![]()

Introduction to Data-Driven Educational Decision Making

Teachers have been using data about students to inform their instructional decision making since the early movement to formalize education in the United States. Good teachers tend to use numerous types of data and gather them from a wide variety of sources. Historically speaking, however, teachers have typically not incorporated data resulting from the administration of standardized tests (Mertler & Zachel, 2006).

In recent years—beginning with the adequate yearly progress requirements of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and continuing with Race to the Top (RTTT) and the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) assessments—using standardized test data has become an accountability requirement. With each passing year, there seems to be an increasing level of accountability placed on school districts, administrators, and teachers. Compliance with the requirements inherent in NCLB, RTTT, and the CCSS has become a focal point for schools and districts. For example, most states now annually rate or “grade” the effectiveness of their respective school districts on numerous (approximately 25–35) performance indicators, the vast majority of which are based on student performance on standardized tests.

As a result, the notion of data-driven decision making has steadily gained credence, and it has become crucial for classroom teachers and building-level administrators to understand how to make data-driven educational decisions.

Data-driven educational decision making refers to the process by which educators examine assessment data to identify student strengths and deficiencies and apply those findings to their practice. This process of critically examining curriculum and instructional practices relative to students’ actual performance on standardized tests and other assessments yields data that help teachers make more accurately informed instructional decisions (Mertler, 2007; Mertler & Zachel, 2006). Local assessments—including summative assessments (classroom tests and quizzes, performance-based assessments, portfolios) and formative assessments (homework, teacher observations, student responses and reflections)—are also legitimate and viable sources of student data for this process.

The “Old Tools” Versus the “New Tools”

The concept of using assessment information to make decisions about instructional practices and intervention strategies is nothing new; educators have been doing it forever. It is an integral part of being an effective educational professional. In the past, however, the sources of that assessment information were different; instructional decisions were more often based on what I refer to as the “old tools” of the professional educator: intuition, teaching philosophy, and personal experience. These are all valid sources of information and, taken together, constitute a sort of holistic “gut instinct” that has long helped guide educators’ instruction. This gut instinct should not be ignored. However, it shouldn’t be teachers’ only compass when it comes to instructional decision making.

The problem with relying solely on the old tools as the basis for instructional decision making is that they do not add up to a systematic process (Mertler, 2009). For example, as educators, we often like to try out different instructional approaches and see what works. Sounds simple enough, but the trial-and-error process of choosing a strategy, applying it in the classroom, and judging how well it worked is different for every teacher. How do we decide which strategy to try, and how do we know whether it “worked”? The process is not very efficient or consistent and can lead to ambiguous results (and sometimes a good deal of frustration).

Trial and error does have a place in the classroom: through our various efforts and mistakes, we learn what not to do, what did not work. Even when our great-looking ideas fail in practice, we have not failed. In fact, this process is beneficial to the teaching and learning process. There is nothing wrong with trying out new ideas in the classroom. It’s just that this cannot be our only way to develop strong instructional strategies.

I firmly believe that teaching can be an art form: there are some skills that just cannot be taught. I am sure that if you think back to your own education, you can recall a teacher who just “got” you. When you walked out of that teacher’s classroom, you felt inspired. Conversely, we’ve all had teachers who were on the opposite end of that “effectiveness spectrum”—who just did not get it, who were not artists in their classrooms. Even young students are able to sense that.

The concept of teaching as an art form is an important and integral part of the educational process, and I don’t intend to diminish it. Rather, what I want to do is expand on it by integrating some additional ideas and strategies that build on this notion of good classroom teaching. The old tools do not seem to be enough anymore (LaFee, 2002); we must balance them with the “new tools” of the professional educator. These new tools, which consist mainly of standardized test and other assessment results, provide an additional source of information upon which teachers can base curricular and instructional decisions. This data-driven component facilitates a more scientific and systematic approach to the decision-making process. If we think of the old tools as the “art” of teaching, then the new tools are the “science” of teaching.

I do not think that the art of teaching and the science of teaching are mutually exclusive. Ideally, educators would practice both. In this publication, however, I focus on the data-driven science of teaching.

A Systematic Approach

Taking the data-driven approach to instructional decision making requires us to consider alternative instructional and assessment strategies in a systematic way. When we teach our students the scientific method, they learn to generate ideas, develop hypotheses, design a scientific investigation, collect data, analyze those data, draw conclusions, and then start the cycle all over again by developing new hypotheses. Likewise, educational practitioners can use the scientific method to explore and weigh our own options related to teaching and learning. This process is still trial and error, but the “trial” piece becomes a lot more systematic and incorporates a good deal of professional reflection (Mertler, 2009). And, like the scientific method, the decision-making process I describe in the following sections is cyclical: the data teachers gather through the process are continually used to inform subsequent instruction. The process doesn’t just end with the teacher either deciding the strategy is a winner or shrugging and moving on to a new strategy that he or she hopes will work better.

