Engaging Minds in Science and Math Classrooms

The Surprising Power of Joy

- 65 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Engaging Minds in Science and Math Classrooms

The Surprising Power of Joy

About this book

"We decide, every day, whether we are going to turn students on or off to science and mathematics in our classrooms."

Daily decisions about how to incorporate creativity, choice, and autonomy—integral components of engagement—can build students' self-efficacy, keep them motivated, and strengthen their identities as scientists and mathematicians. In this book, Eric Brunsell and Michelle A. Fleming show you how to apply the joyful learning framework introduced in Engaging Minds in the Classroom to instruction in science and mathematics.

Acknowledging that many students—particularly girls and students of color—do not see themselves as mathematicians and scientists, the authors provide a series of suggested activities that are aligned with standards and high expectations to engage and motivate all learners. Given the current focus on encouraging students to pursue science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) studies, this book is a welcome addition to every teacher's reference collection.

Eric Brunsell is a former high school science teacher and is now associate professor of science education at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh.

Michelle A. Fleming is a former elementary and middle school teacher and is now assistant professor of science and mathematics education at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Understanding Joyful Learning in Science and Math

Defining Joyful Learning

A Joyful Learning Framework

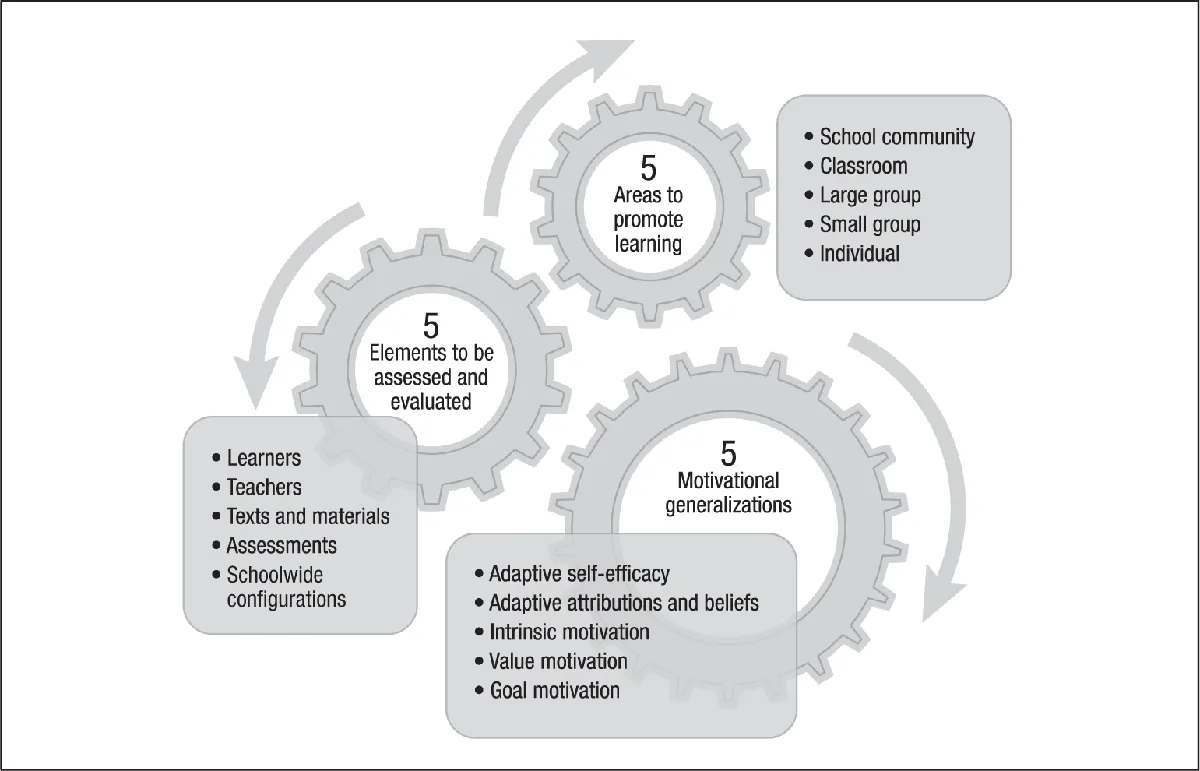

- Five motivational generalizations: adaptive self-efficacy and competence beliefs, adaptive attributions and beliefs about control, higher levels of interest and intrinsic motivation, higher levels of value, and goals.

- Five elements that need to be assessed and evaluated in order to get the most from joyful learning: learners, teachers, texts and materials, assessments, and schoolwide configurations.

- Five key areas in which to promote joyful learning: school community, physical environment, whole-group instruction, small-group instruction, and individual instruction.

