- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The narrative grotesque in medieval Scottish poetry

About this book

The Narrative Grotesque examines late medieval narratology in two Older Scots poems: Gavin Douglas's The Palyce of Honour (c.1501) and William Dunbar's The Tretis of the Tua Mariit Wemen and the Wedo (c.1507). The narrative grotesque is exemplified in these poems, which fracture narratological boundaries by fusing disparate poetic forms and creating hybrid subjectivities. Consequently, these poems interrogate conventional boundaries in poetic making. The narrative grotesque is applied as a framework to elucidate these chimeric texts and to understand newly late medieval engagement with poetics and narratology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The narrative grotesque in medieval Scottish poetry by Caitlin Flynn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Palyce of Honour, Gavin Douglas

1

‘Overset with fantasyis’: grotesquing the dream vision

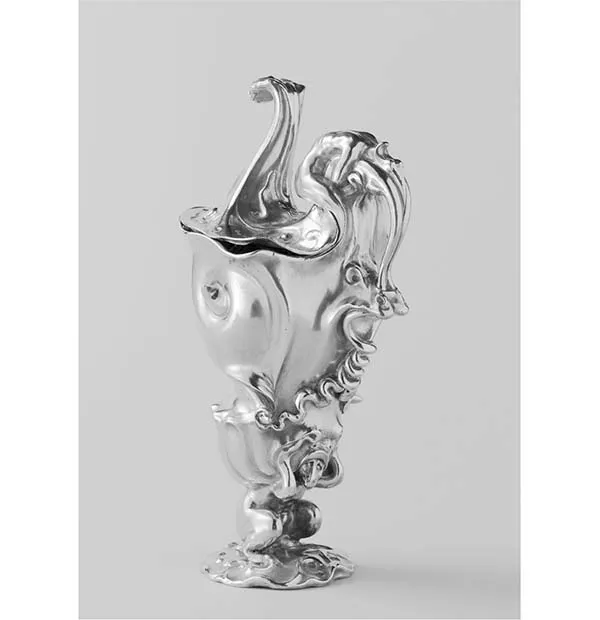

Here the cup becomes as liquid as its contents, and as one improbable form follows another, it seems as though it is only the artist’s inspired improvisation that prevents the whole thing from a sudden collapse into formlessness. The actual creation of this ewer was, of course, anything but improvisational. Van Vianen painstakingly hammered out these forms from a single disk of silver, and it is a testament to the artist’s virtuosity that we read the finished object as a whimsical caprice.1

Adam van Vianen’s Lidded Ewer (1614) morphs from sea monster to maiden, maiden to water, water to shell, and finally a simian figure supports the fluid fantasy (Figure 1.1). Connelly observes that the audacious enhancements to the jug overspill its functionality, and exposes van Vianen’s ‘final trump to the presumptions of those who insist on using this simply as a functional cup: the pleasure of the unsuspecting drinker, savoring the last delicious drop, evaporates with the discovery of two salamanders at the bottom of the cup!’2 Connelly’s remarks highlight the striking relationship between creator, creation, and audience in the grotesque object. The grotesque fluidity and improvisation of the object is possible only by means of the extreme ingenuity and control of its creator. And, even when the insistent viewer crushes the unruly form into conventional categorisation, it resists belligerently. Gavin Douglas’s The Palyce of Honour (c. 1501) achieves a similarly chaotic, boundary-fracturing narrative grotesque through Douglas’s manipulation and innovation of the medieval dream vision genre.3

This chapter undertakes a forensic analysis of Douglas’s treatment of the conventions long established in the medieval dream vision genre. The discussion takes into account the status of dream vision poetry in medieval thought and writing with a particular focus on the setting and mood first instigated in Palyce’s frame and pursued in the dream. Crucially, Douglas’s genre-breaking narrative frequently betrays distinctly humanist overtones. These tones exemplify the significant transformations in philosophy and aesthetics that were taking place in Scottish writing in the later fifteenth century. The narrative grotesque accommodates these clashing ideologies by offering a framework with which it is possible to identify the medieval boundaries that are distorted and overspilled by ground-breaking humanist modes of thinking.

Figure 1.1 Lidded ewer for the Amsterdam Goldsmiths Guild (1614). Adam van Vianen. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, BK-1976-75. Public domain.

The disruptive nature of Douglas’s narrative is, moreover, dependent on sensory experience: rather than awakening to a locus amoenus, Douglas’s dreamer encounters a confusing and apocalyptic landscape which is itself disrupted by the divine courts that process through the wilderness. The tripartite narrative arc explores questions relating to poetic identity, the role of poetry in the world, and the relationship between the worldly and the divine. Reflections and multiplications are inherent to the narrative and the repetition of threes is repeated on a large scale, as evident in the poem’s overarching organisational structure, and also in the minutiae, as demonstrated by the three three-stanza poems created by the dreamer at important transformative moments in the dream. The resulting echoes add ever-increasing levels of complexity to an already dense and enigmatic work. Douglas’s exploration of his dreamer-narrator’s mental processes and perceptions forms a grotesque experiment in dialectic. As a result, Douglas achieves a sense of grotesque fluidity reminiscent of van Vianen’s Lidded Ewer whereby forms and expectations seem to transform before the eyes of the audience.