A major reason teachers don’t rely more on assessment data to make instructional decisions is the sheer volume of information provided on standardized test reports. One teacher comment I often hear is, “There is so much information here that I don’t even know where to start!” One way to make the process less overwhelming is to focus your attention on a few key pieces of information from test reports and other assessment results and essentially ignore other data, which are often duplicative.

Another anecdotal comment I often hear from teachers provides a reason why many educators resist relying on assessment data—that is, the belief that using test results to guide classroom decision making reduces the educational process to a businesslike transaction. It’s true that in business settings, data are absolutely essential. Information about customers, inventory, and sales, for example, are crucial in determining a business’s success or failure. In contrast, in education we tend to focus more on the “human” side of things. Rightfully so, of course: kids are living, breathing entities, whereas data are abstract. For many educators, this truly makes data a four-letter word (LaFee, 2002). Yet we don’t need to view data as antithetical to the educational process; there’s room for the data side and the human side.

The idea of data-driven decision making is not new, but incorporating data into instruction does take some practice on the part of the classroom teacher. The following section should shed some light on this practice and help make it a less intimidating process.

Understanding How to Look at the Data: Advice and Caveats

Educators can effectively use student assessment data to guide the development of either individualized intervention strategies or large-group instructional revisions. Regardless of the purpose and goals of the decision-making process, it is important to heed some cautionary advice before examining the results of standardized tests.

Generally speaking, standardized achievement tests are intended to survey basic knowledge or skills across a broad domain of content (Chase, 1999). A standardized test may contain as many as seven or eight subtests in subjects such as mathematics, reading, science, and social studies. Each subtest is then further broken down to assess specific skills or knowledge within its content area. For example, the reading subtest may include subsections for vocabulary, reading comprehension, synonyms, antonyms, word analogies, and word origins. One of these particular subsections may contain only five or six actual test items. Therefore, it is essential to interpret student performance on any given subtest or subsection with a great deal of care.

Specifically, educators must be aware of the potential for careless errors or lucky guesses to skew a student’s score in a particular area, especially if the scores are reported as percentile ranks or if the number of items answered correctly is used to classify student performance according to such labels as “below average,” “average,” and “above average.” This caveat also applies to local classroom assessments, including larger unit tests, final exams, or comprehensive projects. Whatever the type of assessment, it is important to avoid over-interpretation—that is, making sweeping, important decisions about students or instruction on the basis of limited sets of data (Russell & Airasian, 2012). Although over-interpreting results does not guarantee erroneous decision making, it is certainly more likely to result in flawed, inaccurate, or less-valid instructional decisions.

Prior to making any significant instructional or curricular decisions, it is therefore crucial to examine not only the raw scores, percentile ranks, and the like but also the total number of items on a given test, subtest, or subsection (Mertler, 2003, 2007). In addition, educators should consult and factor in multiple sources and types of student data to get a more complete view of student progress or achievement. These additional sources of data may be formal (e.g., chapter tests, class projects, or performance assessments) or informal (e.g., class discussions, homework assignments, or formative assessments). Looking at a broader array of data can help teachers avoid putting too much weight on a single measure of student performance and, therefore, reduce the risk of making inaccurate and invalid decisions about student learning and teaching effectiveness.

In the following sections, we will look at the two main ways classroom teachers can use student assessment results as part of the data-driven decision-making process: (1) developing specific intervention strategies for individual students, and (2) revising instruction for entire classes or courses (Mertler, 2002, 2003).

