The rise in popularity of short-term rentals (STRs) has been widely noted to affect housing affordability, thus presenting itself as a driver of social exclusion in tourist cities. It is also suggested, but less documented, that rent inflation is not the only factor that may be pushing autochthonous residents out of neighbourhoods experiencing intense ‘airbnbization’. Dwelling in STRs unfolds in ways that could be challenging to many aspects of everyday life for a stable population, such as night rest, security, familiarity with neighbours, health, and access to basic services. Our research on such issues is carried out in Vila de Gràcia, a neighbourhood of Barcelona where traditional gentrification is enmeshed with the rising tourist profile of the area. In our fieldwork we examined how residents perceive and cope with such pressures and investigated how (and to what extent) the material hindrances produced by temporary dwelling can trigger the decision to move out.

Introduction

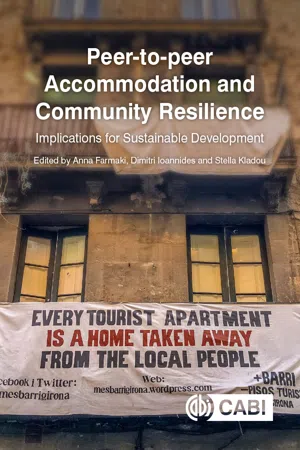

This chapter intends to contribute to the debate on the new avenues of social exclusion that have been unfolding in tourist places in recent years, namely housing exclusion, in relation to the penetration of platform-mediated accommodation. We focus specifically on the mechanisms by which the growth of ‘home-stays’ as short-term rentals (STRs) becomes a source of disruption of the social and population fabric of neighbourhoods. In a burgeoning literature, it is quite well documented that STRs bring about a restructuring of the real estate market. The inflation of rents and housing prices pushes the weakest segments of the population out of the areas of high concentration of tourist rentals (Dredge et al., 2016; Segú, 2018; Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018; Lagonigro et al., 2020). Observers have highlighted that this outcome is substantially driven by rent extraction tactics: (i) proprietors make higher profits and enjoy a more flexible regime of ‘temporary availability’ of their property when they rent houses or rooms in the short-term market (A. Quaglieri-Domínguez, A. Arias Sans and A.P. Russo, 2021, unpublished data); or (ii) ‘buy to let’ (Cócola-Gant and Gago, 2021), which is emerging as a form of ‘spatial fix’ driving the investment strategies of corporate speculators and sectors of the middle classes (Semi and Tonetta, 2020).

Some authors have noted that other neighbourhood transformations are enmeshed with these processes. First is the inflow of transnational ‘nomads’ pushing gentrification. These populations, characterized by mobile biographies and high levels of cognitive capital, select areas offering amenities also sought by urban tourists and increasingly catering to cosmopolitan urbanites and ‘transient’ consumers, often at the expense of the needs and affordability of the incumbent ‘sedentary’ population (Füller and Michel, 2014; Jover and Díaz-Parra, 2019; López-Gay et al., 2020). Second is the ‘signposting’ of certain neighbourhoods as the new speculative frontier in tourist cities, with a fundamental role of the platforms themselves in providing guidance and technical support to area narratives and even home interior design (Bialski, 2016). Rent differentials are thus sustained by symbolic capital, responding to the market opportunities opened by contemporary ‘post-tourist’ practices (Hiernaux and González, 2014).

Cócola Gant (2016) observes that the displacement of original residents from touristified neighbourhoods takes different simultaneous and interrelated forms. The first is direct displacement that occurs with the expulsion of tenants when hotels and tourist apartments are installed in residential spaces. The second refers to displacement by exclusion when the rental or purchase of a home becomes unattainable. The third is the result of difficult coexistence with tourists, affecting the daily life of the residents and leading them to leave the neighbourhood. Finally, the fourth refers to collective displacement, whereby the social transformation of an area prevents the reproduction of residential life. While in-depth studies of the first two processes have followed (González-Pérez, 2019; Ardura Urquiaga et al., 2020; Cócola Gant and López-Gay, 2020; Petruzzi et al., 2020), little attention has appeared in the literature about the narratives and biographies of the population at risk of exclusion in STR-ridden neighbourhoods. One of the few exceptions is A. Quaglieri-Domínguez et al. (2021, unpublished data), who studied the life courses and biographies of the host community established in El Raval, an area of Barcelona characterized by wide ethnic and class heterogeneity. Even before they are actually displaced by the housing market dynamics, these populations may be affected in different ways by the social and cultural change experienced in their livelihood through: (i) marginalization; (ii) erosion of their local ‘support systems’; (iii) disruption of daily routines and rest; and (iv) changes in feelings of security and safety. These processes – possibly constituting (or leading to) emerging forms of social exclusion in a tourist context – are becoming an important element of critical stances towards tourism growth in urban contexts (Novy, 2019).

