![]()

1 |Introduction: Maximilian’s Artworlds

Willibald Pirckheimer, learned Nuremberg patrician and close friend of Albrecht Dürer, relates the tale of his five-hour crossing of Lake Constance to Lindau with Maximilian (27–29 July 1499).1 Shortly after a crushing defeat at the hands of “rebellious” Swiss troops at Dorneck during the Swiss Revolt for independence, the emperor determined to dictate the events of his reign (res gestae) in Latin to a secretary. He asked for Pirckheimer’s criticisms of his “soldier’s Latin” (ista militaris latinistas dicteo), an obvious allusion to Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, first published more than a quarter of a century earlier (1469, Rome; 1473 Esslingen). His ambitions were to narrate for historians of posterity.

This Latin autobiography project was short-lived, but from this brief dictation came the germ of all of Maximilian’s literary projects as well as his ongoing relation to the graphic arts that would eventually illustrate them; moreover, from such beginnings stemmed Maximilian’s continual use of scholarly advisers, such as Pirckheimer, to supervise and edit his texts.

Already as early as 1492, the humanist Heinrich Bebel pressed Maximilian to begin a Latin autobiography. In it he charts his life as an oscillation between poles: the misfortune of his natal horoscope, counterbalanced by divine providence (Ergo notandum in posterum est semper deus misericors et e converso spiritus malus constellacionis sue).2 This dialectic lies at the heart of the later plot structure of Teuerdank, Maximilian’s fictionalized, autobiographical, verse romance, and it finds echos in Weisskunig, especially chapter 22, “How the Young White King Learned the Art of Stargazing [Sternsehens]”: “After this the young White King mastered political knowledge. . . . He thought it would be useful to recognize the stars and their influence; otherwise he would not completely understand the nature of men.”3

Joseph Grünpeck, scribe for both the Constance Latin dictation and eventual author of the Latin autobiography, was a cleric and noted Latinist from Ingolstadt, also noted for his astrological prognostications.4 In 1497, he had presented Maximilian with a Latin drama, featuring a morality play in which the monarch himself was asked to choose, like Hercules, between Virtus and Fallacicaptrix, virtue and base pleasure. In August 1498, Grünpeck was crowned a poet laureate by Maximilian. Taken on as a “confidential” or private secretary for the emperor during 1501, Grünpeck was stricken with the effects of syphilis and had to curtail his offices.5 He later added an update to the Latin autobiography, Commentaria divi Maximiliani, covering the years 1501 through 1505 and thus spanning Maximilian’s reign from his Burgundian marriage to the successful conclusion of the Bavarian-Palatine War of Succession. But by this time, Maximilian had already abandoned the use of Latin for his autobiography in favor of the German vernacular. The early outlines of his German allegorical autobiography, consisting of two further books in German, Teuerdank and Weisskunig, can be documented to this period.6 Nonetheless, a final redaction in Latin, the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani, was compiled by Grünpeck and presented to Maximilian with drawn illustrations in Februrary 1516.

These drawings were produced by a young Albrecht Altdorfer, who like Grünpeck lived in Regensburg.7 Chronologically, the Historia drawings end with the emperor’s siege of Kufstein (October 1504), although chapter 36, the final segment of the Latin text, speaks of Maximilian’s forty-ninth year, that is, 1508. The emphasis of these drawings lies more on the interests and activities of the emperor and his father than on their full biographies; virtue and wisdom are the dominant qualities. For Maximilian especially, youthful training, particularly in the martial arts (chapters 5–6) as well as adult accomplishments (including tournaments, masquerades, hunts, and language abilities) within his “open” administration, fill out the illustrations. These feats anticipate the central third of the later Weisskunig text in German, discussing Maximilian’s wide-ranging training, as well as the side towers, also devised by Altdorfer, added to the Arch of Honor, a set of woodcuts that depict the emperor’s personal qualities. At one point in his examination of the Historia drawings, however, even Maximilian clearly found their panegyric excessive. Alongside one drawing (no. 36) he added the remark “better [to have] posthumous praises” (lyber laudis post mortem). Such supervision by Maximilian himself of both text and image is entirely characteristic of his involvement with other artistic projects. He personally lined through two Historia drawings (nos. 12 and 46), both of which adopt the fascination in Grünpeck’s text for celestial portents of the death or advent of great kings—here Frederick III (fo. 30r) and Maximilian (fo. 85r), respectively—because of his own later vision, less favorable to such astrological determinism.8 On two drawings of battle scenes Maximilian notes that a more comprehensive treatment in text and illustrations would appear later and more fully in “weysk,” that is, Weisskunig.9 This notation shows that he was already clearly planning a fuller series of illustrated dictated texts to record his lifetime accomplishments, particularly those most worthy of imperial leadership—victories on the battlefield.

