- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This "seriously entertaining book" explores the skin in its multifaceted physical, psychological, and social aspects (

Times, UK).

Providing a cover for our delicate bodies, the skin is our largest and fastest-growing organ. We see it, touch it, and live in it every day. It is a habitat for a mesmerizingly complex world of micro-organisms and physical functions that are vital to our health and survival. One of the first things people see about us, skin is also crucial to our sense of identity. And yet much about it is largely unknown to us.

With rigorous research and lucid prose, Monty Lyman explores our outer surface through the lenses of science, sociology, and history. He covers topics as diverse as the mechanics and magic of touch (how much goes on in the simple act of taking keys out of a pocket and unlocking a door is astounding), the close connection between the skin and the gut, what happens instantly when one gets a paper cut, and how a midnight snack can lead to sunburn.

The Remarkable Life of the Skin takes readers on a journey across our most underrated and unexplored organ. It reveals how our skin is far stranger, more wondrous, and more complex than we have ever imagined.

Providing a cover for our delicate bodies, the skin is our largest and fastest-growing organ. We see it, touch it, and live in it every day. It is a habitat for a mesmerizingly complex world of micro-organisms and physical functions that are vital to our health and survival. One of the first things people see about us, skin is also crucial to our sense of identity. And yet much about it is largely unknown to us.

With rigorous research and lucid prose, Monty Lyman explores our outer surface through the lenses of science, sociology, and history. He covers topics as diverse as the mechanics and magic of touch (how much goes on in the simple act of taking keys out of a pocket and unlocking a door is astounding), the close connection between the skin and the gut, what happens instantly when one gets a paper cut, and how a midnight snack can lead to sunburn.

The Remarkable Life of the Skin takes readers on a journey across our most underrated and unexplored organ. It reveals how our skin is far stranger, more wondrous, and more complex than we have ever imagined.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Remarkable Life of the Skin by Monty Lyman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Dermatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Swiss Army Organ

The many layers and lives of our skin

‘The task is not so much to see what no one has yet seen; but to think what nobody has yet thought, about that which everybody sees.’

ERWIN SCHRÖDINGER

WE SEE SKIN all the time, both on ourselves and on others. But when was the last time you really looked at your skin? You might give it a regular inspection in the mirror, part of a daily skincare routine, but I mean properly looked. And wondered. Wondered at the elaborate, unique whorls carved on the tips of your fingers, and at the furrows and hollows of the miniature landscape on the back of your hand. Wondered at how this wafer-thin wall manages to keep your insides in and the treacherous outside out. It’s scratched, squashed and stretched thousands of times a day, but it doesn’t break – at least not easily – or wear out. It’s battered by high-energy radiation from the sun, but stops it from ever touching our internal organs. Many of the deadliest members of the bacterial hall of fame have visited the surface of your skin, but rarely do they ever get through. Though we take it for granted, the wall the skin creates is utterly remarkable and it’s constantly keeping us alive.

Never is the skin’s importance more apparent than in the rare but nonetheless sobering tales of when skin fails. Thursday, 5 April 1750 was a quiet spring morning in Charles Town (now Charleston), South Carolina, but the newly ordained Reverend Oliver Hart was on his way to an emergency. Hart was an uneducated carpenter from Pennsylvania who had caught the attention of church leaders in Philadelphia and, at the age of twenty-six, was offered the role of pastor at Charles Town’s First Baptist Church. (He would go on to become an influential American minister.) His diary is a humbling time capsule of the trials of eighteenth-century American life: rampant disease, hurricanes, and skirmishes with the British. In one of the diary’s first entries, written a few months into his ministry, Hart records the details of that emergency morning visit, to the newborn child of a member of his congregation, because what he found was unlike anything he had ever seen before:

It was surprising to all who beheld it, and I scarcely know how to describe it. The skin was dry and hard and seemed to be cracked in many places, somewhat resembling the scales of a fish. The mouth was large and round and open. It had no external nose, but two holes where the nose should have been. The eyes appeared to be lumps of coagulated blood, turned out, about the bigness of a plum, ghastly to behold. It had no external ears, but holes where the ears should be … It made a strange kind of noise, very low, which I cannot describe. It lived about eight and forty hours, and was alive when I saw it.1

