![]()

Chapter 1

Understanding Joyful Learning

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In the teachers' lounge, Mary and Mike are discussing their day when 5th grade teacher Kathy enters the room. "I planned a great social studies lesson. I pulled things off the web that I thought would spark discussion, but my kids sat there like rocks. What else can I do?"

"I seem to be the only one working in my classroom." says Mary, who teaches 6th grade. "I am trying to show how writing can be enjoyable, but I'm not succeeding. They only seem concerned about how many pages they need to write and the due date. The only enjoyment they seem to find in writing is getting finished."

"I've noticed the same thing," says Mike, a 4th grade teacher. "Many of my students hate math, and I am not really sure why or if I can convince them otherwise."

"What's so frustrating to me is that most of the students have the skills—they just don't seem to care much about applying them," Mary adds. "Maybe I'm sending mixed messages. Some days I am all about selling the love of learning. Other days I am preoccupied with getting them ready for the next round of tests. Maybe we need to take some time to explore ways to create some passion, to make learning more joyful."

"I think you might be onto something," Mike agrees.

Kathy nods, "I'm so busy trying to cover content that I haven't even thought about the joy."

"How about if we search out different ideas, try them out, and come back together to share?" Mary suggests. All agree that a collaborative plan aimed at helping students rediscover the joy of learning is worth pursuing and schedule their first meeting.

Teachers often grapple more with the challenges of the noncognitive, affective dimensions of learning and teaching than with the cognitive aspects. In fact, when we ask teachers what their number one concern is surrounding teaching and learning, they more often than not identify motivation and engagement. For many teachers, their greatest concern is how to engage their students. They know that if students want to learn, success is likely to follow.

When we delve deeper into why motivation and engagement are such a concern, three reasons surface. First, teachers believe (and rightly so) that education enables individuals to live more fulfilled lives. They talk at length about the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that will be required of students for them to lead fulfilling lives. Teachers know that supporting students to become lifelong learners (learning how to learn and wanting to continue to learn) will be crucial in a world in which they will need to be able to keep up with and embrace rapid changes. We only need to look at recent changes in technology for one example. In the words of one teacher, "We don't know what our students will be encountering in the future. So we need to help students see the value of learning and how it will contribute to their lives."

A second reason teachers focus on motivation is that they have experienced the pleasure associated with learning and they want to pass these feelings of pleasurable learning—a form of intrinsic motivation—along to their students. Like our own stories in the Introduction, and like the stories of writers who contributed to Sell's A Cup of Comfort for Teachers (2007), most teachers have stories about teachers who were powerful influences on their lives. Many became teachers to pass on those same feelings to their students. They wonder, how did their teachers motivate them? And can they as teachers emulate these practices so that their students can experience joyful learning?

Third, given the current focus on accountability—and particularly the linking of student performance to teacher salaries and their continued employment—teachers' job security may be affected by students' motivation to learn. The irony is that because teachers feel pressured to get students to perform on state tests, they are sometimes their own worst enemy when it comes to motivating students. For example, given the pressure to perform in a short amount of time, teachers may present material in a way that students perceive as boring and without meaning or purpose, and students are therefore not motivated to learn. As Cushman (2010) reported,

The most boring material students had in class, they told me, was often directly linked to high-stakes standardized tests they would be taking. Kids could tell that their teachers worried about tilting the balance toward fun activities at the expense of "rigorous" material that might be on the test. (p. 111)

Often education policy leads us away from addressing affective concerns such as developing a desire to learn content and an appreciation for what is being learned (Brophy, 2008). In the end, ignoring the affective development of our students leaves us further from accomplishing academic goals. Consider what has happened since the No Child Left Behind Act (2001) and its accompanying mandates. In our desk-bound "race to the top," recess is often cut and physical education, art, and music programs are scaled back, if they exist at all. In their place are more content classes perceived to be more rigorous and important to helping students pass high-stakes tests. As Willis (2007) noted, "In their zeal to raise test scores, too many policymakers wrongly assume that students who are laughing, interacting in groups, or being creative with art, music, or dance are not doing real academic work" (p. 1).

Yet there is compelling evidence that recess, PE, art, and music activities can help improve students' academic achievement. For example, students who get fitness-oriented classes in lieu of extra "academic" classes outperform those who take the extra classes to the exclusion of participating in fitness classes (Castelli, Hillman, Buck, & Erwin, 2007; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Medina, 2008; Ratey, 2008).

Other important evidence is found in the field of neuroscience. Neuroimaging and neurochemical researchers' findings suggest that enjoyable classroom experiences that capitalize on students' interests and relevance to their everyday lives heighten their learning (Chugani, 1998; Pawlak, Magarinos, Melchor, McEwen, & Strickland, 2003).

Finally, let's remember that many students find great joy in taking fitness and fine arts classes. For some students, these classes are the reason they show up at school each day and give them motivation to persevere in their other courses. Thus, eliminating such courses not only prevents some students from experiencing joyful learning but also thwarts students' academic growth.