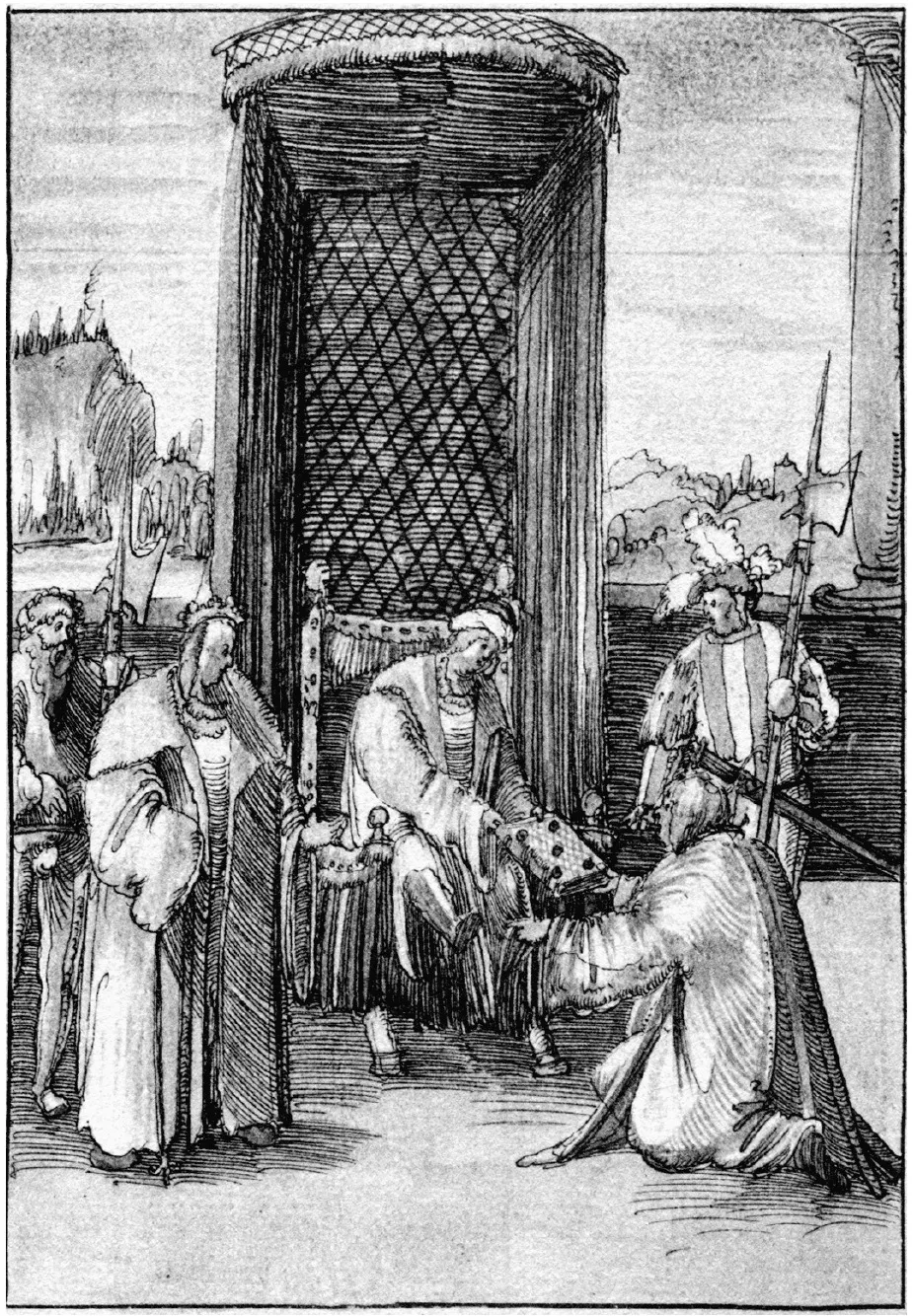

The layout of the Historia drawings suggests a one-to-one correspondence between chapters of text and their illustrations, including, prior to the section on Maximilian, a traditional dedication page illustration (no. 15, fo. 36r; fig. 1), in which the enthroned young grandson and heir, Archduke Charles, to whom the book is dedicated, receives it from the kneeling author, while a proud Maximilian stands beside and looks on.10 In addition to the correspondence of text and illustrations, as in the censored chapters on astrology, Benesch and Auer argue for the supervision and coordination of details by Grünpeck himself.11 Every indication, including the revisions demanded by Maximilian, suggests the real possibility of realizing Grünpeck’s ambition of publishing this Latin text with woodcut illustrations made after the sketchy drawing designs. The author even produced an expanded, second edition, which he offered after Maximilian’s death to his successor in Austria, his grandson, Ferdinand.12