Recent research on overtourism and its effects (Milano et al., 2019; Salerno and Russo, 2020) has given new life and sense to traditional analytic concepts such as host attitudes towards visitors, as in Doxey’s (1975) evolutionary model leading to antagonism. Yet we still miss a more solid analytic approach to make sense of the interdependencies between elements of social pressure brought about by tourism growth, shifting sensibilities on tourism, and the dynamics of constituencies (displacement, polarization, social and political change). These issues have been explored in Russo and Scarnato (2018) as part of an evolutionary approach to the production of critical discourses with tourism growth, and, in a similar vein, by Richards et al. (2019). The topic of population displacement also touches upon the debate on place resilience. In this sense, we follow a part of the literature that conceives place resilience as a normative and subversive concept (Grove, 2014; Vale, 2014), hinting at the capacity of space to guarantee social reproduction and social justice when exposed to the agency of processes of place transformation such as tourism. Thus, resilient destinations are not those which have a ‘built-in’ capacity to bounce back in terms of performance when subject to external shocks, or to adapt to breakthrough innovations (such as the digitalization of the hospitality marketplace and the related boom of STR), but rather those that in the face of these changes are able to maintain the well-being and inclusion of the community through appropriate policy responses. This ability may well be one of the greatest current challenges for cities in the face of touristification processes (Sequera and Nofre, 2018).

Through our work, we intend to offer a contribution to this regard, exploring in some depth how and to what degree the hindrances brought about by an increasing penetration of STR at neighbourhood level affects certain population groups, and how that may lead them to decide to move out. Towards this end, we carry out a study in a neighbourhood of Barcelona, Vila de Gràcia, which we consider a representative area of the processes under scrutiny.

The chapter is structured as follows. The first section provides the broader canvas of the research on tourism and population change in Vila de Gràcia. We illustrate the trajectory of Barcelona as a successful example of urban regeneration towards being a world-class destination and its eventual ‘overtourism’ crisis. With this backdrop in mind, we situate Vila de Gràcia as a neighbourhood where processes of population substitution are highly enmeshed with its rising profile as an unconventional tourist area characterized by a high level of penetration of STR. In the following section we present our research on community perceptions of tourists dwelling in Vila de Gràcia. This section exploits secondary sources (the municipal survey of residents’ perception on tourism) as well as the information obtained through a survey and some in-depth interviews with a sample of former and current residents; its aim is to reconstruct how different types of residents react to or cope with the increasing numbers of tourists dwelling in their neighbourhood. Finally, in the last section, we discuss the implications of our findings in the light of the existing literature on neighbourhood change, touristification and resilience.

Background: Barcelona Between Urban Restructuring and ‘Airbnbization’

Tourism and social exclusion in Barcelona

Several researchers have explored the issues of tourism’s social impacts in Barcelona. This could be explained by the fact that the Catalan city has experienced a rapid transformation into a global destination since its ‘Olympic period’ at the end of the 1980s, against the backdrop of a social fabric, which at the end of the Francoist period and during the transition to democracy was still characterized by strong polarization (Monclús, 2003; Smith, 2005). The city’s newly gained positioning as an attractive hub for people and capital in the post-industrial global economy has been noted as a successful pioneering effort, bringing together public and private interests in a pervasive programme of urban regeneration. However, at the same time, it has opened new avenues of social inequality that only became apparent after the ‘Barcelona’ model had consolidated and become strongly characterized in terms of tourism growth (Arbaci and Tapada-Berteli, 2012; Degen and García, 2012). Indeed, a new surge in critical research on Barcelona’s urban development has taken place since ‘overtourism’ has become a research buzzword on places. It could actually be claimed that the early works that introduced this term (Milano, 2018; Goodwin, 2019) were directly referring to the case of Barcelona. In this and many other Mediterranean destinations, the concern for tourism excesses intersects critically with the social effects of the global financial crisis of 2008. The economic slump in the Catalan city left a long trail of job losses and impoverishment, and a new dependency on tourism as a ‘recovery strategy’, which ultimately affected the most vulnerable strata of the population who have been helpless in the face of the revalorization dynamics in the housing market. It has also been greatly aided by the progressive deregulation of housing uses and the worsened employment conditions after the ‘anti-crisis’ labour reforms (Russo and Scarnato, 2018).

