- 281 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

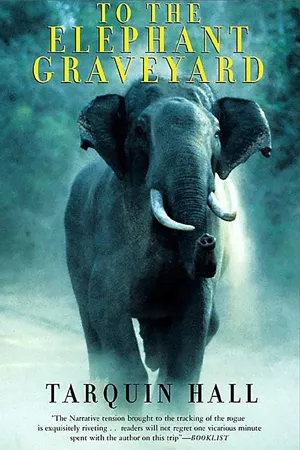

To the Elephant Graveyard

About this book

"Introduces us to the darker side of the Asian elephant. It is more of a thriller than a straightforward travel book . . . insightful and sensitive." —

Literary Review

On India's northeast frontier, a killer elephant is on the rampage, stalking Assam's paddy fields and murdering dozens of farmers. Local forestry officials, powerless to stop the elephant, call in one of India's last licensed elephant hunters and issue a warrant for the rogue's destruction.

Reading about the ensuing hunt in a Delhi newspaper, journalist Tarquin Hall flies to Assam to investigate. To the Elephant Graveyard is the compelling account of the search for a killer elephant in the northeast corner of India, and a vivid portrait of the Khasi tribe, who live intimately with the elephants. Though it seems a world of peaceful coexistence between man and beast, Hall begins to see that the elephants are suffering, having lost their natural habitat to the destruction of the forests and modernization. Hungry, confused, and with little forest left to hide in, herds of elephants are slowly adapting to domestication, but many are resolute and furious.

Often spellbinding with excitement, like "a page-turning detective tale" ( Publishers Weekly), To the Elephant Graveyard is also intimate and moving, as Hall magnificently takes us on a journey to a place whose ancient ways are fast disappearing with the ever-shrinking forest.

"Hall is to be congratulated on writing a book that promises humor and adventure, and delivers both." — The Spectator

"Travel writing that wonderfully hits on all cylinders." — Booklist

"A wonderful book that should become a classic." — Daily Mail

On India's northeast frontier, a killer elephant is on the rampage, stalking Assam's paddy fields and murdering dozens of farmers. Local forestry officials, powerless to stop the elephant, call in one of India's last licensed elephant hunters and issue a warrant for the rogue's destruction.

Reading about the ensuing hunt in a Delhi newspaper, journalist Tarquin Hall flies to Assam to investigate. To the Elephant Graveyard is the compelling account of the search for a killer elephant in the northeast corner of India, and a vivid portrait of the Khasi tribe, who live intimately with the elephants. Though it seems a world of peaceful coexistence between man and beast, Hall begins to see that the elephants are suffering, having lost their natural habitat to the destruction of the forests and modernization. Hungry, confused, and with little forest left to hide in, herds of elephants are slowly adapting to domestication, but many are resolute and furious.

Often spellbinding with excitement, like "a page-turning detective tale" ( Publishers Weekly), To the Elephant Graveyard is also intimate and moving, as Hall magnificently takes us on a journey to a place whose ancient ways are fast disappearing with the ever-shrinking forest.

"Hall is to be congratulated on writing a book that promises humor and adventure, and delivers both." — The Spectator

"Travel writing that wonderfully hits on all cylinders." — Booklist

"A wonderful book that should become a classic." — Daily Mail

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Hit

‘Man and the higher animals, especially the primates, have some few instincts in common. All have the same senses, intuitions, and sensations, similar passions, affections, and emotions, even the complex ones such as jealousy, suspicion, emulation, gratitude and magnanimity; they practise deceit and are revengeful . . .’

Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

The elephant came in the dead of night. At first, he moved silently through the isolated hamlet, past the cottages, bungalows and huts where the inhabitants had long been fast asleep. Past the meeting-house, the fish-pond and the village shop. Past the cigarette stall, the water pump and the temple, dedicated to Hanuman, the monkey god.

The tusker crossed the rickety wooden bridge that spanned the village stream and turned east, following the sandy lane for several hundred yards. Here, he took a short cut over a field, breaking down one or two fences and trampling rows of cabbages underfoot. Soon, he passed another clutch of homes and a primary school.

For some unexplained reason, none of these buildings attracted his attention. Indeed his tracks, when examined the next morning, showed that he failed to stop even once along his chosen path. Instead, he continued to the edge of the settlement, strode straight up to a bamboo hut belonging to a local farmer called Shom, uttered a shrill trumpet and then launched his devastating attack.

Monimoy, a farmer from the same village, was a witness to what happened next. Now, two days later, he sat in the Assam Forest Department’s public affairs office, telling his story to P. S. Das, the information officer whom I had come to meet soon after my arrival in Guwahati.

‘I was making my way home after some drinking,’ said Monimoy. ‘I was walking in the lane when the elephant came. I watched what happened next with my own eyes!’

The farmer scratched at his nose with his index finger and glanced nervously around the gloomy office, sniffing the strong smell of kerosene emanating from a nearby petrol can. His hands shook like those of a junkie gone cold turkey.

‘The elephant’s eyes glowed red. Fire burned inside them. Flames and smoke shot out from his trunk. He was a monster – as big as a house, like one of the gods. His tusks were huge, like . . .’

Das, sitting behind a desk positioned in front of the farmer, was tiring of the yokel’s lengthy and highly coloured story. Impatiently he raised a hand to silence the excited farmer.

‘Just tell us what happened.’

Monimoy fidgeted in his threadbare dhoti.

