![]()

Chapter 1

Reading and Writing in English Classes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

One of the many features of middle and high schools, and one that has significant instructional implications, is the fact that teachers and their adolescent students do not spend the entire day together. In elementary school classrooms, teachers integrate their reading and writing instruction while teaching content. Although specific periods of the day are set aside for reading and language arts in elementary school, the focus and strategies used throughout the day and curriculum and can be more cohesive.

Does this mean that we would like to see middle and high school students with one teacher for the entire day? Certainly not! We know that middle and high school students need access to teachers who are passionate and knowledgeable about their respective subject areas. We also know that the texts students read across disciplines are more complex, and students often require instruction to access these texts. We do, however, believe that we can learn from the elementary school's ability to create an integrated experience for students.

In Chapter 2 we explore the role that teachers of the content areas (including science, music, math, art, social studies, and physical education) play in adolescent literacy. More specifically, we explore various instructional strategies that teachers and students can use to comprehend content. In addition, we explore the various types of texts that students can and should be reading, and the ways in which teachers can organize their instruction.

However, in this chapter we focus on English teachers. We know that English teachers can improve literacy achievement and that they can do so while addressing their specific content standards. We also know that they cannot create literate students alone and that they must collaborate with their content area colleagues to be successful. The essential question that guides our thinking about English teachers is this:

Are students' reading and writing development and relevant life experiences used to explore literary concepts?

As you read in the Overture, we have identified five major areas that support this essential question. In the sections that follow in this chapter we explore each of these in turn as we consider the role that English teachers can play in improving adolescent literacy and learning. Following this chapter we explore the ways in which content teachers can improve adolescent literacy and learning. We do not believe that English teachers can serve only as literature teachers. As Slater (2004) notes,

The study of literature permeates the English classroom to such an extent that one begins to believe that the purpose and function of English instruction in America is to train the next generation of literary scholars rather than to provide an increasingly diverse student population with a knowledge base and strategies necessary to help all students achieve the compelling goal of high literacy. (p. 40)

A Focus on Themes

We'll start by challenging a tradition of the English classroom—the whole-class novel. This one-size-fits-all approach to the curriculum does not respond to the unique needs, strengths, or interests of adolescents. Frankly, it does not work in reaching the goal of improving literacy achievement and creating lifelong learners and readers.

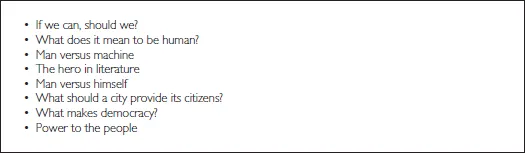

Area 1: English Language Arts Class

1. Are students' reading and writing development and relevant life experiences used to explore literary concepts?

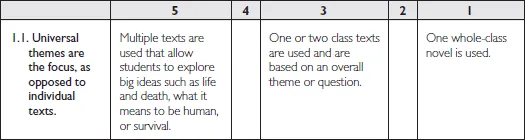

Imagine this English classroom. All the students are sitting in rows with their copies of Romeo and Juliet open. Their teacher reads aloud. After a few minutes, the teacher calls on a student who begins to read where the teacher left off. Once the student has read the page, he calls on more students until they have read for 25 minutes. At this point the teacher turns on the TV and the class watches a video of the section of the book they've just read—another 15 minutes. As the video catches up to where the class stopped reading, the teacher distributes a worksheet with a series of questions for the students to answer, like those shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Romeo and Juliet Worksheet

So many things in this example are problematic. First, we know that round-robin, cold reading aloud is not effective (Optiz & Rasinski, 1998). Some have even called it educational malpractice (Fisher, Lapp, & Flood, 2005). Once a student has read an assigned section, what is the motivation to pay attention? After all, what are the chances that a student will be called on twice during the same period? If students detect a pattern in terms of who is called upon to read, they will likely read ahead and practice their part and not pay attention to what is being read aloud. And can you blame them? All they want to do is sound good in front of their peers. Unfortunately, this comes at the expense of comprehension. When poorer readers are selected to read aloud, the entire class has to listen to choppy reading that does not help improve anyone's fluency or comprehension. For the struggling reader, this experience is torturous. Students who find reading difficult will find any excuse to leave the classroom and hope that their absence is not noticed upon their return (see Mooney & Cole, 2000).

Second, we know that students think about texts according to the ways they are questioned about the text (Anderson & Biddle, 1975; Hansen, 1981). Students reading Romeo and Juliet in the way described in this scenario will likely focus on the details of the play and miss the major ideas. As they read—or listen, as the case may be—they will focus on minutia at the expense of thinking.