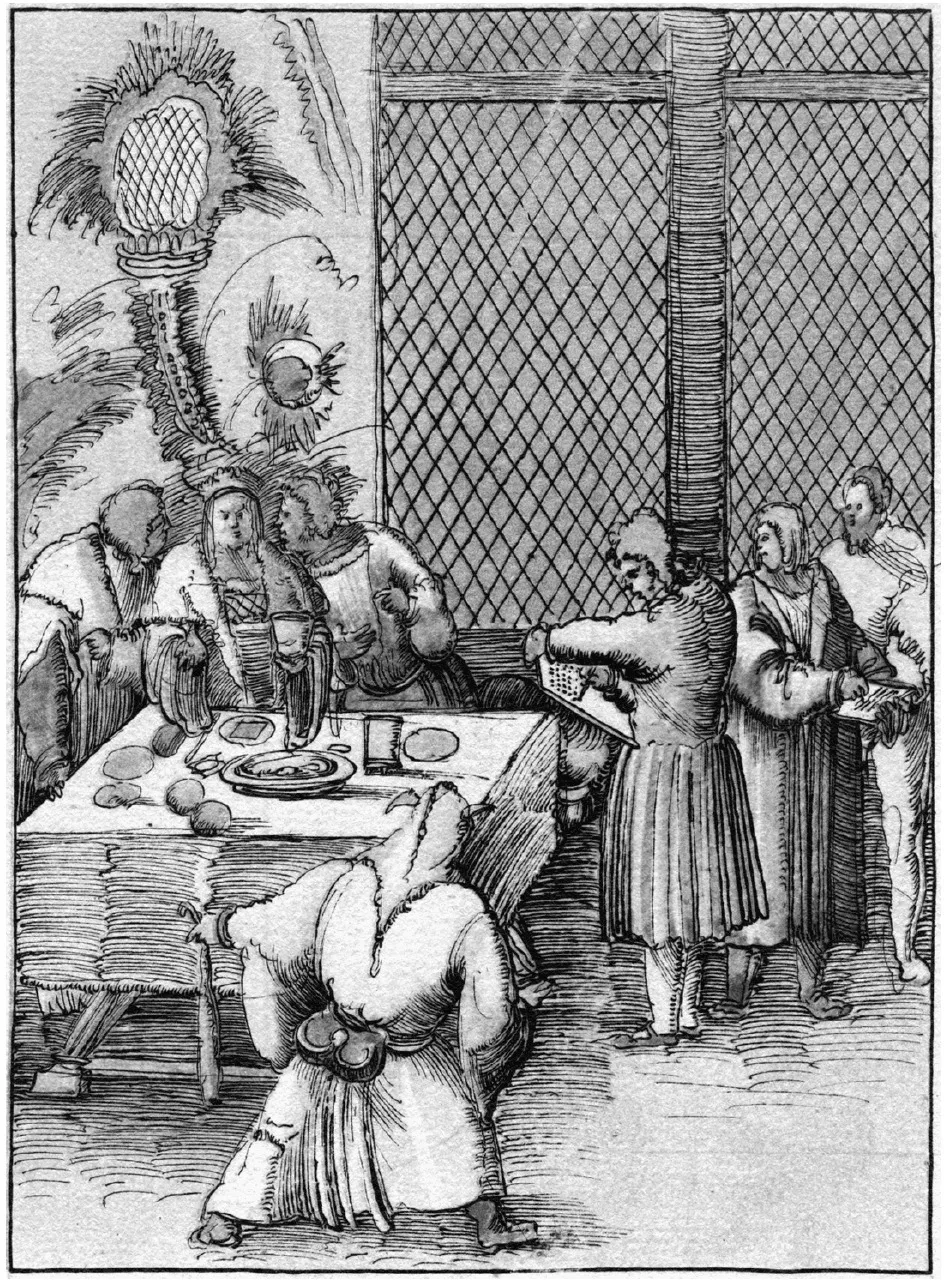

A suggestion of Maximilian’s overall activity with his secretaries is provided within the Historia drawings (no. 42, fo. 79r; fig. 2), where the king, seated at supper before a brocaded cloth of honor with two active, speaking advisers by his side, nonetheless also retains two scribes to record his dictations. In addition, a court fool is depicted entertaining in front of the table, while an extra (military?) court figure stands behind the secretaries at the right edge of the drawing. The accompanying chapter (no. 44) speaks de eius irremissibilibus laboribus, and it amplifies a previous chapter (no. 40), concerning the intelligence and working methods of Maximilian and his court, often exercised during hunts or at mealtimes (this is what is meant by the term “open” administration, utilized above).13 Marginal notations (Hoc etiam pingere), already contained in the original fragment of Latin dictation, indicate an original intention by Maximilian himself to produce an illustrated text. His dictated text of Weisskunig makes this clear: “And thus to make at the outset an explanation of my book I have added painted figures to the text with which the reader with mouth and eye may understand the bases of this painting of my book, which ground I have established, and in the same fashion have written and depicted chronicles, as I have seen such out of other chronicles of my predecessors.”14 Thus, as Grünpeck’s uncompleted Historia project already indicates, the pattern of Maximilian’s literary and visual production of books was already embryonically defined at the very turn of the sixteenth century, and his own ambitions to provide the most modern publishers and graphic artists of print and woodcut found willing collaborators in the roles of secretaries, literary advisers, and artists.

1

Albrecht Altdorfer (attributed), Author Joseph Grünpeck Presents His Text to Archduke Charles, from Historia Friderici et Maximiliani, ca. 1508–10, ink. Vienna, Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchive, Hs. Blau 9, fo. 36r.

2

Albrecht Altdorfer (attributed), King Maximilian Conducts Affairs of State and Other Business While Dining, from Historia Friderici et Maximiliani, ca. 1508–10, ink. Vienna, Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchive, Hs. Blau 9, fo. 79r.

While Grünpeck during his chronic illness was out of sight and mind of Maximilian, the emperor’s literary plans turned around 1505 to his German-language autobiography, to be given the romance-like title, Weisskunig. For this project the center of supervision shifted from Regensburg to Augsburg, and from Grünpeck to Maximilian’s most trusted adviser, Dr. Konrad Peutinger.15 Its title derives from the identification of the hero with his pure, white armor, which contrasts with the identifying arms worn by other kings, dressed in blue (France), green (Hungary), red and white (England), or distinguished by means of heraldic attributes (flints for Burgundy, fish for Venice).16 This tradition derives from courtly romances featuring knights in armor, such as Ulrich von Liechtenstein’s Frauendienst, whose poet-narrator is the “green knight.” Also foundational, the fifteenth-century Burgundian tradition, which Maximilian knew through his marriage (1477) to Mary of Burgundy, provided both fictional romances (Olivier de la Marche, Le chevalier déliberé, 1483; translated into Spanish for Charles V in 1522) and chronologies of splendid reigns (by such historians as Enguerrand de Monstrelet, George Chastellain, and Philippe de Commynes), as powerful models.17

The Weisskunig text was organized along the same lines as the Historia, in three parts: the history (here just the marriage) of Maximilian’s parents; the birth and training of the young Maximilian; and finally, the chronicle of his military campaigns (1477–1513) against his fellow “kings.” As Misch has outlined his ambitions, Maximilian “stylized” the events of his own life in order to provide a melodramatic romance as an apologia for his necessary, yet involuntary, wars as responses to the aggressions of his grasping or envious neighbors. At the same time, those victorious battles, as well as his own education and training, were conceived by Maximilian in terms of an ideal model, suitable for use as a “Mirror of Princes” for emulation by his successors.18

The outlines of the Weisskunig and Teuerdank texts were not dictated directly to Peutinger, but rather were given to a principal private secretary, Marx Treitzsaurwein (d. 1527), a man recorded in documents by 1501 and related to a family of armorers in Mühlau, near Innsbruck (where Maximilian’s armor as well as the bronze statues for his tomb were cast; see chapter 2). The earliest indications of such planned texts appears in a memorandum book, datable to the period 1505–8, where Teuerdank is mentioned (fo. 169r), not yet split off in concept from Weisskunig.19 The earliest redaction by Treitzsaurwein of Weisskunig recounts the youth of Maximilian; it also includes corrections by the emperor.20 In essence, as secretary, Treitzsaurwein fulfilled the role of herald for his master’s deeds, just as a fictional herald, Ehrenhold, the constant companion and witness for Teuerdank, holds the sole duty to sing the praises of his fictional lord. No clear disti...