to one another. And, with many tasks, it's appropriate to leave an answer key three feet away from students' work area. They can take a quick peek to self-assess when they get stuck. These three feedback loops, self-assessment, peer assessment, and teacher assessment, Davies (2007) tells us, have the power of multiplying the effects of feedback.

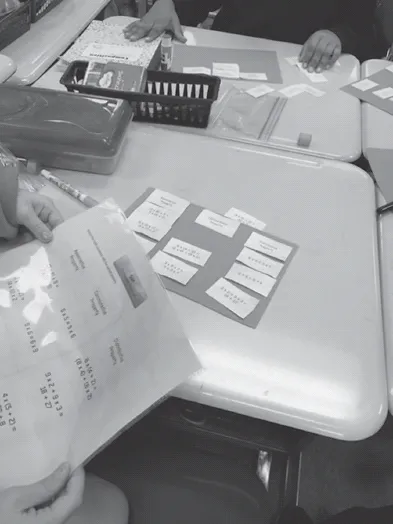

In Figure 1.2 from Acquanette Wallace's classroom, the student is self-assessing her work on a math sort. When she's satisfied with the results, her teacher takes a look with her, and the sort is glued down. This builds student independence and allows teachers to continue working with other students.

Figure 1.2. Student Self-Assessment of Math Sort

Monitoring work as it develops rather than later provides ongoing opportunities to move students upward. In a sense, the work they are creating provides communication to the teacher. "Here is where I am." The work—the task—is what the feedback is about. Here is where you are, and here are some ideas about some adjustments you can make. Their visible work provides us with concrete evidence of the effectiveness of the lesson as well.

Active Learning Can Improve Student Engagement

When one person—be it teacher or student—is in the delivery mode, what's everyone else doing? For example, if one student is at the board solving a math problem, what are the other 27 doing? If one student is re...