Third, the structure of the classroom did not provide for student engagement. Rather, students sat passively while listening to the text. Listening isn't the problem here. We know that read-alouds are a powerful way of engaging students (see Ivey, 2003). The problem is that the students didn't do anything with the text. Read-alouds need to be interactive. In their study of interactive read-alouds, Fisher, Flood, Lapp, and Frey (2004) identified seven factors for effective read-alouds, including:

- The read-aloud text was selected based on the interests and needs of the students as well as the content covered.

- The selection was reviewed and practiced by the teacher.

- A clear purpose for the read-aloud was established.

- The teacher modeled fluent reading.

- The teacher was animated and expressive during the read-aloud.

- Students discussed the text during and after the read-aloud.

- The read-aloud was connected to other reading and united events in the classroom.

Finally, and most important, this classroom did not provide students with opportunities to select books that were interesting and that they could read. "Getting through the content" is one goal, and the Romeo and Juliet unit of study based on a whole-class novel could be improved such that every student understood the plot, character development, setting, and other components of the story grammar. That still would not result in better readers and writers who read and write more—a goal that we believe must always complement the units of study in an English class.

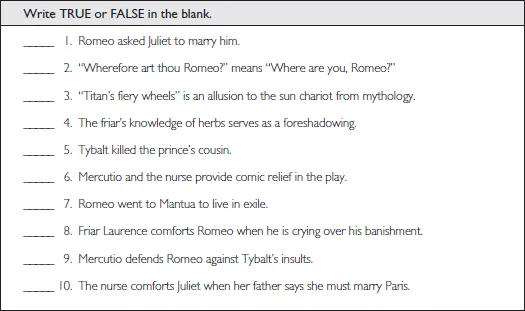

So what might be an alternative? A better way to organize this curriculum might be around a theme, a big idea, or an essential question (see Jorgensen, 1994–1995). Some examples of big ideas and essential questions appear in Figure 1.2 (see above). The teacher from the Romeo and Juliet scenario might have selected the idea "Love, Life, and Death" as a way to organize instruction. In doing so, he might have asked students to read different texts and to write about their personal experiences and interactions they had with the texts.

Figure 1.2. Examples of Big Ideas and Essential Questions

Although organizing instruction around a theme, a big idea, or an essential question might be an improvement, text selection plays an important—critical, in fact—role in what students will learn. Let's focus next on the texts that can, and should, be used in an English class that is well organized.

Text Difficulty

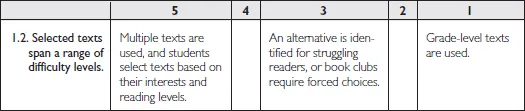

Area 1: English Language Arts Class

1. Are students' reading and writing development and relevant life experiences used to explore literary concepts?

Think about the English class that is organized around the idea of "Love, Life, and Death." It would not be much of a stretch to invite students to select one of the following books: West Side Story (Shulman, 1961) Romiette and Julio (Draper, 2001), or Romeo and Juliet Together (and Alive!) at Last (Avi, 1988). In this situation, students may be reading in small groups and discussing their books with groups of peers. These book clubs or literature circles add a level of engagement and discussion as students work in their groups (Daniels, 2002). Typically during these small-group discussions, students are assigned roles such as "discussion director" or "timekeeper." In addition, students may be assigned any of the following roles (Frey & Fisher, 2006, p. 133):

- Literary Luminary—chooses passages for discussion and formulates theories on their importance in the story.

- Connector—makes connections between events or characters in the book and personal experiences, other books, or events in the world.

- Illustrator—creates a sketch, graph, flow chart, or diagram to portray a topic for discussion.

- Summarizer—composes a statement that captures the main idea of the reading.

- Vocabulary Enricher—locates important words and provides a definition for the group.

- Researcher—investigates background information that is key to understanding the reading.

Although this approach is an improvement over the whole-class novel or another "grade-level" text, a teacher can do even more to engage students with texts. You probably noticed that the texts selected for discussion were all closely tied to Romeo and Juliet. As such, the choices were limited and the theme was constrained by someone's need to select texts that provided students with Romeo and Juliet in a lighter version. Some teachers who use this approach secretly pine away at the loss of Romeo and Juliet and hope that they will, some day, teach advanced placement or gifted students so that they can bring this classic back into the classroom.

If it sounds as though we hate Shakespeare, that isn't the case. Shakespeare and other works from the canon of great literature can and should be part of the English curriculum. We just know that texts have to be matched to students. We have a hard time imagining a 9th grade class of 36 students all reading, and willing to read, the same book at the same time.

