![]()

1 The historic nation

To the Irish all History is Applied History, and the past is simply a convenient quarry which provides ammunition to use against enemies in the present. They have little interest in it for its own sake, so when we say that the Irish are too much influenced by the past, we really mean they are too much influenced by Irish History, which is a different matter. That is the History they learn at their mother’s knee, in schools, books and plays, on radio and television, in songs and ballads.

– Stewart, The Narrow Ground: The Roots of Conflict in Ulster, 16

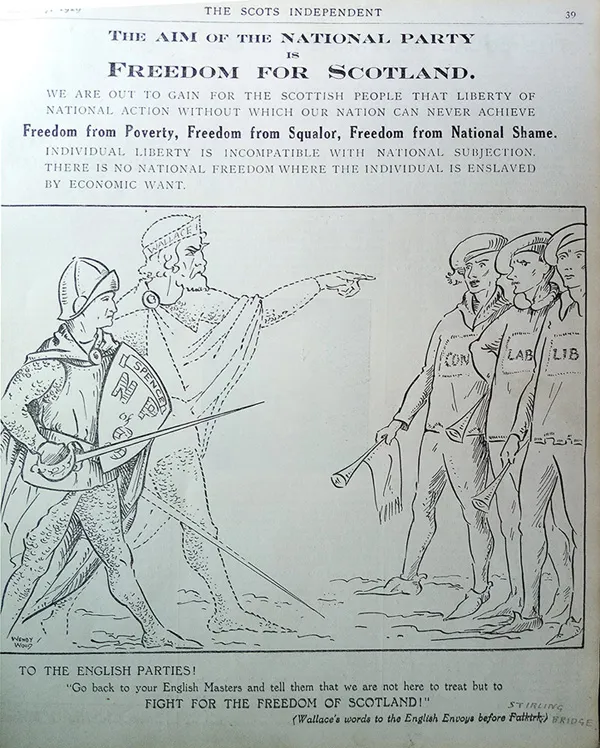

As Tony Stewart points out above, history can be, and often is, used to serve ideological purposes. All nationalist movements have used history as a political weapon to justify their aims and ambition because of its malleability to project and promote ideological objectives. The chapter starts off by looking at the relationship between history and nationalism and some of the peculiarities caused by the strange historical trajectory experienced by the Scottish nation which was independent up until the Union with England in 1707. So for most of its thousand odd years of history, Scotland was an independent national entity. The Union, however, meant that the Scottish historical experience was not that of a small nation that matured into statehood, such as the Netherlands, which was the historical trajectory that nationalists argued it should have had. Nor was it a history where the nation was absorbed by conquest by a larger and more powerful neighbour, such as Latvia or Ireland. Because of this it was difficult to construct a typical nationalist narrative of a quest for freedom from colonial oppression, although some did try. The Union of 1707 was a political settlement that absorbed much nationalist intellectual energy in explaining why a supposed freedom-loving nation, which had a proud record of rebuffing English endeavours at conquest, ended up surrendering its independence without a fight. All of which posed a real intellectual conundrum that was difficult to resolve. This chapter will explore the contradictions and complexities of why history has not provided the Scottish movement with the same ideological props enjoyed by other European nationalists and why the Scottish past has not had the central position in the quest for independence that we might expect.

History and ideology

Scottish nationalists have two considerable advantages in their quest for independence compared to other nationalist movements in Europe. Firstly, Scotland is a clearly defined territory because of its legal system – one can point exactly where England ends and Scotland begins – and this has meant that there is no dispute regarding its border. Indeed, the border with England has hardly changed over the past thousand years or so, and in spite of the warfare of the medieval period, it is one of the most stable in European history.1 As such, Scottish nationalism has not had the problems associated with irredentist nationalism in which the ‘people’ have been separated into other nations or states and a key focus has been to bring them all together. This separation of peoples and ethnicities was one of the major problems with the Versailles Settlement after the First World War as the construction of new nation states did not always geographically align with nationalities.2 While the issue of the right of self-determination of nations was recognized in the post-war treaty and seen as a way of reducing conflict in the future, arguably the Versailles Settlement created as many problems as it solved.3 The legal and territorial rigidity of the definition of ‘Scotland the place’ has meant that ethnic and racial ideas have not risen to prominence as a means to compensate for the lack of precision in a geographical definition of Scotland and the people therein. The fact that the Anglo-Scottish border has been fairly static has massively helped to reinforce this clear territorial identification in terms of national identity. It has also meant that there has not been a politics of reclamation in which lost territory has been a rallying call for nationalists. The partition of Ireland in 1922 is an example close to home where disputed territory has been a driver of nationalist claims.4 Another point worth emphasizing is that there has been little in the way of an English influx into the Scottish borderlands, unlike Wales which has experienced extensive English migration into its eastern regions which has helped dilute Welsh identity in that area.5 In spite of recent claims that there is a ‘borderlands’ identity which encompasses the Anglo-Scottish border, the reality is that cultural identity remains distinctive on either side.6

