- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

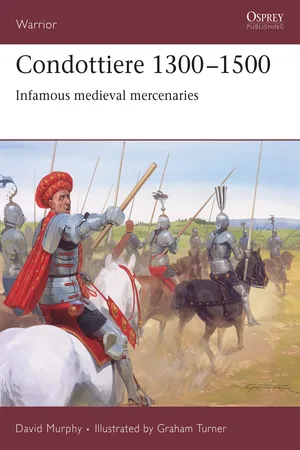

Originally contracted by wealthy Italian city states to protect their assets during a time of ceaseless warring, many condottieri of the Italian peninsula became famous for their wealth, venality and amorality during the 14th and 15th centuries. Some even came to rule cities themselves. Lavishly illustrated with contemporary depictions and original artwork, this title examines the complex military organization, recruitment, training and weaponry of the Condottieri. With insight into their origins and motivations, the author, Dr David Murphy, brings together the social, political and military history of these powerful and unscrupulous men who managed to influence Italian society and warfare for over two centuries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Condottiere 1300–1500 by David Murphy,Graham Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE CONDOTTIERE IN BATTLE

Organization, weaponry and tactics

During the period 1300–1500, the tactics of the condottieri developed to a great degree. A condottiere of the 14th century would most probably have been a non-Italian mercenary and would have used tactics perfected through use in the Hundred Years War. The subdivision into lances mentioned earlier could consist of four to five men and included a caporale (the leader), his squire and a page who accompanied the lance’s spare horses. These men could have further men-at-arms or archers attached to their lance.

The organization of condottieri companies varied from state to state. In Milan in the 1470s a four-man lance was the norm, while in the Papal States a five-man corazza was used. Five of these lances were grouped together to form a ‘post’, and five posts (25 lances) formed a squadron. A condottieri band (bandiera), often referred to as a condotte, numbered anywhere between 50 and 100 lances. There was room for contraction and expansion in this system of organization, and different condottieri bands, although technically the same type of unit, could vary greatly in size. This was especially true in the mid- to late 15th century, as the increasing weight of armour made more horses, and by extension more squires and pages, necessary in armies.

The age of the condottieri saw further developments in warfare. During the 15th century, light cavalry became increasingly important and were used to forage for food and, in combat, to scout and pursue a defeated enemy. By the 1470s the Italians began to recruit light cavalry known as stradiotti, who were usually of Greek or Albanian origin. The stradiotti had long served in Venetian armies but they began to be used by other Italian states. Armed with lances, bows or crossbows, they were the epitome of the light horseman. Around 1480 Naples began to employ Turkish light cavalry, who also proved to be excellent in this role.

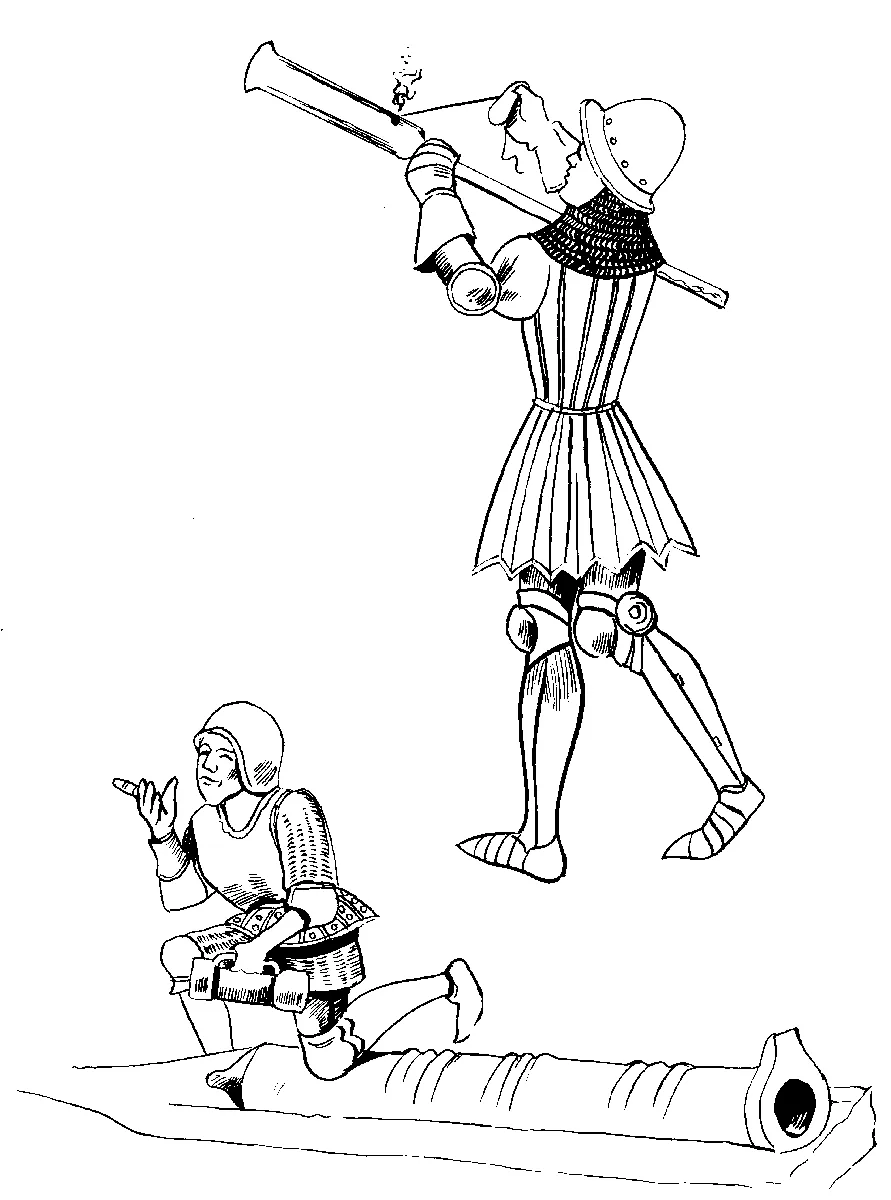

A contemporary illustration of a handgunner and artilleryman. Both wear helmets, leather jerkins and arm and leg protection. This combination provided good protection but left the gunners enough mobility to operate effectively. (Author’s collection)

Although condottieri warfare is usually associated with cavalry, the use of infantry also increased during the 15th century. These had previously been relegated to garrison duties as they were seen as being both vulnerable and unreliable in open actions. By the mid-15th century, condottieri armies were beginning to include large numbers of infantrymen. These were heavy infantry who wore relatively good armour protection and fought with sword or pole-arm. Condottieri armies also included light infantrymen who were armed with swords and buckler shields.

While some condottieri armies utilized archers, the primary Italian projectile weapon of the 14th and 15th centuries was the crossbow. Gradually, the improvement in gunpowder technology saw these replaced by handgunners. Handguns of this period were extremely basic and easy to produce and it was also relatively easy to train men in their use. The handgunner slowly supplanted the crossbowman in the armies of the 14th and 15th centuries and not only for garrison duties but also in the field armies.

The earliest Italian handgun, the schiopetto, dated from the late 13th century and in its simplest form was little more than a gun barrel with a vent hole mounted on a pole. Handgunners or schiopettieri formed a part of most armies but some states, such as Milan, began to give them increasing prominence in their army organization. In the War of Ferrara in 1482, for example, the Milanese army had over 1,200 handgunners and just 233 crossbowmen.

The technology of handguns had also improved, making them much more effective and reliable weapons. By the late 1400s, the arquebus had been developed: a full-stocked weapon with a spring-loaded trigger. The army of the Papal States in the 1490s was capable of fielding mounted arquebusiers.

A medieval artilleryman firing a bombard, which has been aligned like a modern mortar. He is well protected with helmet, mail shirt and quilted jerkin. Developments in handguns and artillery created new areas of specialism within medieval armies which would later leave the heavily armoured cavalryman redundant. (Author’s collection)

Larger gunpowder weapons proved more problematic. The technology of cannon-making advanced relatively slowly. In the field, the movement and deployment of cannon presented huge practical problems. Their slow rate of fire meant that they were often useful only for overawing less confident enemies. The usual practice was to use them in garrisons only. An increasing use of field fortifications in the 15th century meant that cannons found a new battlefield role. They were of most use in sieges and in 1357 Galeotto Malatesta was the first to use a bombard, a primitive type of mortar, in an Italian siege.

During the early 14th century the non-Italian condottieri introduced a new style of fighting. In battle the condottiere could engage his enemy on horseback using the accepted cavalry tactics of the period. However, he could also fight dismounted and two men of each lance would wield a heavy lance in a style that foreshadowed later pike tactics. This was an unusual but highly effective tactic in 14th-century Italy. A group of lances acting in this manner could come together in a large defensive hedgehog formation which opponents found difficult to break through. At the same time, if the condottieri were skilled enough they could advance in this formation in a style reminiscent of the Greek phalanxes. These tactics made condottieri companies a tough proposition on the battlefield.

The early condottieri also incorporated infantry in their companies. In the case of the English companies, these included longbowmen, who introduced a further dimension into 14th-century Italian warfare. In Italy, the crossbow was the more common projectile weapon and although its bolt could reach a greater range and had good penetrating power, its rate of fire was much slower than that of the longbow. The longbowmen of the English companies had proved at battles such as Crécy and Poitiers that they could unleash huge deadly showers of arrows on their enemies. This gave the English companies a brief window of tactical advantage during the 14th century. In the attack, they could use their longbowmen to drive back the enemy, or even the defenders away from the walls of fortifications. In defence, the longbow was unequalled in breaking up both cavalry and infantry attacks. While improvements in crossbows and hand-held firearms would soon negate this tactical advantage, the use of the longbow by English condottiere captains brought a new and dangerous dimension to Italian warfare. While some Italian military leaders such as Alberigo da Barbiano (d. 1409) thought that the use of infantry and the dismounting of cavalry denigrated the knightly elite, such tactics gave condottiere leaders increased advantages in terms of mobility on the battlefield.