At the onset of the 2010s, the city presented itself as a global destination that also draws a significant number of day visitors from neighbouring regions – some of Spain’s most popular resort areas – and it is an established haven for ‘mobile populations’ such as foreign students, displaced workers or transient migrants. For the first time in 2016, the city administration estimated that 28.1 million visitors was a realistic estimation of the size of the visitor economy, but also of the pressure generated by this population (Municipality of Barcelona, 2017). The growth of accommodation supply – captured by rates of bed places in all types of establishments per 1000 residents – intensified dramatically in the ‘core’ tourist areas over the last decade. The ratio of 163 beds per 1000 inhabitants registered in the Old City district in 2010 rose to 223 by 2015, and to 265 by 2019. At the neighbourhood level, Cócola-Gant and López-Gay (2020) calculated that in the Gòtic (Gothic) Quarter this ratio goes up to more than 600. This pressure has risen considerably also in other districts that in 2010 were still rather untouched by tourism.

In 2015, the supply of bed places in hotels was 67,603. However, this was now paralleled by an active supply of 59,614 bed places in STRs distributed over 16,700 dwellings, a staggering growth from marginal numbers since the appearance of intermediation platforms like Airbnb in 2012. While the growth of hotel supply is strictly regulated, the enforcement of regulations and the practical possibility to control the expansion of STRs has not kept pace (Lambea Llop, 2017), and Airbnb came to be tagged as the ‘first accommodation chain’ operating in the city in terms of supply. By May 2019, the enforcement of regulations and controls produced a slight contraction of this offer, but the steep growth of dwellings on offer as individual rooms in shared apartments, an unregulated modality of lodging until 2020 (A. Quaglieri-Domínguez et al., 2021, unpublished data), almost balanced this decrease.

The impacts of this kind of growth on the local community need further consideration. Data on household income and rent distribution of resident communities reveal that the situation of such areas with a high density of STRs, mid-to-low-income areas in origin, has not deteriorated significantly under severe tourism stress, and has actually improved in the last few years. However, these areas are also among those having experienced the highest rates of population mobility and substitution. Thus, the image we are seeing regards a neighbourhood population that has substantially changed in the process (see Fig. 1.1a). Registered residents have declined in some of the most intensively tourist areas of the city, like the historical core of the Gòtic, where population loss has been about -14% between 2010 and 2014 (with some census tracts reaching -40%), while in others (like the multi-ethnic El Raval) or the middle-class Dreta de l’Eixample the trend has been reversed and they have actually gained population. By contrast, the low-income national and foreign-born, less-educated population has been pushed out. The number of residents started increasing again in 2015–2019 (Fig. 1.1b), yet the population flowing in to the most intensively ‘touristified’ areas of the city is quite different and could rather be characterized as a wealthier and highly educated new transnational middle class.

The dynamics of the real estate market have indeed been peculiar in the last decade. Purchase prices touched bottom in 2013 because of the fall in demand in the wake of the financial crisis, but economic recovery pushed prices up to pre-crisis levels around 2018. Rental prices reached a new peak in the same year and have continued growing in most neighbourhoods well into 2019 (notably not in the Old City), especially in areas that saw the most intensive development of Airbnb-mediated STRs (A. Quaglieri-Domínguez et al., 2021, unpublished data). Cócola-Gant and López-Gay (2020) comment that the ‘airbnbization’ of housing since 2012 is just one dimension of the speculative pressures leading to neighbourhood change and social exclusion and is enmeshed in wider trends of financialization of real estate capital and commercial assets as the new frontier of neoliberal accumulation strategies. However, the spatial association of the rise of temporary dwellings, housing...