- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

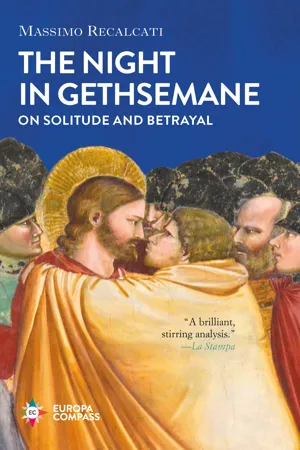

The highly regarded Italian philosopher and psychoanalyst offers "a brilliant, stirring analysis" on suffering, doubt, and the potential for renewal (

La Stampa, IT).

For Massimo Recalcati, Jesus's reckoning in the Garden of Gethsemane is at once an instance of human weakness and an encounter with the Divine. It is the story where the Divine and the Human meet most forcefully, first in company, then in solitude, and where agony and doubt mingle with potential rebirth and revitalization.

As the Gospels recount, after the Last Supper, Jesus retreated to a small field just outside the city of Jerusalem: Gethsemane, the olive grove. His prayers are interrupted when Judas arrives with a group of armed men, and kisses him, betraying and abandoning him with a kiss. Jesus is forsaken by his friends and, it seems to him in this moment, by his father, his God. His sin, in Recalcati's view, is like Prometheus to have drawn Divine closer to man.

"Lively and sharp . . . an invitation to look positively at the loneliness of human experience." — Lettera, IT

For Massimo Recalcati, Jesus's reckoning in the Garden of Gethsemane is at once an instance of human weakness and an encounter with the Divine. It is the story where the Divine and the Human meet most forcefully, first in company, then in solitude, and where agony and doubt mingle with potential rebirth and revitalization.

As the Gospels recount, after the Last Supper, Jesus retreated to a small field just outside the city of Jerusalem: Gethsemane, the olive grove. His prayers are interrupted when Judas arrives with a group of armed men, and kisses him, betraying and abandoning him with a kiss. Jesus is forsaken by his friends and, it seems to him in this moment, by his father, his God. His sin, in Recalcati's view, is like Prometheus to have drawn Divine closer to man.

"Lively and sharp . . . an invitation to look positively at the loneliness of human experience." — Lettera, IT

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Night in Gethsemane by Massimo Recalcati in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Psychoanalysis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE NIGHT

IN GETHSEMANE

INTRODUCTION

Then all the disciples deserted him and fled.

—MATTHEW 26:56

—MATTHEW 26:56

During the night in Gethsemane Jesus is at his most deeply human. This night speaks to us more about the vulnerability of Christ’s life, its finiteness, than it does about crucifixion; it’s about us, about our human condition.

The spotlight is not on the symbol of the cross and the unprecedented violence of torment, torture, and death. During the night in Gethsemane the tragic finale does not yet afflict Christ’s body but, rather, pierces his soul. There are no nails or scourges, no crown of thorns or blows; there is only the weight of a night that will never end, the helpless, bewildered solitude of the life that experiences betrayal and abandonment. This is the night of man, not the night of God. In the course of this night the true passion of Christ is played out: God withdraws into the deep silence of Heaven, refusing to spare his only beloved son the traumatic experience of a fall, of absolute abandonment. The disciples alone remain with him, but, rather than share his anguish, they fall asleep or, like Peter, the most faithful among them, testify falsely on his name, denying him. Jesus is left alone with the soldiers and the temple priests, who want him captured and dead.

The glory of the Messiah, hailed as he joyously enters Jerusalem, is transformed abruptly into an experience of intense solitude. Jesus is accused of a theological outrage: dragging God toward man, confusing what is lacking in man with what is lacking in God; exposing man to a world without God, to the absolute freedom of the creature pushed to the limits of his irreducible distance from God.

During the night in Gethsemane, Jesus doesn’t appear to be the son of God; he’s a delinquent, a common criminal, a blasphemer. No miracle can save him; his life is revealed in a tragic edict of extreme helplessness. What’s important is not the experience of God’s speech—the word of the Father who comes to the aid of his son—but God’s deathless silence, his infinite distance from the son who has been handed over to the wounds of betrayal, political intrigue, the fall, the irreversible, harrowing approach of death.

This book is an attempt to illuminate the scene of Gethsemane in all its details. But why return to the night in Gethsemane? And why, in particular, should a psychoanalyst do so? For me—or rather in myself—the answer is clear: because in this scene the biblical text speaks radically about man, touches the essence of his condition, the condition of man “without God,” his frailty, his lack, his torments. Aren’t the wounds of abandonment and betrayal and the wound of the inevitability of death perhaps the deepest wounds that man has to endure? Isn’t it here that the most radical dimension of a “negative” that no dialectic can redeem is manifested? And doesn’t psychoanalysis constantly confront in its practice and theory this tragic and “negative” dimension of life?