A second major advantage for those who promote Scottish independence is that they are advocating a polity that has not only existed before but existed for a long time. As many have pointed out, Scotland has been an independent nation for most of its long history since its inception as a kingdom in the 840s. Indeed, it was among the first recognizable nations in Europe.7 As Robert Bartlett pointed out, there were only fifteen established crowns in Europe by 1350, one of which was the Scottish one.8 Although definitions about the meanings of nations and states are complex in the medieval and early modern eras, the fact remains that Scotland was once a nation that had the full panoply of powers and institutions that was normal for a medieval and early modern state, and this history is the foundational bedrock for all arguments about reacquiring Scottish statehood. Put simply, that which once existed can exist once again. Before the Union of 1707, Scotland was an early modern state that had its own monarchy, parliament, army, navy, law and church and had been recognized by other nations as an independent entity by diplomatic protocol and treaties. Having established many of the fundamentals of statehood gave Scottish nationality a maturity, and because the Union was not a conquest which would normally entail an attempt at eradication or assimilation, its nationhood was not extinguished, and indeed, it was preserved both through its institutions and arguably more importantly through its historical memories. It is somewhat axiomatic and therefore tends to be understated, but the idea of the ‘nation’ is fundamental to the existence of most states as the ‘state’ and ‘nation’ are seen as coterminous, the former being an outgrowth of the latter. To be a nation state demands first a nation, and it is Scotland’s history which most clearly defines it as a nation. Crudely put, after the formation of the Scottish nation in the ninth century, it held off subsequent repeated English attempts at conquest and absorption, and this became the dominant theme in Scottish history. A narrative emerged that stressed its fundamental difference to that of its southern neighbour. Scottish architecture, relations with the European mainland and culture, for example, developed in a markedly different way from England, and up until the Reformation, an alliance with France against the English was a key component of Scottish foreign and diplomatic policy.9 Even the emergence of a common bond of Protestantism and the experience of having a shared monarch did not eliminate this sense of difference which was encouraged on both sides of the border.10 For nationalists, the Union of 1707 with England was an aberration in the sense that it interrupted the normal development of the nation into a modern state and that independence would correct this historical anomaly. To coin a phrase, it would put Scotland back on the right historical track. So for Scottish nationalism to evolve as a coherent ideology, it was necessary firstly to make an intellectual case that history clearly demonstrated that Scotland was indeed a nation destined for a sustainable statehood, and secondly, that this historical trajectory was bounced off course in the past, but it could be rectified in the present and future. History matters for Scottish nationalists because for them, the course of history or destiny will not be complete until independence has been attained. Consequently, history serves an important ideological function in accounting for the failure to sustain statehood in 1707, but also crucially demonstrates that the sinews of national development were and are strong enough for the resumption of political independence in the future.

So far, there has been little that has been said that could not be applied to most European nationalist movements regarding the fundamental importance of history.11 This is because it is only through a historical explanation that one can account for the absence of statehood. In most histories of small nations, the reason for the absence of statehood is usually attributed to the imperial aspirations of larger neighbouring countries that have used conquest as a means of territorial aggrandisement and subsequently subverted any demands for independence by the use of superior power. A classic example of this phenomenon is the way in which Irish nationalists constructed a historical account of the nation that explained the connection between Ireland and the mainland as a result of English or Anglo-Saxon imperialism and that the struggle to be free from this domination was the defining characteristic of Irish history.12 Similarities are also apparent in the Polish quest for independence which was sandwiched between Prussian/German and Russian imperial ambitions.13 The ethnic and national tensions within the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its subsequent break-up gave rise to one of the earliest studies in the field of nationalism.14 Although many of the different nationalist accounts of the drive for independence in Europe have similarities, including the tendency to create or highlight what is often seen as a unique or distinctive historical path – Sonderweg, to use the German word – how nationalists construct historical meaning is an important part of their belief system, and to make sense of it, it is necessary to reconstruct such accounts for it provides many of the key points of ideological reference. Because it is such a large topic and its primary function is to serve doctrinal needs, what will be discussed below is necessarily a pared-down version of the nationalist reading of the past. Also, what is being attempted here is an endeavour to outline the main contours of this understanding of Scottish history because there are probably as many versions of the Scottish past as there are Scottish nationalists. Also, there are some hefty disagreements. For some, history is not a major preoccupation; for others, there will be a tendency to highlight some historical interpretations rather than others and sometimes there will be radically different interpretations of the same phenomenon. To illustrate the point, for some nationalists John Knox was a liberator who freed the nation from Catholic superstition, and it shows the nation’s inherent desire for freedom.15 For others, he was an agent of capitalism and Anglo-Saxon imperialism that paved the way for English subjugation16 and for many, someone best avoided because he brings to the surface sectarian tensions that weaken the national movement by highlighting religious divisions within Scotland.17 In short, history and historical events are rarely unproblematic. Forging, in the sense of hammering out and creating, a nationalist history that explains and justifies the cause of Scottish statehood in the present was, and is, one of the key ideological functions of the nationalist movement because even though few discuss it, all nationalists accept without qualification that Scotland is a nation and that its historic destiny is independence. History matters, but its relationship to nationalist ideology is by no means straightforward.

Scottish nationalist ideology has had to work with the body of historical material that had been built up in the nineteenth century before the movement emerged in the 1920s.18 In the main there was a Unionist slant running through most Scottish historiography which tended to point towards the inevitability of the creation of the British state, but at the same time, there was a considerable amount of what might be described as ‘patriotic’ literature which cast the work of Scots and Scotland in a favourable light. By and large, this was mainly a roll-call of the great and good and the many achievements made for the benefit of humanity, science and progress and a contribution to the success of the British Empire.19 What marks out the Scottish historical experience as different from the European norm is an essential part of the Unionist narrative which stresses Scottish independence up until the Union with England in 1707. This means that there is considerable room for a form of historical consensus with disagreement confined to the period in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and beyond. Both nationalists and Unionists accept that an independent nationhood was the norm in Scottish history until at least the Union of the Crowns in 1603 with any differences usually centred on emphasis. Unionists tend to focus on similarities that point the way forward to the Union in the future, such as the shared Protestantism of the Reformation, with those of a nationalist proclivity pointing out the essential distinctiveness of the Scottish experience and would emphasize that whereas the Ref...