This diary entry is the first recorded description of harlequin ichthyosis, a rare and devastating genetic skin disorder. A mutation in a single gene, called ABCA12, reduces the production of the bricks (the proteins) and mortar (the lipids) that make up the stratum corneum, our outermost layer of skin.2 This abnormal development results in areas of thickened, fish-like scales (ichthys is the Ancient Greek word for fish) with unprotected cracks in between. Historically, infants with harlequin ichthyosis would die within days from the broken barrier as it let out the good stuff – leading to severe water loss and dehydration – and let in the bad stuff – namely, infectious agents. Without the skin’s tight regulation of body temperature, the condition also poses a continual risk of either life-threatening hyperthermia or equally life-threatening hypothermia (being too hot or too cold, respectively).3 There is still no cure for this life-shattering disease, although modern intensive treatment to repair barrier functions now enables some of these children to live into adulthood, albeit with constant medical dependence.

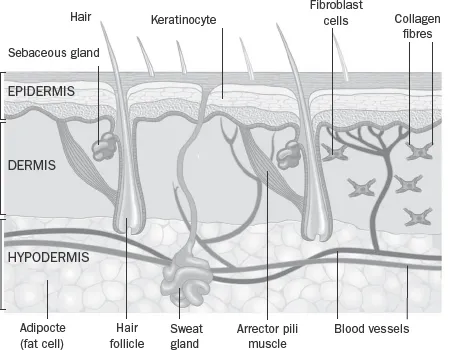

We so easily take for granted the countless roles our most diverse organ plays in our lives, let alone its seemingly prosaic function as a barrier. But an abnormally formed skin can be a death sentence. To begin to fathom the beauty and complexity of our largest organ, imagine hopping into a microscopic mine cart and descending through the skin’s two distinct but equally important layers: the epidermis and the dermis.

The outermost layer, lying on the very edge of our body, is the epidermis (literally, ‘on the dermis’). It is on average less than 1mm thick, not much thicker than this page, yet it carries out almost all the barrier functions of our skin and survives all manner of damaging encounters, which it is exposed to far more often than other body tissue. Its secret lies in its multi-layered living brickwork: keratinocyte cells. The epidermis is made up of between fifty and one hundred layers of keratinocytes, named after their structural protein, keratin. Keratin is unbelievably strong: it forms our hair and nails, as well as the unbreakable claws and horns found in the animal kingdom. The word itself comes from the Ancient Greek for horn, keras (from which we also get rhinoceros). If you were able to zoom in on the back of your hand to about 200x magnification you would see tough, interlocking keratin scales resembling an armadillo’s armour. This biological chainmail is the culmination of the remarkable life story of the keratinocyte.

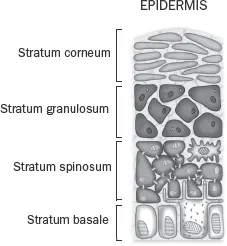

Keratinocytes are produced in the deepest, basal layer of the epidermis, the stratum basale, which lies directly on top of the dermis. This vanishingly-thin layer, sometimes just one cell thick, consists of stem cells that are continuously dividing and renewing themselves; every skin cell on our surface originally bubbled up from these mysterious springs of life. Once a new keratinocyte is created, it slowly moves upwards to the next layer, the stratum spinosum, or spiny layer. Here, these young adult cells start to link up with adjacent keratinocytes via intensely strong protein structures called desmosomes. They also start to synthesize different types of fat within their cell body, which will soon provide the all-important mortar in our skin’s outer wall. As the keratinocytes ascend to the next layer, they make the ultimate sacrifice. In the stratum granulosum, or granular layer, the cells flatten, release their fats and lose their nucleus, the cell’s gene-containing brain. With the exception of red blood cells and platelets, all of the cells in our body need a nucleus to function and survive, so when keratinocytes finally reach the top layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, they are effectively dead – but they have realized their purpose: this infinitesimally slim layer is the body’s barrier wall. The living keratinocytes have become hard, interlocking plates of keratin, and the surrounding fatty mortar makes our surface as waterproof as a waxed jacket. Eventually, at the end of their month-long life, chipped away by the scratches and scrapes of the outside world, these scales flake off into the atmosphere. But this loss does not compromise the epidermal wall, with younger cells continually rising upwards to have their turn to face the world. Keratinocytes create a fine but formidable outer defence, protecting the trillions of cells inside our body. Never was so much owed by so many to so few.

