![]()

Chapter 1

Deepening the Concept

In 1998, teacher Jennifer Fielding was attracted by the energy and innovations at Belvedere Middle School, across town from where she worked. That fall she asked for and received an in-district transfer to the school. As soon as she arrived, however, she was disappointed: the principal had left, preliminary reforms had failed to materialize, and naysayers had gained new prominence. It looked as though the school would soon revert to its old ways.

The new principal, John Trevor, and a few strong teacher leaders responded wisely. After careful thought and assessment, Principal Trevor saw that his challenge was to reaffirm and build on the reforms that had begun, break through the barriers inhibiting further progress and change, and assure staff that he would remain until plans were well implemented. Rather than reclaim the authority that had been shared, he would work as a peer to move the school to the next level of development.

By the early spring of 1999 Belvedere was on strong footing again, having weathered lost momentum and flagging spirits. The school possessed many of the features of high leadership capacity: broad-based, skillful participation; a shared vision; established norms of inquiry and collaboration; reflective practice; and improving student achievement. Jennifer became a rapt student of leadership, working closely with the principal and teacher and parent leaders. By the fall of 2000, she had entered the leadership preparation program at her local university.

In the summer of 2001, Principal Trevor decided to accept an assistant superintendency in a nearby district. The superintendent of Belvedere's district called Jennifer and asked her to pay him a visit; he wanted to see if she was interested in applying for the principalship. As honored as she was apprehensive, Jennifer listened as the superintendent asked her three questions:

- What have you learned about leadership?

- What have you learned about leadership capacity?

- Can you help sustain Belvedere's high leadership capacity?

What Is Leadership?

What had Jennifer learned about leadership?

"Leadership," she told the superintendent, "is about learning together toward a shared purpose or aim."

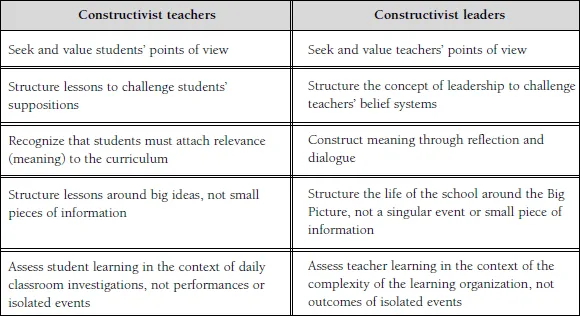

Learning and leading are deeply intertwined, and we need to regard each other as worthy of attention, caring, and involvement if we are to learn together. Indeed, leadership can be understood as reciprocal, purposeful learning in a community. Reciprocity helps us build relationships of mutual regard, thereby enabling us to become colearners. And as colearners we are also coteachers, engaging each other through our teaching and learning approaches. Adults as well as children learn through the processes of inquiry, participation, meaning and knowledge construction, and reflection (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1. A Comparison of Constructivist Teaching and Leading

Note: Adapted from a paper by Janice O'Neil at the University of Calgary.

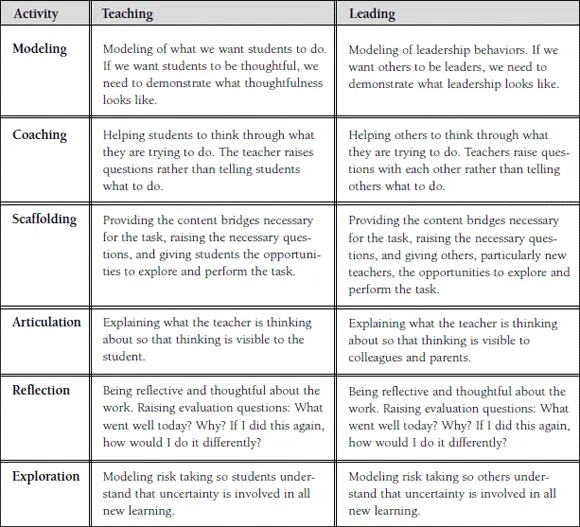

Figure 1.2. Parallels Between Teaching Habits of Mind and Leading

Note: Adapted from Costa and Kallick (2000) and Lambert et al. (2002).

Figure 1.1 suggests ways of applying constructivist principles for teaching to the realm of leadership. As leaders, we must bear in mind the learners' views, challenge their beliefs, engage them in assessments that take into account the complexities of the broader context (e.g., leading beyond the classroom), and construct meaning and knowledge through reflection and dialogue. Figure 1.2 draws parallels between teaching "habits of mind" (Costa & Kallick, 2000) and leading. These parallels suggest that leadership is the cumulative process of learning through which we achieve the purposes of the school.

As principals and teachers, we must attend not only to our students' learning but also to our own and to that of the adults around us. When we do this, we are on the road to achieving collective responsibility for the school and becoming a community of learners.

How we define leadership frames how people will participate in it. For instance, if we think of acts of leadership as "doing what the community needs when it needs to be done," they could include such simple tasks as inviting a new teacher to a meeting, raising a question that challenges established beliefs, or taking notes in an action research group.