Although we believe that focusing on the cognitive side of learning is important, there should still be room for thinking about learning as a pleasurable experience (i.e., the noncognitive side of learning) and how to create a context that will promote such pleasure. Like Olson (2009), we find this lack of focus on pleasurable learning (joyful learning) troubling because "pleasure in learning is one of the transcendent experiences of human life, one that offers meaning and a sense of connection in ways that few other activities can" (p. 30). But how can we attend to the pleasure that can be found in learning—or immerse our students in the joy of learning? Will attending to joy better ensure that students' learning of specific content has staying power? In this chapter we answer these important questions.

Defining Joyful Learning

We define joyful learning as acquiring knowledge or skills in ways that cause pleasure and happiness. Recently the focus has been on the first half of that definition (e.g., knowledge or skills) to the exclusion of the second half (e.g., pleasure and happiness). The joyful learning environment does not necessarily equate to an "anything goes" or a chaotic atmosphere. Instead, what we are suggesting is that wrestling with new ideas and taking risks to learn new content requires persistence and the willingness to work through difficulties as they arise; through this experience, students experience joyful learning. Joyful learning is in keeping with what Waterman (2005) called "high effort-liked activities." As Tough (2012) substantiated, learning takes grit—and joy emanates from the pursuit of attaining new learning as much or more so than attaining it. Tough's point echoes that of Rantala and Maatta (2012), whose ethnographic and observational research led them to conclude that engaging in the activity is what produced students' pleasure and joy.

A Joyful Learning Framework

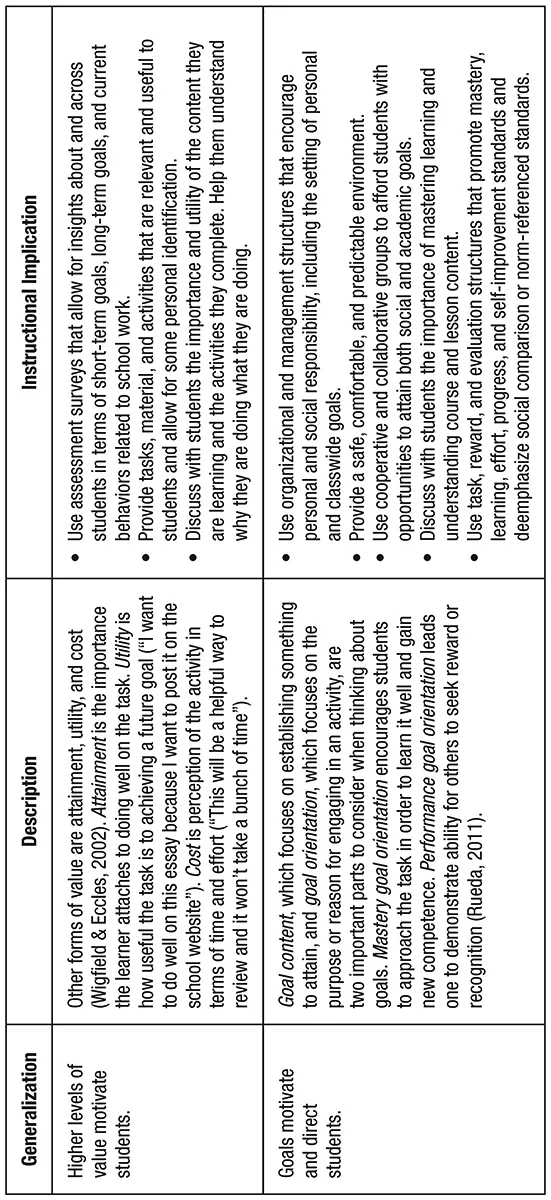

Our review of the research and reflection on our own experiences have helped us see that joy has everything to do with learning. What also became clear to us is that understanding why joyful learning is so important left questions about how to implement it unanswered. We saw the need to create a framework that would help teachers make decisions about joyful learning more systematic, intentional, and purposeful. Our framework consists of three parts.