Regardless, in the dark hours of this night we encounter not only our suffering as human beings but also a decisive sign that we must try to deal in an affirmative way with the unavoidable weight of the “negative.” This is what I call the “second prayer” of Jesus. The night in Gethsemane is not, in fact, solely a night of utter abandonment and betrayal, of submissiveness to God’s silence and to the violence of arrest; it is also a night of prayer. But Jesus doesn’t have just one way of praying. During that night he encounters the deepest roots of prayer. And only through this experience of prayer is he able to find an opening that allows him to endure this terrible night: prayer that is not so much an appeal addressed to the Other—a request for help and consolation, an entreaty—but prayer that is the handing over of himself to his own destiny, to the singular Law of his own desire. Isn’t this perhaps the ultimate, most profound, and unexpected meaning of Gethsemane? And isn’t this what’s at stake on every human pathway in life?

It’s the crucial point where, in my view, the lesson of Gethsemane meets the lesson of psychoanalysis: we coincide with our own destiny, decide to give ourselves to our own story, since only in that giving can we uniquely rewrite it, and welcome the otherness of the Law that inhabits us, taking on our condition of lack not as an affliction but as an encounter with what we most intensely are.

Valchiusella, January 2019

This book has its origin in a talk I gave at the Bose Monastic Community on February 25, 2017, under the title The Lesson of Gethsemane.

in the Bose Monastic Community

In the story told by the Gospels, the experience of the night in Gethsemane opens the cycle of the Passion of Christ. Behind him is the joyous entry into Jerusalem, the light of the city that jubilantly welcomes its Messiah. Unarmed, sitting on a donkey and a colt, “the foal of a donkey,” as Matthew recounts (Matthew 21:5), Jesus of Nazareth enters through the gates of the city. The people, the same who will later, at the time of the Passion, stridently call for his death with hatred-charged violence, welcome him joyously, exalting his glory:

Most of the crowd spread their garments on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. And the crowds that went before him and that followed him shouted, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” (Matthew 21:8–9)

During the period between the enthusiastic Hosanna and the dark anguish of Gethsemane, Jesus’ preaching becomes harsher and more radical. Christian subversiveness collides with the codified religion of the priests and their more traditional symbols, including the Temple of Jerusalem. Here we touch on a key point in Jesus’ experience: the power of speech animated by faith tends to clash with its institutionalization. It’s a theme that has been taken up forcefully in psychoanalysis by Wilfred Bion and Elvio Fachinelli: the mystical always comes into conflict with the religious. The thrust of desire and the passion for truth inevitably clash with the institution, which stubbornly defends and preserves its own identity so as to avoid any form of contamination. At the same time, when the free force of speech is institutionalized—is rigidly regimented into an established code—it risks losing its generative power. The history of religions and of every type of School testifies to this: when a doctrine is institutionalized it tends to lose the authentic thrust of desire and the capacity for opening up. Institutionalization coincides with a movement of closure in contrast with the movement of the words, which aspire instead to open up and expand. “Organizing,” as Pasolini would say, prevails in the end over the propulsive thrust of “transhumanizing.”1 That’s why the chief priests of the temple, the scribes and teachers of the Law, become the preferred targets of Jesus’ anger. Entering the Temple, which has become a place of commerce and degradation, he, as Matthew tells us, “drove out all who sold and bought in the temple, and he overturned the tables of the money-changers and the seats of those who sold pigeons” (Matthew 21:12).

Jesus empties the Temple of the objects and idols that fill it, he cleanses it, reopens its “central place” so that it can continue to be a house of prayer. Prayer exists only if there is a “central place,” an experience of emptiness, if the fetishistic presence of the object is eliminated.2 For this reason the institutionalization of faith always carries the risk that it will be assimilated into a formal code of behavior, as the Gospels vividly describe through the image of the sterile fig tree incapable of producing fruit (Matthew 21:18–22). Not surprisingly, Lacan likens Jesus to Socrates, starting precisely from the subversive power of their speech, which can open a breach in the life of the city.3

The fault of the temple priests is that they represent a faith that has forgotten itself, that has lost contact with the potency of desire, that has grown sterile in the exercise of power; they haven’t properly interpreted the stakes of inheritance. Who is a just heir? What does it mean to inherit? What does inheritance of the Law mean? Here is the priests’ greatest fault: they have interpreted inheritance solely as continuity, as formal replication, as ritual repetition of the Same, crushing it through pure conservation of the past. They are, in Jesus’ famous words, “whitewashed tombs, which...

Table of contents

- THE NIGHT IN GETHSEMANE

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR