![]()

Part 1

Who You Are

![]()

Chapter 1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

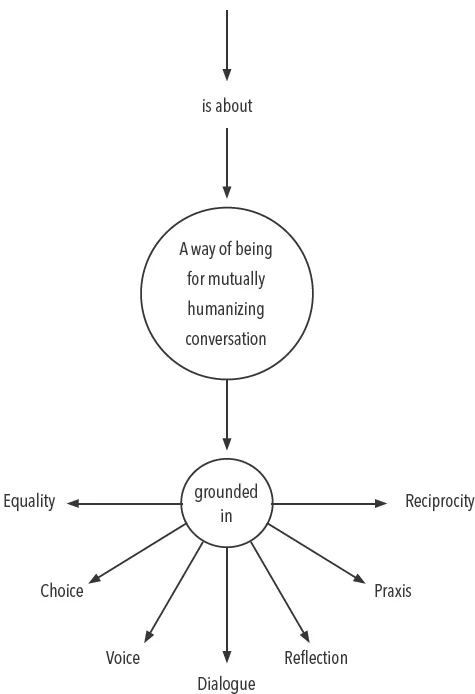

Learning Map for Chapter 1

The Partnership Principles

The Partnership Principles

When [people] cannot choose, [they] cease to be [people].

—Anthony Burgess

Chandra Edwards was an accomplished, award-winning teacher who chose to become an instructional coach so she could have a bigger impact on students' lives. "If I work with all the teachers in the school," she reasoned, "I can make a difference for a lot of kids."

Chandra didn't receive much professional development on how to be a coach, but she felt she knew quite a bit about effective instruction. She'd gone to workshops based on Marzano's and Hattie's work and even felt a bit nerdy on the subject, since she actually enjoyed reading their research summaries. In her classroom, she used cooperative learning structures like Mix-Pair-Share and Numbered Heads Together, as well as learning maps from my own book High-Impact Instruction (Knight, 2013). She had also attended a lot of training based on Charlotte Danielson's book Enhancing Professional Practice (2007), which her district used to evaluate teachers. Looking ahead to her first year as an instructional coach, she was excited to share what she knew.

Once she got started, however, Chandra was surprised to discover that teachers weren't all that keen to work with her despite all she had to share. She knew teachers were busy—after all, she'd been in the classroom for 18 years herself—so she decided to focus on relationship building with a few of her closest work colleagues. When she asked them if they'd do her a big favor and work with her, they gladly agreed because they liked Chandra.

Chandra was kind of relieved that she was able to ease into coaching. She wasn't sure what she should do once she had people willing to work with her. But she had been a successful teacher, and she assumed coaching would be a similar process. Since she knew about the power of feedback, she decided to observe teachers, share her observations about what seemed to be working well in their classrooms, and possibly suggest one or two areas for improvement. In other words, she'd share "a glow and grow" with every teacher she observed and then maybe talk about strategies they could use to grow their practice further.

Right away, Chandra realized the conversations she was having didn't feel right. For one, she was doing most of the talking, which she knew wasn't the way to coach. But most troubling was the fact that these teachers, who had gone out of their way to support her, didn't seem to want to hear what she had to say. "It feels like they're looking right through me when I talk," she told a friend.

From there, things got worse. Her friends thanked her for her time, but they didn't implement her suggestions and said they didn't have time to work with her anymore. At the same time, Chandra's principal expected to see results and wanted her to work with some teachers who were really struggling. "Those teachers need to get better quickly," the principal told her, "because they are letting down their students and the school with their ineffective teaching."

The principal was right to say the teachers were struggling. The classes Chandra observed were boring and confusing. But how could she help the teachers if they didn't want to work with her? Sometimes they wouldn't even look her in the eye when she gave them feedback. Chandra came to hate having these conversations, yet she also felt pressure to show results. Her position was grant-funded, and when the grant was gone, her job would be gone, too, if she didn't clearly show that she was making an impact.

In an effort to turn things around, Chandra asked her principal to make teachers attend workshops she was holding before school every other Wednesday. But these compulsory workshops turned out to be agony for both the teachers and Chandra. The teachers made it clear that they didn't want to be there, and their comments during sessions all seemed to be about why the strategies wouldn't work. Chandra pushed harder, explaining why everyone should do what she was saying, and the teachers pushed back. "Why are these teachers so resistant?" she kept asking herself.

Chandra tried other techniques. She created a weekly email for teachers about effective teaching practices. She conducted walkthroughs of teachers' classrooms, leaving observation notes in teachers' mailboxes. She sat in on meetings of professional learning communities (PLCs). Soon she began to suspect that the teachers didn't like her—and worse still, that she was having no lasting impact on instruction and student learning in her school.

Though Chandra Edwards is fictional, the anecdote above reflects comments I have heard from dozens of instructional coaches about their experiences working with teachers. People go into coaching with enthusiasm, eager but unprepared for the realities of their new role, and then are surprised to find that teachers are less than excited about working with them. If coaches then become more direct in their approach, teachers become even less interested, and eventually the coaches give up.

Teachers like the ones in Chandra's school aren't resisting ideas but, rather, poorly designed professional development. The problem doesn't lie with them, but with underprepared coaches who treat their teachers the way they treat students. Thankfully, by learning about the seven Partnership Principles that are the focus of this chapter, coaches can help ensure that teachers welcome rather than resist the coaching process.

The Partnership Principles are probably the most impactful of all the coaching ideas I've shared over time. I created them by synthesizing theories from education, business, psychology, sociology, cultural anthropology, and philosophy of science—in particular, the works of Richard Bernstein (1983), Peter Block (1993), David Bohm (1996), Riane Eisler (1987), Paulo Freire (1970), and Peter Senge (1990).

I've written about the principles in several other publications, including Partnership Learning Fieldbook (2002), Instructional Coaching (2007), Unmistakable Impact (2011), and The Impact Cycle (2018), and I've summarized them in many articles and books. The truth is, I've written about the principles so much that I can't blame you if you thought, "What? The principles again?" when you saw what this chapter was about. But our conception of the principles has been transformed in recent years by both ICG's own research and new insights gained from the literature. In this chapter, then, I describe a new way of understanding the principles.

What Is a Principle?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a principle as a "fundamental source from which something proceeds … the ultimate basis upon which the existence of something depends" (Oxford University Press, 1981, p. 2303). In other words, principles guide our actions whether we are conscious of them or not. For example, a person who lives by the principle "I want to live a life of service" will act differently than a person who adheres to the principle "I'm only interested in what's good for me." And principles are revealed in our actions more than our words: though you might think you live by the principle "I'm always honest," for example, you may prove otherwise when someone asks, "Did you like my presentation?"

Principles provide us with a theoretical framework for being, but they are also very practical. They help us determine what to do in new or ambiguous situations. For example, if we embody the Partnership Principle of voice (see below) in our behavior, we do our best to talk and act in ways that show our conversation partners we believe their opinions matter.

Principles also help us describe both the person we are and the person we want to be. Though stating aloud that others matter doesn't magically turn us into people who listen with empathy, it does provide us with a starting point, a way to reflect on our practice, and, often, a way to diagnose where we need to do more work so that others see that we respect them, believe in them, and have their best interests at heart.

The Partnership Principles

Equality

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights begins with this statement: "Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…." That same principle drives the approach that I think coaches should take when partnering with teachers. When coaches work from the principle of equality, collaborating teachers feel seen, valued, and respected and believe they are afforded the status they deserve as professionals.

To embrace equality is to believe that no one person is more valuable than any other. As Nelson Mandela said, "The world's problems begin with the notion that some lives are more valuable than others" (Hatang & Venter, 2011). However, this doesn't mean that everyone should be treated the same. People are as unique as their fingerprints, with their own individual sets of strengths, needs, characteristics, and histories, so it would be unfair and ineffective to treat them interchangeably. Indeed, if we work from the belief that everyone is equally valuable, we should feel compelled to support policies and practices that differentiate for each person.

Equality and resistance. In their landmark book Motivational Interviewing (2013), about an approach to therapy that is grounded in the principle of equality, William Miller and Stephen Rollnick write that few people "appreciate … the extent to which change talk and resistance are substantially influenced by counseling style. Counsel in a directive, confrontational manner, and client resistance goes up. Counsel in a reflective, supportive manner, and resistance goes down while change talk increases" (p. 9). When we work from the principle of equality, we see the unique aspects of each person. We don't see others as stereotypes—a new teacher, a special education teacher, a resistant teacher; instead, we see Keysha, Suzanne, or Kurt. We affirm, we show respect, we listen, and, perhaps most important, we remain fully present in conversations because we believe the other person counts.