FIGURE 1.1. Joyful Learning Framework

Motivation, Engagement, and Joy in Mathematics and Science

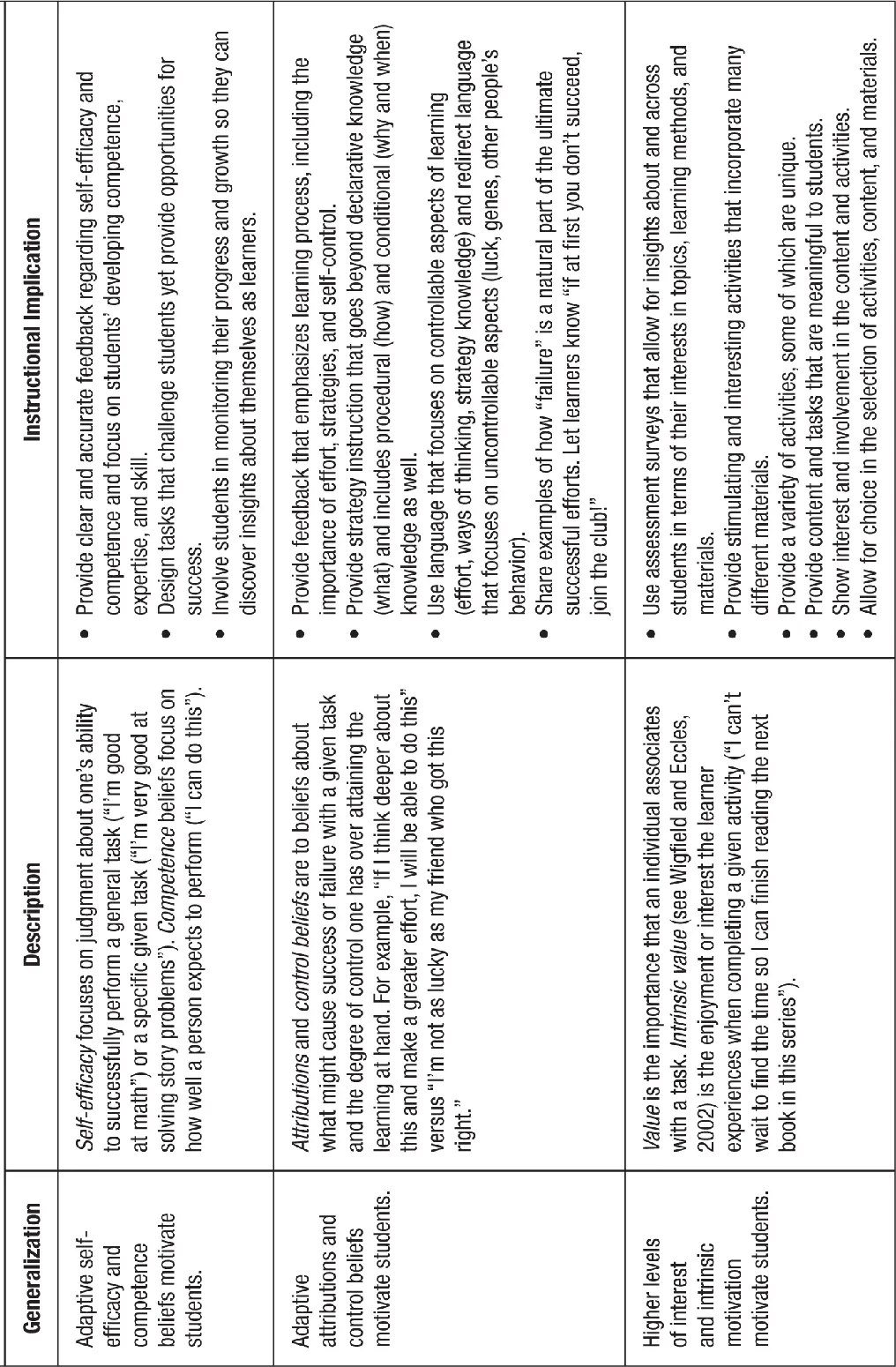

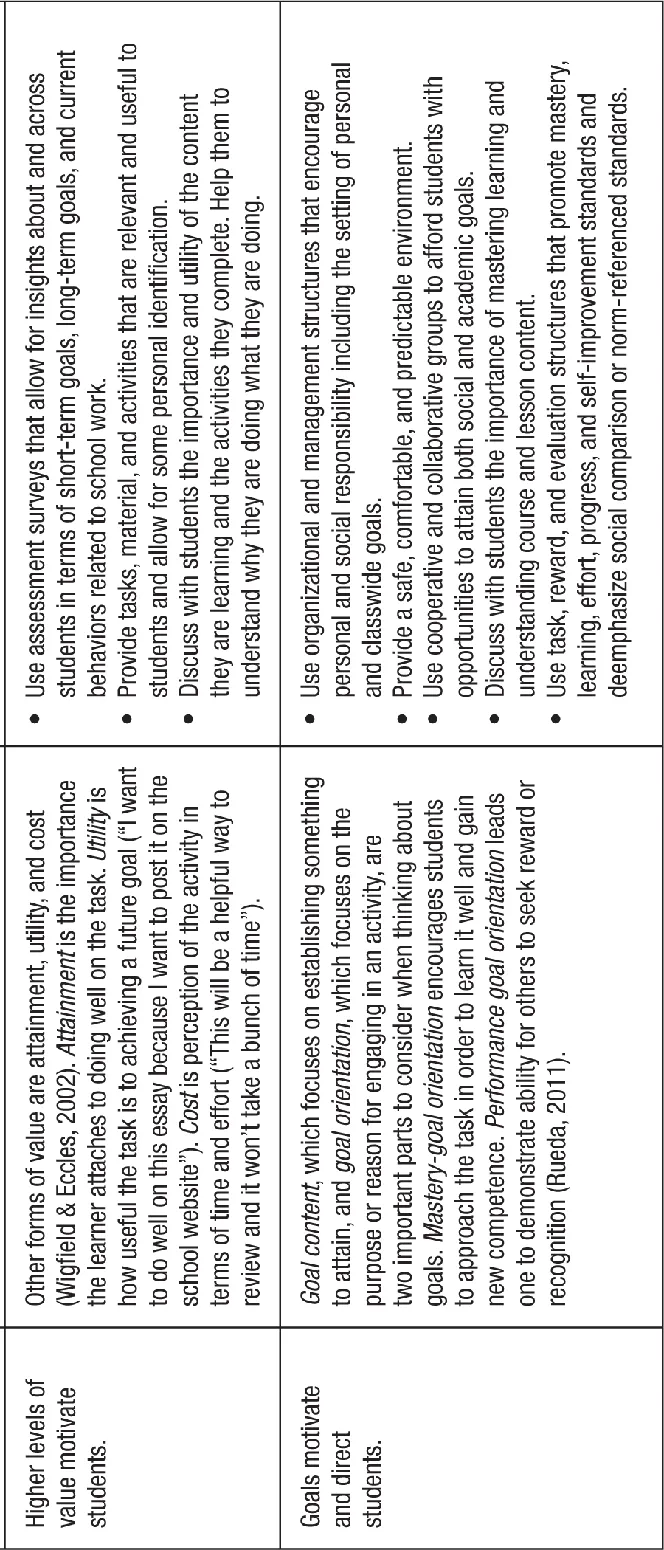

FIGURE 1.2. Generalizations About Motivation, and Instructional Implications

Students who perceived their classroom environments as more caring, challenging, and mastery-oriented classrooms had significantly higher levels of math self-efficacy than those in less caring, challenging, and mastery-oriented classrooms. In addition, we found that higher levels of math self-efficacy positively affected student math performance. (p. 736)

Implications for Teaching Science and Mathematics

Build on Student Interest

The day after his 8th grade science students learn that bacteria would not grow in small areas around certain spices, Alex Martinez engages them in a sense-making activity. He starts class with the prompt "Cultures in warmer climates tend to cook with more spices than those in cold climates. Researchers also found that meat dishes use more spices than vegetable dishes. Why do you think this is the case?" Students discuss this in small groups and then write arguments that include a claim and supporting evidence. Although they do not yet use the scientific vocabulary, Mr. Martinez's students in effect use evidence from the laboratory to explain the concept of a zone of inhibition.

Focus on Mastery Goals

Tanya Schaffer challenges her 6th grade students to apply their understanding of mathematics to an authentic task from the website Math by Design—and her lesson incorporates choice and autonomy. Students can work individually or in small groups. They can choose between the website's two projects: designing a community park or an environmental center. Because the tasks involved in the scenarios do not have obvious solution pathways, students also have to choose how to solve the tasks. At