‘Yes, yes, of course,’ he stammered, ‘I was just coming to that . . .’

He swallowed hard, trying to calm himself, and then continued: ‘The elephant charged at the hut, using his head like a battering ram. Time and again, he smashed into the walls. The timber creaked, snapped and gave way. He smashed at the door with his tusks, breaking it into little pieces. The elephant tugged at the supports with his trunk. Soon the roof caved in!’

Monimoy leaned forward in his chair, nursing his forehead in a manner that suggested he was suffering from a hangover.

‘Inside, Shom’s family screamed for help,’ he continued. ‘I could hear the terrified cries of his daughters. “Help us, help us, ” they pleaded. “The elephant is attacking us!”’

Monimoy had watched from the lane, drunk and helpless. Rather than going to the rescue, he remained frozen to the spot.

‘I couldn’t move,’ he stammered, shaking his head from side to side regretfully. ‘I couldn’t do anything.’

It took the elephant only a few minutes to flatten the flimsy structure. Amidst the confusion, a lantern was knocked over, setting fire to the dry straw roof. Within seconds, the hut was engulfed in flames. Two of Shom’s daughters escaped out of the back, running across the fields to the safety of a neighbour’s cottage; another daughter and her mother hid in a nearby ditch. Sadly, Shom was not so fast on his feet.

‘Shom was drunk. He stumbled out of the hut clutching a machete. I could see the terror on his face. He called out for someone to save him. This got the elephant’s attention and he came after Shom.’

With shaking hands, Monimoy paused to pick up a mug of milky tea that stood on the desk before him.

‘Shom tripped and fell on the ground. The elephant grabbed hold of him with his trunk. Shom struck out with his machete. The elephant knocked it from his hand.’

As he talked, Monimoy began to sweat openly. He shut his eyes tight as if the memory of what happened next was too much to bear.

‘Shom was screaming and screaming. I can hear him now! He struggled to get free. The elephant held on to him and swung him around and then smashed him against a tree again and again.’

The elephant toyed with the local farmer, like a cat playing with a mouse, before dropping him on the ground. Remarkably, Shom was still conscious. He groaned in agony as blood seeped from his mouth and nose.

The triumphant beast stood over him, raised his trunk and trumpeted angrily. Then he prepared to finish off his victim.

‘What happened next?’ prompted Das impatiently.

Monimoy swallowed again.

‘As I watched,’ he said, ‘the elephant knelt down and drove his right tusk straight through Shom’s chest!’

Das grimaced. I shifted uneasily in my chair. Monimoy looked off into space, as if in a trance.

‘For a moment, Shom writhed around. After that, he was still.’

The rogue elephant raised his tusk with the farmer still pinned to its end like a bug on the end of a needle.

‘Then the elephant tossed him to one side and disappeared into the darkness, the blood dripping from his tusk.’

Two days earlier, on the morning of Shom’s death, I had been reading the newspapers in my office at the New Delhi bureau of the Associated Press when the following article caught my eye:

Rampaging Rogue Faces Execution

Guwahati: The government of Assam today issued proclamation orders for the destruction of one wild rogue elephant, described as Tusker male, who is responsible for 38 deaths of humans in the Sonitpur district of Upper Assam.

The state Forest Department has therefore invited all hunters to come forward and bid for the contract worth 50,000 rupees.

The favoured candidate is one Dinesh Choudhury of Guwahati. In reply today to a question about whether he would accept the assignment, he said:‘It is a very dangerous thing. It will take some time before the elephant can be brought to task. We will have to travel on tamed elephants into the jungle areas and flush him out.’

The deadline for candidate application is tomorrow at 5:30 p.m.

Tearing the article from the paper, I reread it carefully. It sounded like one of the most promising stories I had come across for months. Who would have imagined, in this day and age, that the Indian authorities were hiring professional hunters to slaughter Asian elephants, which are more usually regarded as an endangered species? Surely, with modern tranquillizers, an elephant could be captured and placed in a zoo or, at the very least, driven into a game reserve? No doubt, I mused, corruption lay at the heart of the matter. If I had the chance to travel to Guwahati, the capital of the state of Assam, I sensed that I might be able to expose what sounded like an underhand business.

There was just one problem. The elephant was on the rampage in North-East India, an obscure part of the country rife with insurgency. The region was periodically off-limits to foreigners. In the past, I had been barred from going there. I decided to call Assam’s representative in Delhi who made it clear that the regulations had been relaxed.

‘I cannot guarantee your safety or offer any protection,’ he said, ‘but you are free to travel anywhere in the state, except military areas.’

That was good enough for me. I called my editor in London, sold him the story and explained that I might be away for as much as a fortnight. After that I booked myself on the next Indian Airlines flight to Guwahati.

Now, sitting in Das’s office, I considered Monimoy’s fantastic tale. It seemed implausible. Elephants do not breathe smoke and fire, they are not gods, and they certainly do not go around in the middle of the night knocking down people’s homes and singling out particular human beings for premeditated murder. Elephants are kindly, intelligent, generally good-tempered creatures, like Babar or Dumbo. Monimoy, who had by his own admission been drinking at the time of the attack, was clearly prone to wild exaggeration. But could he also be lying?

My suspicions aroused, I questioned him carefully about his motives for travelling all...

Table of contents

- To the Elephant Graveyard

- By the same author

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Epigraph

- Map

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- Author’s Note

- Bibliography

- Illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access To the Elephant Graveyard by Tarquin Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.