THE LAYERS OF THE SKIN

LAYERS OF THE SKIN

An extra, fifth layer of epidermis is found in thicker areas of skin, namely the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The stratum lucidum (clear layer) is four to five cells thick and sits just beneath the stratum corneum. Composed of numerous dead keratinocytes containing a transparent protein called eleidin, this extra layer helps the skin at the working ends of our limbs cope with constant friction and stretching.

Coated in antimicrobial molecules and acids, the outer defences of the epidermis are chemical as well as physical, designed to keep out unwanted visitors, from insects to irritants, and to keep in moisture.4 A watertight barrier is essential for life. In the grisly (and thankfully mostly historical) cases of humans being flayed alive, they ultimately suffered death by dehydration. When burns victims lose the majority of their skin surface, they require enormous amounts of fluids (sometimes more than 20 litres a day) to stay alive. Without our envelope of skin, we would evaporate.

The epidermis might be a wall, but it’s also constantly in motion, the stem cell springs of the stratum basale always pumping out new skin cells. Although an individual human sheds more than a million skin cells each day, making up roughly half the dust found in our homes,5 our entire epidermis is completely replaced each month, yet remarkably this endless state of flux doesn’t cause our skin barrier to leak. This fundamental secret of the skin was discovered by means of a slightly peculiar postulation.

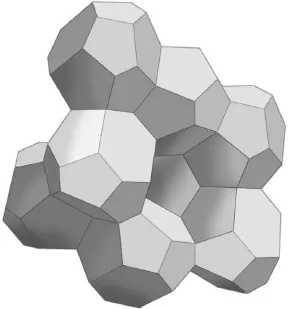

By 1887, Lord Kelvin, the Scottish mathematician and physicist, was already famous for his innumerable scientific discoveries, not least determining the value of temperature’s absolute zero. But in his later years he sought to discover the perfect structure for foam. This odd proposal aimed to address a previously unasked mathematical question: what was the best shape to enable objects of equal volume to fill a space yet have the smallest amount of surface area between them? Although his work was dismissed as ‘a pure waste of time’ and ‘utterly frothy’ by his contemporaries, he worked his way through intense calculations, finally proposing a three-dimensional fourteen-face shape that when positioned together formed a beautiful honeycomb-like structure.6

The hypothetical ‘tetradecahedron’ doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue, and for a century it seemed that Kelvin’s contribution had no relevance to either material science or the natural world. Then, in 2016, scientists in Japan and London, with the help of advanced microscopy, took a closer look at the human epidermis.7 They discovered that as our keratinocytes rise up to the stratum granulosum before their final ascent to the surface, they adopt this unique fourteen-face shape. So even though our skin cells are always on the move before flaking off, the surface contacts between cells are so tight and ordered that water still cannot get through. It turns out that our skin is the ideal foam. Like the intricate geometric tiles seen in medieval Islamic architecture, our skin combines function and form to make a beautiful barrier.

TETRADECAHEDRON

When our outer wall is repeatedly beaten and battered, our epidermis responds by going into overdrive, and anyone whose epidermis suffers repeated rubbing is likely to have calluses, from builders to rowers. I have a friend who, when he is indoors, will always be found strumming away on his guitar; whenever he is outdoors he climbs unfeasibly vertiginous rock faces. The wear and tear from both of these activities have prompted the keratinocytes in his epidermis to proliferate at a much higher rate than average, giving him hard, thickened calluses over his fingers and thumbs.

Callus formation – hyperkeratosis – is a healthy, protective response from our skin when it needs to reinforce the wall. But an unwanted overproduction of keratinocytes can lead to numerous skin conditions. Roughly one in three people have experienced the ‘chicken skin’ of keratosis pilaris, where tiny, flesh-coloured bumps cover most commonly the upper arms, thighs, back and buttocks, looking like permanent goosebumps and feeling like rough sandpaper.8 This inherited condition is caused by an excess of keratinocytes covering up and plugging hair follicles, forcing the shaft of the hair to grow within its sealed tomb.