Decision Making for Individual Interventions

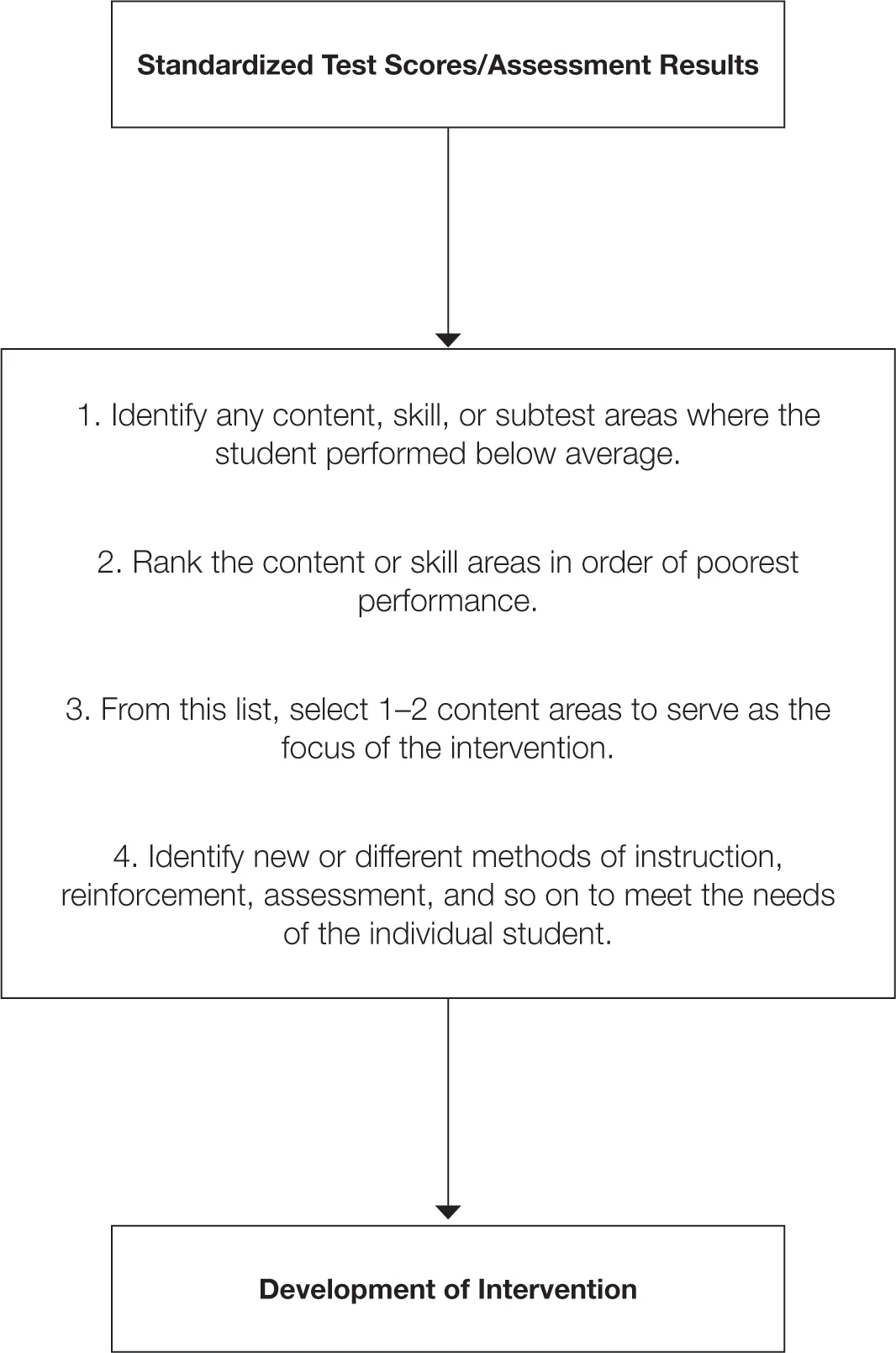

Figure 1 depicts the process for examining assessment results to make instructional decisions and develop intervention strategies for individual students (Mertler, 2007).

The steps shown in Figure 1 constitute a “universal” process for using standardized test data and other assessment results to guide intervention decisions. The process is universal in that it can be applied to any situation, regardless of grade level, subject area, type of instruction, or types of skills being taught. Seen separately, these steps are not

Figure 1: Universal Process for Identifying Areas for Individual Intervention

Standardized Test Scores/Assessment Results

↓

1. Identify any content, skill, or subtest areas where the student performed below average.

2. Rank the content or skill areas in order of poorest performance.

3. From this list, select 1–2 content areas to serve as the focus of the intervention.

4. Identify new or different methods of instruction, reinforcement, assessment, and so on to meet the needs of the individual student.

↓

Development of Intervention

particularly complex, but taken together they represent an ongoing, systematic process that enables educators to

- Take a large amount of assessment data.

- Narrow the focus for potential interventions on the subtests, content areas, or skills where student performance was weakest.

- Further pare down that list by focusing on the one or two most critical content or skill areas.

- Develop an intervention strategy for addressing the particular weakness(es) by identifying different modes of instruction, reinforcement or practice, or methods of assessing student learning and mastery.

Typically, a teacher might know which students in his or her class are struggling (by means of assessment performance or simple observations) but likely would not know the specific areas or skills where interventions should be targeted. The process begins with the teacher examining test reports or other obtained assessment results and identifying any content, skill, or subtest areas where a given student performed poorly or below average. If the teacher identifies more than one problem area, he or she should rank those areas in order of perceived severity of deficiency. The one or two highest-priority areas should then be selected as the focus of the intervention. Finally, the teacher should identify, develop, and implement new or different methods of instruction, reinforcement, or assessment to meet the needs of the individual student (Mertler, 2007).

An example of student-level decision making follows.

Example #1: Student-Level Decision Making

On the whole, Mrs. Garcia’s 1st grade class had been doing quite well in all tested areas of reading (phonemic awareness, alphabetic principle, vocabulary, and fluency and comprehension) on both the benchmark assessments and the monitoring assessments of the district-adopted standardized reading test. One student, however, was struggling with certain aspects of the assessments. Jacob seemed to be strong in phonemic awareness, having surpa...