the conclusion, Ms. Schaffer's students respond to a series of questions that focus on the mathematical concepts underlying their decisions. With this project, Ms. Schaffer effectively promotes her students' mastery goals, keeping the emphasis on their learning and progress over getting a "correct" answer.

Establish Appropriate Level of Challenge

Sandra Kim has noticed that some students in her combined 2nd/3rd grade are struggling with the concept of regrouping during subtraction and addition problems and becoming frustrated. To allow students to use different representations of the problem and explore their own reasoning and that of their classmates, she introduces a "banking" activity. She gives some students (the "bankers") full sets of manipulatives consisting of multiple flats (equivalent to 100 blocks), rods (equivalent to 10 blocks), and individual blocks. The remaining students are paired up; one student from each pair has two rods and a flat (value: 120 blocks). Ms. Kim instructs these students to give their partners exactly 35 blocks. When they complain that it is not possible, she acts surprised: "But don't you have 120? Why can't you give your partner 35?"

She displays the problem (120 − 35) on an interactive whiteboard, which also includes images of base-10 blocks. The pairs of students work with bankers to make exchanges that will allow them to subtract the correct number of blocks; Ms. Kim shows the regrouping on the board, using both numbers and the virtual manipulatives. Afte...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Understanding Joyful Learning in Science and Math

- Chapter 2. Evaluating and Assessing Joyful Learning

- Chapter 3. Implementing Joyful Learning in Science and Math

- Chapter 4. Using Joyful Learning to Support Education Initiatives

- References

- About the Author

- About the Editors

- Related ASCD Resources

- Copyright