Within the context of education, the term "community" has almost come to mean any gathering of people in a social setting. But real communities ask more of us than merely to gather together; they also assume a focus on a shared purpose, mutual regard and caring, and an insistence on integrity and truthfulness. To elevate our work in schools to the level required by a true community, then, we must direct our energies and attention toward something greater than ourselves.

When we learn together as a community toward a shared purpose, we are creating an environment in which we feel congruence and worth. Inherent to this view is the belief that all humans are capable of leadership, which complements our conviction that all children can learn. This vision of leadership asks that we keep in mind the following assumptions:

- Everyone has the right, responsibility, and capability to be a leader

- The adult learning environment in the school and district is the most critical factor in evoking acts of leadership

- Within the adult learning environment, opportunities for skillful participation top the list of priorities

- How we define leadership frames how people will participate in it

- Educators yearn to be purposeful, professional human beings, and leadership is an essential aspect of a professional life

- Educators are purposeful, and leadership realizes purpose

These assumptions determine our understanding of the work of leadership, which is integral to the definition of leadership capacity.

What Are We Learning About Leadership Capacity?

By "leadership capacity" I mean broad-based, skillful participation in the work of leadership. By "broad-based" I mean that if the principal, a vast majority of the teachers, and large numbers of parents and students are all involved in the work of leadership, then the school will most likely have a high leadership capacity that achieves high student performance.

But breadth of participation alone does not result in high leadership capacity; skillful involvement is needed as well. Otherwise our work together is unfocused, unproductive, and chaotic. Collaboration without skill is unsatisfying and will inevitably be abandoned for unilateral and thus more efficient ways of working. Collaboration that doesn't work can be a real setback, because it makes participants more hesitant to offer their time and commitment to working with others in the future. (I discuss the skills necessary for successful collaboration more fully in Chapter 3.)

Leadership capacity can refer to an organization's capacity to lead itself and to sustain that effort when key individuals leave; to the specific individuals involved; and to role groups, such as principals, teachers, parents and community members, and students. For the purposes of this book, however, I have focused my discussion primarily on leadership capacity as an organizational concept.

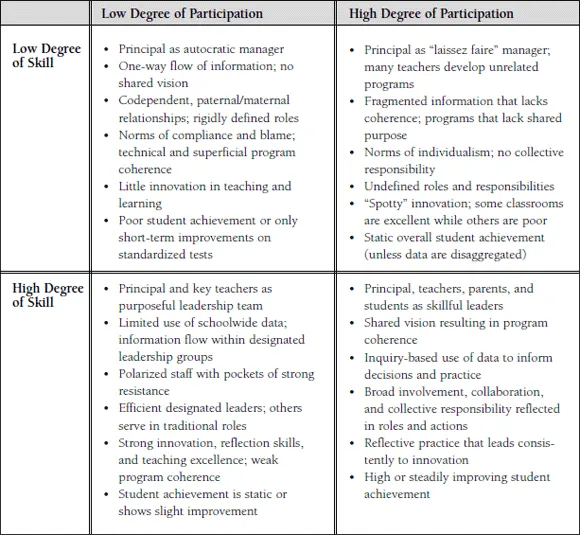

The combination of breadth of participation and depth of skillfulness gives rise to four possible organizational leadership capacity scenarios, as seen in Figure 1.3. Each quadrant in the figure includes a set of parallel features relating to the role of the principal, information and inquiry, program coherence, collaboration and responsibility, reflection, and student achievement. It is only when a school staff has undertaken skillful work using inquiry, dialogue, and reflection to achieve student performance goals that a school can be said to have achieved high leadership capacity (Quadrant 4).

Figure 1.3. Leadership Capacity Matrix

The Features of Leadership Capacity

The features of each quadrant in Figure 1.3 relate to critical aspects of school improvement. Research and experience tell us that the characteristics in Quadrant 4 are prerequisites for high leadership capacity schools and organizations (Newmann & Wehlage, 1995).1 I describe these criteria more fully in the chapters that follow, but below is a brief introduction to each.

Principals, Teachers, Parents, and Students as Skillful Leaders

Principals, teachers, parents, and students are the key players in the work of schooling. When working together, they form a concentration of leadership that is a powerful force in a school. If led by a skillful principal, teachers will often band together to form a team of professionals that invites parents and students into the work of leadership.

When individuals work together in reflective teams, they make the most out of their combination of talents. For instance, faculty meetings are occasions for educators to learn collaboratively, action research teams elicit inquisitiveness and a regard for evidence, and study groups test the assumptions of their members by introducing them to new ideas.

Shared Vision Resulting in Program Coherence

A principal's vision, standing alone, needs to be "sold" and "bought into." By contrast, a shared vision based upon the core values of participants and their hopes for the school ensures commitment to its realization. Realizing a shared purpose or vision is an energizing experience for participants, and a shared vision is the unifying force for participants working collaboratively.