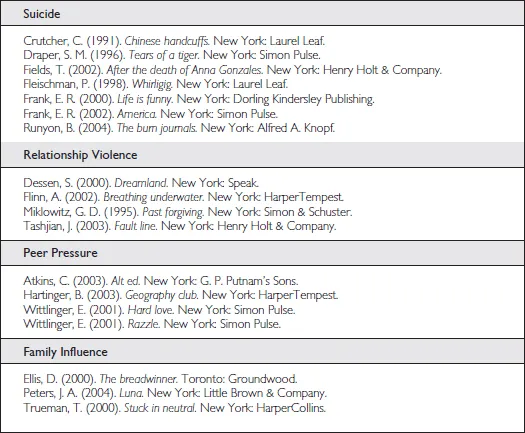

Returning to the big idea that guided the selection of these books, "Love, Life, and Death," we suggest expanding the selection of texts even further. Students thinking about the big idea may be concerned about issues of suicide, relationship violence, peer pressure, and family influence. Figure 1.3 contains a list of adolescent fiction that expands the exploration of the big idea into very different directions.

Figure 1.3. Books to Consider for the Big Idea of "Love, Life, and Death"

As you may have guessed, text selection is complex. There are so many good books to choose from and so little time! That's why we are concerned about selecting texts—time is limited, and it is wasted when students are not reading.

Not only do we want books that are aligned with a theme, a big idea, or an essential question, we also need books that students can read. Text difficulty is an important consideration in text selection. One factor to consider is the book's readability. Readability is fairly easy to determine, using one of two common methods: the Fry Readability Rating or the Flesch Reading Ease Score and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score.

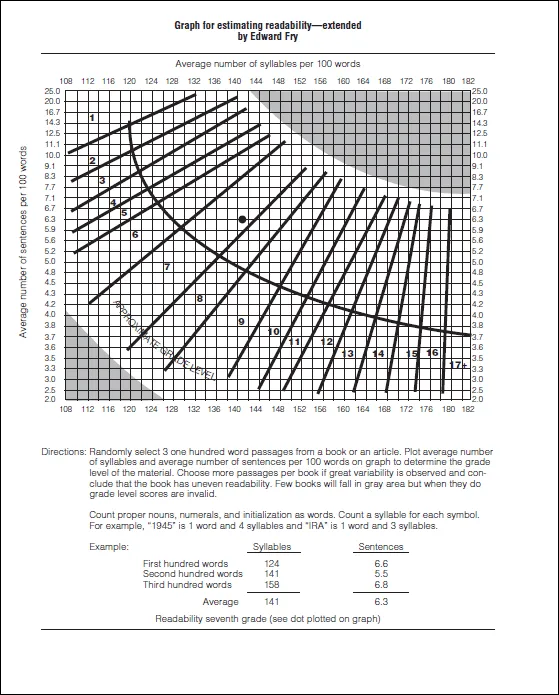

Fry Readability

A Fry Readability Rating can be calculated using the graph in Figure 1.4 and these simple steps:

- Select three 100-word passages from the book, preferably one each from the beginning, middle, and end.

- Count the number of sentences in each passage and the number of syllables in each passage.

- Average each of the two factors (number of sentences and number of syllables), then plot the result on the graph.

This will yield an approximate grade level.

Figure 1.4. Fry Readability Graph

Source: Fry, E. B. (1968, April). A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading, 11(7), 513–516. Reprinted with permission.

Flesch Reading Ease Score and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score

Most word-processing software programs have a feature for determining text difficulty. Simply type in a passage from a book you would like to assess, and then run the calculation. For example, the Microsoft Word program computes a Flesch Reading Ease Score on a 100-point scale. On this scale, the higher the score, the easier the text is to read. This software program also reports a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score to approximate difficulty.

To run these calculations on Microsoft Word, go to "Tools" on the toolbar and select "Spelling and Grammar." After running the spell check for the document, click on "Options" and check "Show readability formulas." After clicking OK, the program will report both scores. The Flesch Reading Ease Score for this section was a moderately difficult 56.1 and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score was 9.5.

Although readability formulas can be helpful, they cannot select books for students. In some cases, the content of the book is not consistent with the reading level at which the book was written. For example, a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level analysis of a section of Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut (1998), a satire of a world on the edge of an apocalypse, revealed a level score of 2.3. If you've read this book, you know it would hardly be appropriate for 2nd graders. Although this ex...