Scholars of the medieval world have long understood the crucial importance of gender as what historian Joan Scott termed a “category of historical analysis” (Scott 1986). In the past, as to some degree remains the case today, ideas about gender shaped social expectations. How should a person behave, in public and in private? What kinds of relationships should they have? What types of jobs should be available to them? In the medieval world, gender also determined legal status. Laws about control over financial resources, sex and adultery, and guardianship of children, to take only a few examples, differed for men and women. Medieval historians have long since abandoned the view that women in the Middle Ages suffered from such grave oppression that they utterly lacked agency. We know that women made decisions about their own lives, sued people in courts of law, worked outside the home, ruled territories large and small, and wrote poems, prose, and prayers. However, women tended to be disadvantaged in relation to men of their same status. Men and women had very different experiences when they worked, married, went to a court of law, or exercised power.

However, gender did not exist in a vacuum: ideas about gender affected different women, and men, in varied ways. Some scholars use the term intersectionality to describe analysis that considers the intertwined impact of factors like gender, race, and class. We can better understand the complicated dynamics that shaped people’s lives in the medieval past if we consider their gender identity in combination with other factors. What socio-economic stratum, or class, did they belong to? Did they live in England, or Italy, or Egypt, or somewhere else in the world? Did they reside in a city or in a rural area? Were they married? What faith did they profess? This book will address many of these points of difference between women, but it will focus on the experiences of Jewish women. As members of a religious minority community, how did they experience the medieval world differently from either Jewish men or from women of other faiths?

Religious identity, like gender, was a legal category, not only a matter of personal faith. During the medieval period, Jews generally lived as a minority community under the rule of another faith—usually either Christianity or Islam. As a minority community, Jews were typically subject to legislation designed to create and reinforce boundaries between people of different faiths as well as to affirm religious hierarchies. Medieval understandings of Jewishness at times blurred the boundaries between faith and ethnicity. While Christians, in particular, pursued efforts to convert Jews to the majority faith, they also expressed concerns that baptism could not in fact fully wash away Jewishness. Jews, for their part, deplored conversion out of the faith but also believed that converts remained part of the Jewish people.

The focus on Jewish women in this book reflects the assumption that we can enrich our understanding of both Jewish history and women’s history through an intersectional approach that incorporates religious identity alongside other forms of difference. Women experienced Jewish life in fundamentally different ways from Jewish men. Jewish law makes divisions based on gender in both religious and social life. Gender also shaped the economic options available to Jewish men and women: Jewish communal and religious authorities had different expectations, rooted in ideas about gender roles, for men’s and women’s work and their control of financial resources. Jewish men and women may have experienced attacks on the Jewish community differently. The institution of Jewish self-governance—usually understood as beneficial to Jewish communities—might not have seemed so unequivocally positive to women, who at times sought justice outside the community. A richer, fuller, and more nuanced Jewish history requires that greater attention be paid to this other half of the Jewish population. Women’s history, too, benefits from a more extensive assessment of the similarities and differences in how gender shaped the lives of women who belonged to a subordinated minority group.

Previous works on medieval Jewish women

Although a growing body of scholarship has focused particularly on medieval Jewish women the specific experiences of Jewish women still tend to receive short shrift in broader surveys on both medieval women’s history and medieval Jewish history. Most surveys on medieval women and gender, even fairly recent ones, have primarily emphasized a Christian European religious and geographical context. Patricia Skinner’s Studying Gender in Medieval Europe: Historical Approaches (2018) incorporates a few passing references to Jews, including a brief discussion of how religious and ethnic identities intersect with gender (Skinner 2018: 140–143). The vast majority of the specific examples that Skinner uses, however, are drawn from Christian European society and culture. The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe (2016), edited by Judith M. Bennett and Ruth Mazo Karras, includes two articles focused on Jewish communities and one on Muslim communities, out of a total of thirty-seven. Bennett’s History Matters: Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism (2006) calls for intersectional approaches that address religious difference in both teaching and research (Bennett 2006: 142–145). However, the examples Bennett draws on throughout the book mostly come out of her own research area of late medieval England, a time and place with no significant Muslim or Jewish communities.

Similarly, overviews of medieval Jewish history and even specialized monographs focused on specific communities usually devote little attention to the distinct ways in which Jewish women experienced the joys and tribulations of pre-modern Jewish life. Surveys often assigned in undergraduate courses, like Mark R. Cohen’s Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (2008), Robert Chazan’s Reassessing Jewish Life in Medieval Europe (2010), and The Jews: A History (2019), a textbook authored by John Efron, Matthias Lehman, and Steven Weitzman, include little discussion of Jewish women. The same can be said of most regionally focused monographs on Jewish communities, including magisterial multi-volume works. General medieval history textbooks, to their credit, include more and more references to Jews and to women, but little or nothing on the specific experiences of Jewish women. All the works mentioned here are excellent surveys—but those interested in Jewish women in particular might be left wanting more information.