Keratosis pilaris is harmless and usually has little effect on quality of life, but this isn’t true for all hyperkeratotic conditions. In 1731, a man called Edward Lambert was exhibited in front of the Royal Society in London. His skin (save for his face, palms and soles) bristled with black, crusty spines caused by extreme hyperkeratosis. The ‘Porcupine Man’, as he was dubbed, seemed to be the first of his kind. Lambert could only gain employment in a travelling circus touring Britain and Europe, and in Germany he picked up the equally undignified title of ‘Krustenmann’ – literally, ‘Crusty Man’. He lives on in the modern name for this exceedingly rare disease: ichthyosis hystrix – hystrix being the Ancient Greek for porcupine.

Aside from rare genetic diseases, failures of the epidermis’s all-important barrier function are also seen in more common conditions. In Europe and the USA, a fifth of children and a tenth of adults are affected by atopic dermatitis (the clinical name for eczema).9 Ranging from mildly irritating dryness and itching to a life-ruining disease, eczema was long thought to be a purely ‘inside-out’ condition, with an internal imbalance in the immune system damaging the skin.10 However, a study in 2006, led by a team at the University of Dundee, found that mutations in the gene that carries the code for the protein filaggrin were strongly associated with eczema.11 Filaggrin is essential for the integrity of the barrier of the stratum corneum. It keeps the dead, interlocking keratinocytes close together as well as naturally moisturizing this layer. A loss of this protein creates cracks that weaken the wall, letting allergens and microbes from the environment into the skin and causing water to leak out. This ‘outside-in’ model suggests that eczema (or at least many cases of it) is caused by structural impairments in the skin barrier, rather than internal immune dysregulation. It may also explain why people with eczema experience seasonal skin changes. A study published in the British Journal of Dermatology in 2018 found that in the winter – in northern latitudes, at least – the amount of filaggrin produced was reduced and the cells of the stratum corneum shrank in the cold, reducing the effectiveness of the barrier.12 This helps explain why eczema worsens in the cold of winter, with researchers advising extra protection with emollients over this period for those at risk. About half of people with severe eczema have a mutation in the filaggrin gene, and while it’s not the only reason for this complex disease – the outside environment and internal immune system are other causes – we now know that barrier dysfunction is a prime factor.

Despite the epidermis being the most accessible part of our most accessible organ, we are still discovering its secrets. In recent years it has become evident that the epidermis is more dynamic than ever imagined. A new body of evidence suggests that skin cells contain complex internal clocks that run on a twenty-four-hour rhythm influenced by the body’s ‘master clock’, which sits ticking away in an area of the brain called the hypothalamus.13 Overnight, keratinocytes proliferate rapidly, preparing and protecting our outer barrier for the sunlight and scratches of the coming day. During the day, these cells then selectively switch on genes involved with protection against the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays. A 2017 study took this one step further and found, rather remarkably, that midnight feasts could actually cause sunburn.14 If we eat late at night, our skin’s clock assumes that it must be dinner time and consequently pushes back the activation of the morning-UV-protection genes, leaving us more exposed the next day. So while studies are increasingly showing that a lack of sleep is detrimental to our overall physical and mental health, it now seems that our skin also benefits from additional sleep. The epidermis may be built to face the outside world, but it’s increasingly clear that it also looks inwards, even at when we choose to eat.

Below the epidermis lies a very different layer: the dermis. The dermis makes up most of our skin’s thickness, and it is a hive of diverse activity. Think of the epidermis as a factory roof, from where it’s possible to look down on to a bustling workshop. Cables of nerve fibres and pipes of blood and lymph vessels snake around towering protein supports, the whole scene populated by an equally varied workforce of specialized cells.

While keratinocytes are the predominant cells of the epidermis, arguably the most important cells in the dermis are the fibroblasts – the construction workers. These cells produce pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- 1 The Swiss Army Organ

- 2 Skin Safari

- 3 Gut Feeling

- 4 Towards the Light

- 5 Ageing Skin

- 6 The First Sense

- 7 Psychological Skin

- 8 Social Skin

- 9 The Skin That Separates

- 10 Spiritual Skin

- Glossary

- References

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- Back Cover