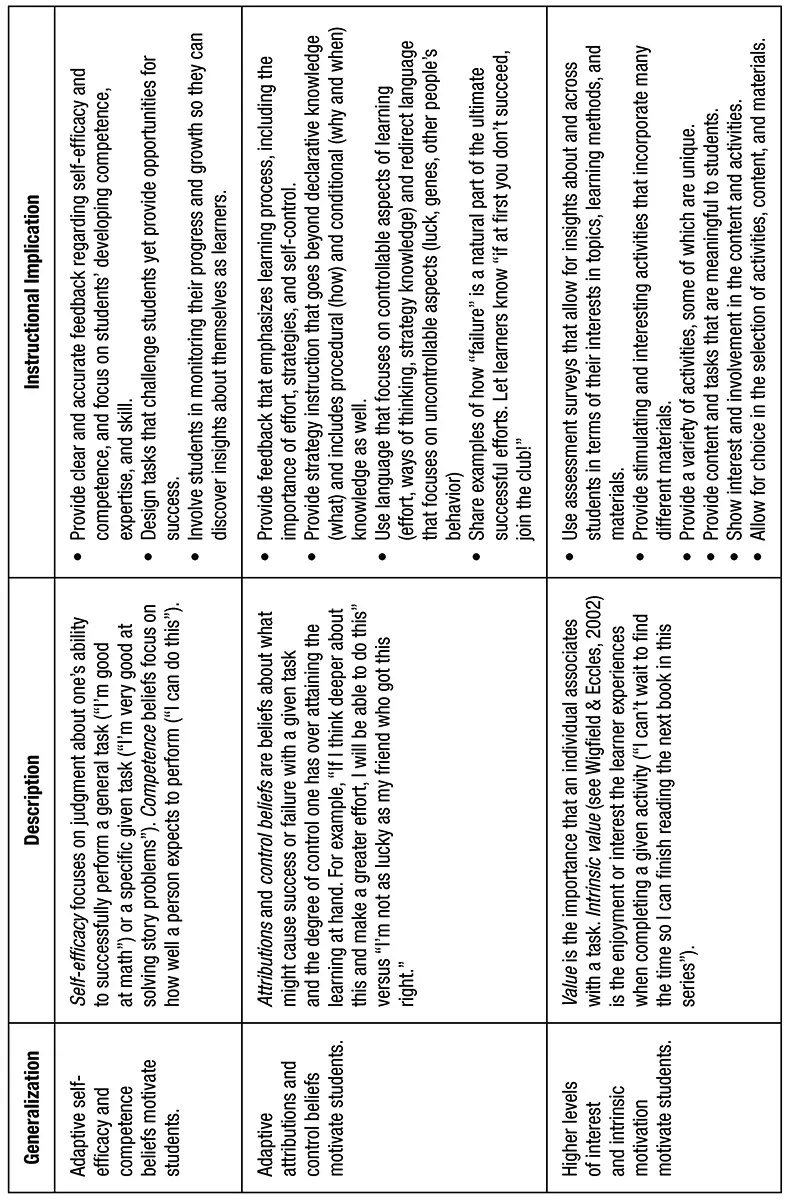

- Five motivational generalizations: adaptive self-efficacy and competence beliefs, adaptive attributions and beliefs about control, higher levels of interest and intrinsic motivation, higher levels of value, and goals. These generalizations are shown in Figure 1.1.

- Five elements that need to be assessed and evaluated in order to get the most from joyful learning: learners, teachers, texts and materials, assessments, and schoolwide configurations.

- Five key areas to promote joyful learning: school community, physical environment, whole-group instruction, small-group instruction, and individual instruction.

FIGURE 1.1 Generalizations About Motivation, and Instructional Implications

Generalizations adapted from Pintrich, 2003.

As a practical extension of joyful learning, we have also identified teaching activities in each of the five areas that are compatible with what we learned. We offer those activities (in Chapter 3) so that you can see how the framework comes to life in a classroom. The full framework for joyful learning appears in Figure 1.2 and is the basis for planning and teaching and learning using our research and experience.

FIGURE 1.2 Joyful Learning Framework

Setting Up Joyful Learning Experiences

Pleasure and joy are synonymous and truly can be found in learning environments. Olson (2009) noted that there are three kinds of pleasure that prompt learning: autonomous pleasure, social reward, and tension and release. Although often overlooked, autonomous pleasure has a sizeable effect on attitude and performance; we can't overemphasize the role that choice plays in joyful learning. When summarizing research related to autonomy, Pink (2009) concluded, "Autonomy promotes greater conceptual understanding, better grades, enhanced persistence at school and in sports activities, higher productivity, less burnout, and greater levels of psychological well-being" (p. 89). The three pleasures (autonomous, social reward, and tension and release) together suggest that joyful learning encompasses motivation and engagement. Here we'll discuss what motivation and engagement mean to teachers seeking to establish a joyful learning environment.

Motivation

Finding ways to motivate children is not difficult. But motivating them to learn sets up an additional challenge, and motivating students to learn in school complicates that challenge. As Pressley (2006) pointed out

Academic motivation is a fragile commodity…. For academic motivation to remain high, students must be successful and perceive that they are successful…. The policies of most elementary schools are such that most students will experience declining motivation, perceiving that they are not doing well, at least compared to other students. (p. 372)

The good news is the wealth of research about what motivates students to learn in classrooms. As Pressley stated, "much is being learned about how to reengineer schools so that high academic motivation is maintained" (2006, p. 372). Most relevant to our discussion is that researchers (e.g., Ames, 1992; Bandura, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Dweck, 2009; Locke & Latham, 2002; Wigfield & Eccles, 2002) have created many different social-cognitive models and constructs in an effort to answer and explain how to best motivate students. According to Pintrich (2003), regardless of the model or construct, all can be classified into one of five motivational generalizations, each of which has instructional implications (refer to Figure 1.1).

Teachers who understand and use motivation principles may be better equipped to discover ways to construct joyful learning experiences. But as Pintrich (2003) cautioned, when considering how to best capitalize on these motivation principles to create joyful learning experiences, there is no one-size-fits-all model. Rather, paying attention to what motivates their particular students will lead teachers to design motivational classrooms including activities that students perceive to be fun as a way to motivate them and spark their learning.

Many different combinations of motivation principles are viable. As Dolezal, Welsh, Pressley, and Vincent (2003) discovered, teachers who highly engage their students use many different motivating practices, including...