However, the overview of medieval Jewish women presented in this volume is only possible because the last several decades have witnessed the development of an increasingly rich body of specialized scholarship focused on Jewish women and gender in the medieval world. In a monumental five-volume study (1967–1993) of the Jewish community of medieval Egypt based on documents from the Cairo Genizah, S.D. Goitein offered a much more comprehensive discussion of women than found in most local and regional studies of medieval Jewish communities. The third volume, entitled “The Family” (1978), focused largely on women’s experiences. In Jewish Women in Historical Perspective (1991), an edited volume containing essays on Jewish women from the Hebrew Bible through the twentieth century, editor Judith R. Baskin called for historical perspectives to inform current understandings and conversations about the role of women in Judaism. Contributions from Baskin, Renée Levine Melammed, and Howard Adelman offered crucial early overviews of medieval Jewish women’s experiences in different regions. All three scholars have also authored other works that have contributed a great deal to our understanding of Jewish women’s lives in the medieval world. Avraham Grossman also published extensively on Jewish women, particularly as seen through the lens of rabbinic sources, in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2001, he published in Hebrew an extensive survey, which was subsequently abridged and translated into English as Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe (2004). This survey has been of great value to students and scholars alike.

Meanwhile, the last two decades have also seen the dramatic growth of the field. Scholars have produced excellent monographs on Jewish women focused on different regions throughout the medieval world. Elisheva Baumgarten’s Mothers and Children: Jewish Family Life in Medieval Europe (2004) and Practicing Piety in Medieval Ashkenaz: Men, Women, and Everyday Religious Observance (2014) both offer insight into the experiences of Jewish women in Ashkenaz, the Hebrew name for a region comprising what is now Germany and northern France. Those interested in the women of Sepharad, the Hebrew name for what is now Spain and Portugal, can turn to works like Melammed’s Heretics or Daughters of Israel: The Crypto-Jewish Women of Castile (1999), on the experiences of women who practiced Judaism in secret, after they or their ancestors had converted to Christianity under duress. In Women, Wealth, and Community in Perpignan, c. 1250–1300: Christians, Jews, and Enslaved Muslims in a Medieval Mediterranean Town (2006), Rebecca Lynn Winer compares the gendered social and economic norms experienced by Jewish, Christian, and Muslim women in the city of Perpignan, which today is located in the south of France but in the thirteenth century belonged to the same political and cultural orbit as the northeastern part of the Iberian Peninsula. Several publications by the late Elka Klein detail aspects of Jewish women’s experiences in Catalonia (2006a; 2006b). Eve Krakowski’s Coming of Age in Medieval Egypt: Female Adolescence, Jewish Law, and Ordinary Culture (2018) crafts a nuanced portrayal of ideas about gender and adolescence in the Jewish communities of the Muslim-ruled Middle East. Works of scholarship like these, as well as numerous articles that explore medieval Jewish gender and women’s history from a variety of perspectives, have made it increasingly possible for general readers and undergraduate students to learn far more about medieval Jewish women than ever before.

The limitations of this work

This work is a synthesis, which means that the amount of detail it can offer is limited, although every effort has been made to distinguish between regions and identify change over time whenever possible. This study also cannot provide a fully comparative perspective relating the experiences of Jewish women to those of their Christian and Muslim counterparts. However, occasional comparative discussions are incorporated. In addition, the Guide to Further Reading includes recommendations for related scholarship focused on Christian and Muslim women’s lives.

The work focuses on the period between 500 and 1500, which in the European context is referred to as the “Middle Ages.” All surveys must take a beginning and end point, and there are certainly pivotal moments around the years 500 and 1500 that justify those as cut-off dates—for example, the 476 fall of the Western Roman Empire, on one end, and, on the other, the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Constantinople and the 1492 conquest of Granada, expulsion of the Jews from Spain, and European exploration of the Americas. Historians have often used these dates to draw boundaries between different historical eras in textbooks and undergraduate courses.

However, it is important to acknowledge that this traditional periodization has its drawbacks. Early modern Europeans coined the Latin term medium aevum, from which are derived the English terms “Middle Ages” and “medieval,” in order to distinguish themselves from their recent ancestors and emphasize their connection to a more illustrious antiquity. They saw themselves as partaking in a “Renaissance”—literally, a rebirth—of classical Greek and Roman culture. Periodization always requires some amount of oversimplification, and in this particular case our periodization relies heavily on how a particular group of intellectual elites saw themselves and their own culture. Today, historians recognize that there is arguably much more continuity than change in the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance or early modern period. In addition, certain developments associated with the Renaissance—for example, a passionate interest in classical antiquity—are also characteristic of the medieval world, and claims that religious intolerance diminished with the Renaissance are patently false.