Commitment to a shared vision provides coherence to programs and learning practices. Without coherence, wonderful classrooms operate next door to poor ones, and pioneering instructional practices under the same roof as ones that were long ago discredited. Every principal knows that parents will demand that their children be placed in the best classrooms with the best teachers. And who can blame them? We all want the best for our children. When quality stretches across the school's classrooms, curriculum, assessment, and instruction, we can provide equitable learning experiences for all children.

Inquiry-Based Use of Information to Inform Decisions and Practice

In a school that meets the criteria outlined in Quadrant 1 of the Leadership Capacity Matrix, information travels in a single direction—from the top to the bottom—without engaging in dialogue or negotiating new ways of thinking. A school that meets the criteria of Quadrant 4, however, provides a generative approach to discovering information and making collaborative, inquiry-based decisions. Questions are posed, evidence is collected and reflected upon, and decisions and actions are shaped around the collected findings. Outside information and formal research are mediated by the inquiry process. School community members understand that they are the primary leaders of the improvement process.

Information gleaned through inquiry informs both decisions and practice. Teachers frustrated by unruly students, bullying in the halls, or disrespectful classroom behavior, for example, will typically express their feelings in a faculty meeting. If the norm is to jump from the expression of opinions to action, then the faculty might simply decide to adopt a stricter discipline code. But if opinions lead to inquiry before action, a consideration of multiple voices, such as those of parents and students, might lead to efforts at building community in the classroom, mentoring students, or expanding student involvement in the school in addition to an examination of discipline codes.

Broad Involvement, Collaboration, and Collective Responsibility Reflected in Roles and Actions

As individuals work together, their personal identities begin to change: principals expect colleagues to participate more fully, teachers find more efficient ways to do their work, and parents and students shift from seeing themselves as subjects to seeing themselves as partners. Collaboration and the expansion of roles lead to a sense of collective responsibility for all the students in the school, the broader school community, and the education profession as a whole. The more people who work collaboratively are able to experience their profession outside the school—through networks, conferences, professional organizations, etc.—the broader their scope of responsibility becomes. As a kindergarten teacher recently told me, "When I began this work as a teacher leader, I saw myself as a kindergarten teacher. Now I see myself as an educator." What she meant was that she was now ready, "as an educator," to assume responsibility for schoolwide improvements—and in her case specifically, for novice teachers and a university partnership.

Reflective Practice that Leads Consistently to Innovation

Reflective practice—that is, thinking about your own practice and enabling others to think about theirs—can be a source of critical information or "data." Practice here means how we do what we do—methods, techniques, strategies, procedures, and the like. Parents practice parenting; students practice learning and contributing to others; and teachers practice teaching, learning, and leading. Reflection enables us to reconsider how we do things, which of course can lead to new and better approaches to our work.

Strategies for reflection include writing about practice (in journals or otherwise), peer coaching, debriefing (of meetings, lessons, etc.), studying articles or books with peers, and reflecting on the results of student interviews. Reflection is our way of making sense of the world around us through metacognition.

High or Steadily Improving Student Achievement

"Student achievement" in the context of leadership capacity is much broader than test scores. Measures of student achievement include multiple measures of development and performance, which in addition to test scores includes portfolios, exhibits, self-knowledge, and social maturity. This broad or comprehensive understanding of student achievement includes personal and civic development such as is involved in the work of "resiliency." Developmental factors of resiliency include: social bonding, opportunities to participate and contribute to others, problem-solving and goal-setting skills, and a sense of being in charge of one's future. Further achievement concerns are related to closing the yawning gap in achievement—typically derived from statistical measures such as test scores—among students of different genders, ethnicities, and socioeconomic statuses. At the heart of this problem are the differential skills and knowledge with which students enter and leave school. As a result, the average black or Latino student graduates from high school with the same skill set in math, reading, and vocabulary as a white 8th grader (Hammond, 1999). Each of these student-learning factors—academic performance, resiliency, and equitable outcomes for all students—is at the heart of leadership capacity; indeed, it is the compelling content of leadership.

Leadership Capacity Scenarios

The above features of leadership capacity are combined in each quadrant of Figure 1.3 to form a school "type." A caution: categories, types, and boxes are metaphors for our tendency to exist in a particular way. No school will or should "fit" exclusively into one quadrant. However, one can expect to find that a school has a tendency to function more in one way than another, signaled by a set of features that cluster together. This tendency to function at a particular level of leadership capacity is a changing, dynamic process.

The Quadrant 1 School

Jennifer became dissatisfied with her original school, Creekside, when she realized that neither she nor her colleagues would be able to play a substantial role in achieving the mission of the school. Her efforts to become sufficiently well informed to make decisions about practice were thwarted by the school's top-down, one-way approach to disseminating information. Teachers were not expected to respond to the information they received—they would simply seek and either receive or be denied permission from the principal for most actions. Many teachers liked this "per...