Sforzeschi tactics

By the 15th century, two main schools of tactical thought had developed and these came to characterize condottieri battles. One of these tactical styles was developed by Muzio Attendolo (1369–1424). Born into a non-noble family in Cotignola in the Romagna region, Attendolo had served as a condottiere under Alberigo da Barbiano, himself a great condottiere and also a military theorist. It is generally accepted that Attendolo refined the tactics that he had learned as a squadron commander under Barbiano. During his career, Attendolo earned the nickname ‘Sforza’, which literally means ‘Force’. He and his descendants would be known by this name and in many ways it summarized the tactical ideas of Sforza and later followers of the ‘Sforzeschi’ school of thought.

A medieval clash of cavalry as depicted in Vanni’s fresco of the battle of Sinalunga. The more heavily armoured cavalrymen are followed by lightly armed horsemen, presumably representing light cavalry. Note also the heraldic devices and helmet plumes of the heavy cavalry and the padded armour of their horses. (Author’s photograph)

The Battle of Anghiari by an unknown Florentine master of the 1460s. This painting is in the style of the school of Uccello and depicts the clash between the condottieri army of Milan, commanded by Niccolò Piccinino, and a combined Florentine and Venetian army under the renowned condottiere Francesco Sforza. The battle, on 29 June 1440, lasted for over four hours and resulted in the defeat of the Milanese, establishing Florence as the dominant power in Tuscany. Due to the relatively small number of casualties, it was later ridiculed by Machiavelli as a bloodless condottieri battle. The Tiber is shown dividing the field of battle, while the towns in the background include Borgo Sansepolcro, Citterna and Monterchi. (National Gallery of Ireland, Cat. 778)

Like most great military leaders, Sforza inspired great loyalty from his men. He came to see this as essential to military success and through extensive training he instilled strict discipline in his condottieri. On campaign, he gathered all of his army together before a battle to ensure local superiority. He was cautious and planned each assault carefully. When he had met these self-imposed requirements, he unleashed his army in massed and carefully coordinated attacks. Unlike his mentor Barbiano, he had no reservations about using infantry and preferred to use combinations of cavalry and infantry assaults. Sforza’s philosophy was simple; if commanded correctly, his attack would fall upon his enemy with the force of a massive hammer blow.

Bracceschi tactics

The second school of tactical thought was developed by Braccio da Montone (1368–1424). Unlike Sforza, this Perugian was born into the lesser nobility but had become a condottiere to earn his living. He had also learned his profession under Barbiano and was, in his younger days, a comrade of Sforza. During his early career he had developed his own ideas on military tactics and these were a total contrast to those of Sforza and the later followers of the Sforzeschi school.

Braccio preferred to use a decisive tactical move to overwhelm his enemy and in that respect he was the master of the rapier cut rather than the hammer blow. He also inspired great loyalty among his men and trained them to a high degree. In battle his emphasis was on the tight control of his troops. He had a preference for using large cavalry formations and he committed each squadron of cavalry on a specific manoeuvre. Rather than merely unleashing his formations, he controlled them tightly, using them to find and exploit weak points in his enemies’ armies. He also developed the concept of a reserve and kept back formations, later introducing fresh troops into battle as his enemies became gradually exhausted.

Realities of combat

For an individual condottiere, these tactical considerations were probably quite irrelevant once battle was joined. From surviving paintings and accounts of the period it is quite obvious that condottieri battles were confused and brutal affairs, but there are also indications that discipline could be maintained among condottieri companies and that tactical plans were followed through.

The fight between the Bonacolsi and Gonzaga in the Piazza Sordello in Mantua, 1494. This painting by Domenico Morone is highly stylized and shows the clash between two Mantuan factions. The action is portrayed almost like a jousting session, yet close observation illustrates the brutality of close quarter fighting. (DeAgostini/Getty Images)

It was Italian practice to use a cart-like vehicle known as a carroccio as both command post and mobile fire platform. This was usually bedecked with the flags of the city or state that controlled the army. It appears that some condottieri leaders retained this system and controlled their armies from a carroccio or even from their personal tent. It was more common, however, for condottieri leaders to be present in the field, moving from one scene of action to another in order to control their men and react to enemy attacks. How they communicated their intentions once battle had been joined remains unclear, although one must assume that junior officers carried orders to sub-units during a battle. Illustrations of the period sometimes show condottieri leaders travelling with trumpeters and these would have had a battlefield signalling function.

How then did the condottieri perform in battle? Contemporary chroniclers and modern historians remain divided on this subject. Niccolò Machiavelli, author of the political treatise The Prince, dismissed their battles as bloodless jousts. He went on to sum up condottieri ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHRONOLOGY

- ENLISTMENT

- TRAINING

- DAILY LIFE

- APPEARANCE AND DRESS

- BELIEF AND BELONGING

- LIFE ON CAMPAIGN

- THE CONDOTTIERE IN BATTLE

- CONSPIRACY AND BETRAYAL

- AFTERMATH OF BATTLE

- CONCLUSION

- MUSEUMS, COLLECTIONS AND RE-ENACTMENT

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- COLOUR PLATE COMMENTARY

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

- eCopyright