In this particular case—and many others—the other problem with our traditional periodization is that the boundary dates we choose are fundamentally Eurocentric. Neither the fall of the Western Roman Empire nor the Renaissance, the standard start and end dates for the Middle Ages, is a particularly meaningful turning point in the Islamic context. The more obvious starting point in the Middle East might be the rise of Islam in the early seventh century. The year 1500, meanwhile, falls in the heyday of the Muslim-ruled Ottoman Empire. Moreover, Muslims of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries probably would have viewed the intellectual culture of their ancestors in the seventh to fourteenth centuries not as a “middle” period, but as the dawn of Islam and the classical era of Islamic learning and arts.

However, particularly when acknowledging interconnections and relationships between Europe and the Middle East—connections which included the Jewish communities of both regions—it has become accepted for scholars to employ the term “medieval” when referring to a wider geographic span. Following the example set by recent scholarship on the “global Middle Ages,” this work will refer on occasion to events or individuals dating slightly before and after this period, in tacit acknowledgment of the fact that historical periodization can be better thought of as guidelines than as strict boundaries.

Sources for the study of medieval Jewish women

The growing body of scholarship on medieval Jewish women has drawn on a wide range of source material. Rabbinic sources have offered fruitful insight into communal ideas about gender and—when used carefully—women’s lived experiences. Some of these sources are prescriptive: legal codes that worked to define what women’s role should be in religious life, in the family, and in the economy. However, it is at times difficult to determine the extent to which these laws were followed and enforced in practice.

Rabbinic responsa—questions sent to rabbis and their legal rulings—are particularly compelling sources, in that they shed light on real issues faced by women and their families. However, they should be used with caution due to the fact that they often represent unusual cases. A standard legal conflict would not necessarily require the intervention of particularly learned rabbis, rather than local authorities. Even if a well-known rabbi were consulted, it is possible that their collected responsa do not necessarily preserve all the questions sent to them. When read carefully, responsa can reveal broader ideas about gender roles and norms and illuminate some of the challenges faced by Jewish individuals and communities. But students and scholars should hesitate to assume that an issue described in an individual responsum was common or normal.

Scholars working on the Middle East are particularly fortunate to have at their disposal the extensive and varied source base provided by the Cairo Genizah. In Jewish tradition, a genizah is a repository for waste paper that is inscribed with the name of God. For example, a Torah scroll or prayerbook that has worn out and is no longer usable would be placed in the genizah rather than simply thrown away or repurposed. The Cairo Genizah is of particular interest because that community placed in the genizah seemingly any scrap of paper that contained Hebrew letters. Many are not even written in Hebrew, but in Judeo-Arabic—Arabic transliterated into Hebrew characters. Thanks to the Cairo Genizah, we have a wide range of personal and business letters, marriage and economic contracts, inventories, and more, along with literary, biblical, and philosophical manuscripts.

For scholars working on Christendom, whether in the north or the Mediterranean, personal letters are relatively rare, but a wide array of documentary sources is available. Many of the sources employed by scholars of Jewish women in Christian Europe were produced by institutions associated with the Christian majority: court records and contracts drawn up in Latin by Christian officials and scribes. Although they do not always tell us much about women’s inner lives, they offer a great deal of insight into specific details of women’s lived experiences. Quantitative studies of these sources, made possible in some areas due to the substantial number of surviving documents, allow for assessment of what was normal and what was exceptional for Jewish women.

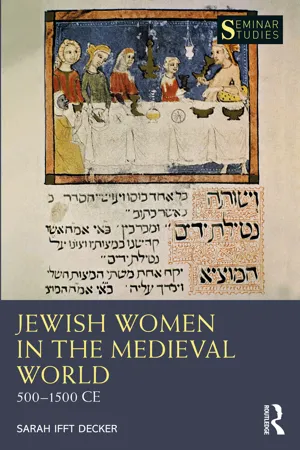

Chronicles and narrative sources—Jewish, Christian, and Muslim—sometimes portray Jewish women, as do visual sources. While these cannot necessarily be taken as accurately reflecting women’s lived experiences, they do tell us about perceptions of gender roles and assumptions—Jewish and non-Jewish—about what Jewish women were or should be like.

Scholars interested in Jewish women’s experiences face particular challenges in that the vast majority of the sources at our disposal were created by men. They must be assessed carefully to avoid making assumptions about whether men’s perceptions or descriptions of women accurately represented their lived reality.