Saying we believe in equality is easy, but our words can give us away if we don't live up to them. In the many workshops I've led, the way people talk suggests that they are only able to pay lip service to equality as a principle. Questions like "What if the teacher doesn't take my advice?" "What if the teacher's opinion is wrong?" and "What if the teacher picks the wrong strategy to move toward the goal?" are really telegraphing that their suggestions are always superior to the teachers' and that the teachers should always implement them.

While our experience and expertise may enable us to see things that others don't, research suggests that our observations aren't as accurate as we think. Most of us of tend to overestimate the value of our insights, for example (Buckingham & Goodall, 2019). Further, telling people what to do creates dependency by communicating that we don't think they are capable of solving problems on their own.

Equality and moralistic judgment. We violate the principle of equality when we moralistically judge collaborating teachers, thinking or even claiming that they are not as good as we are. In his book The Six Secrets of Change (2008), Michael Fullan describes moralistic judgment, which he calls judgmentalism, as follows:

Judgmentalism is not just seeing something as unacceptable or ineffective. It is that, but it is particularly harmful when it is accompanied by pejorative stigma, if you will excuse the redundancy. The advice here, especially for a new leader, is don't roll your eyes on day one when you see practice that is less than effective by your standards. Instead, invest in capacity building while suspending short-term judgment. (p. 58)

Moralistic judgment contradicts equality by placing others below us. That creates a gap between us and them that kills intimacy and prevents learning. We don't run to get help from someone who will roll their eyes when we talk (and as I've heard Michael Fullan say in his presentations, there are many ways to "roll your eyes" without using your actual eyes).

Avoiding moralistic judgment does not mean avoiding reality. A clear picture of reality is essential for growth and learning. We can talk about reality and avoid judgment by communicating that we respect and believe in the teachers with whom we work. During a conversation based on equality, there is energy, openness, and a mutual sharing of ideas in part because the coach believes teachers should choose their paths for themselves.

Choice

When coaches embrace the principle of choice, teachers make most, if not all, of the decisions about changes to their classrooms. There is freedom in the conversation that isn't possible when coaches try to control what teachers do. When a conversation feels "off" or "out of sync," it is often because collaborating teachers don't feel they are free to say, do, or think what is on their minds.

What the research says about choice. Working from the principle of choice is not just a nice thing to do but a practical necessity. More than three decades of research has shown that telling professionals what to do without giving them a choice almost always results in failure. Researchers such as Teresa Amabile, Regina Conti, Heather Coon, Jeffrey Lazenby, and Michael Herron (1996); Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (2017); and Martin Seligman (2011) all consider autonomy to be essential for motivation. Deci and Ryan characterize the conclusions they've drawn from decades of research as social determination theory—namely, the idea that people feel motivated when they (1) are competent at what they do, (2) have a large measure of control over their lives, and (3) are engaged in and experience positive relationships. The theory posits that the opposite is also true: when people are controlled and told what to do, are not in situations where they can increase their competence, and are not experiencing positive relationships, their motivation will be "crushed" (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 68).

A report from the Institute of Educational Sciences (Malkus & Sparks, 2012) summarizes research showing the importance of teacher autonomy:

Research finds that teacher autonomy is positively associated with teachers' job satisfaction and teacher retention (Guarino, Santibañez, and Daley 2006; Ingersoll and May 2012). Teachers who perceive that they have less autonomy are more likely to leave their positions, either by moving from one school to another or leaving the profession altogether (Berry, Smylie, and Fuller 2008; Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, and Wyckoff 2008; Ingersoll 2006; Ingersoll and May 2012). (p. 2)

Yet despite the important role of choice, research suggests that autonomy is decreasing for almost all teachers (Malkus & Sparks, 2012).

Why choice is important. Choice is essential for at least three reasons. First, top-down models of change usually do not work. Telling professionals what they have to do might yield compliance, but not commitment (Deci & Flaste, 2013). Many educators have experienced top-down initiatives that were rolled out with a lot of fanfare but wound up having little impact on how teachers teach and how students learn.

Second, controlling other people is dehumanizing. As Donald Miller has written, "the opposite of love is … control" (2015). Our ability to make c...