Medieval dream visions

Dream visions offered varied and flexible settings for authors to explore questions of epistemology within a deeply personal and introspective frame. The phenomenon of the dream, and by extension the literary dream vision, however, posed problems for writers, who were forced to grapple with the extent to which they could be trusted as sources of insight or knowledge. On one hand, dreams might be attributed to poor digestion, while on the other hand they might be prophetic visions of divine origin. Beyond their wide transmission across the medieval West, Macrobius’s early fifth-century Commentary on the Dream of Scipio and Calcidius’s late fourth-century Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus are useful barometers of medieval attitudes towards dream visions, since they provide what Steven Kruger terms a ‘middle way’ between the two extremes: ‘Rather than asserting that all dream experience was either divine or mundane, such authors took a more inclusive approach, accepting the possibility that, under different sets of circumstances, both divine (externally inspired) and mundane (internally stimulated) dreams can occur.’4 The inherent ambiguity and flexibility of the dream vision poem, as suggested by the dream’s ambivalent treatment by Macrobius and Calcidius, is magnified in Douglas’s interpretation of the form. Despite the almost rote nature of literary dream visions by the opening of the sixteenth century, Douglas affects an innovative take on the form by incorporating humanist perspectives into the popular medieval mode.

Despite their waning popularity across the rest of Europe, dream visions were a popular mode in Scotland in the fifteenth century. Two pre-eminent Scottish makars, William Dunbar and Robert Henryson, engage the genre, while several other works further prove the ubiquity of the form.5 Dunbar and Henryson contrive dream visions that push and pull at generic conventions, but Douglas’s composition is unique: it creates a dream vision that functions as all five categories of vision as proposed by Calcidius in his commentary on Timaeus. Calcidius summarises the five types:

a dream, which we said arises out of vestigial disturbances within the soul; a vision, the kind that is ushered in by a divine power; an admonition, when we are guided and admonished by the counsel of angelic goodness; a manifestation, e.g., when a celestial power makes itself openly visible to us during waking hours, ordering or forbidding something in awe-inspiring form and speech; a revelation, whenever the secrets of a coming event are revealed to those who are ignorant of what the future holds in store.6

Palyce embodies each of these possibilities. The narrator’s soul is clearly disturbed, as demonstrated through the apocalyptic landscape in which he wakes; the visionary aspect, conversely, is slowly revealed as the dreamer transforms into the narrator and learns to interpret the events of the dream; a celestial power makes itself known in voice and sign with the disembodied voice and meteor of the frame, which so terrify the dreamer that he faints into the vision; the revelation might be linked to Venus’s command to the dreamer to translate a ‘buke’ for her.7 Equally, Honour’s brief appearance in the poem reveals to the dreamer the potential apotheosis of virtue and poetic achievement. This rather cursory listing serves only as a starting point for the following analysis. Each available interpretation reflects various possibilities presented by the vision and, when combined, they form an anamorphic composition that deconstructs the rote conventions and motifs that had persisted throughout the medieval period into something uncannily recognisable yet alien.

The terms Douglas uses to describe his vision have previously been addressed by Amsler where he notes that the opposed language used by the dreamer and narrator reveal their temporal distance. He argues, ‘the narrator’s invocation of God’s grace to help in describing the vision forces the reader to come to terms with the distinction between the dreamer’s perception of a “fanton” or “dreidfull terrour” (117) and the narrator’s present view of the dream as a true vision’.8 Although this distinction supports Amsler’s assessment of the temporal dissonance between dreamer and narrator more widely developed in the poem (an interpretation that is by no means nullified by the current analysis), it does seem to limit the dynamic nature of the vision to a linear progression rather than the layered chaos of possibilities that Douglas offers his audience.

Chaucer’s The House of Fame is an important intertext to Palyce. The Proem to Book I addresses the unstable and unreliable nature of dreams by listing their multivalent causes and sources. The narrator demurs that he could not presume ‘to knowe of hir signifiaunce […] Or why this more then that cause is’ (17, 20) and twice exclaims, ‘God turne us every drem to goode!’ (1; 58).9 Chaucer’s overview of the types of dreams – avision, revelacion, drem, sweven, fantome, oracle – immediately and overtly signals to his audience that his work participates in this unruly category of experience. In this way it differs greatly from Douglas’s interpretation of the literary dream vision, which organically mingles a litany of terms relating to the description of dream visions throughout the narrative. The apparently ad hoc nature of Douglas’s nomenclature contributes significantly to the character of the dream vision, since it does implicitly what Chaucer does in a rather heavy-handed way: it impedes the audience’s impulse towards categorisation as a means of interpretation.

This raises a key concern underpinning medieval critical thought on the subject of dreams, namely their status as reliable sources of knowledge. The wildly contradictory material pertaining to the interpretation of dreams, real or literary figment, might be reduced simply to the search for veracity. Douglas mobilises this epistemological concern as a pretence for defending the poetic process, thus intertwining a medieval issue with a humanist. At the close of the second part of the poem the dreamer is integrated into Calliope’s retinue after she comes to his defence against Venus’s indictment of the dreamer for blasphemy. Bearing witness to the divine harmony and perfection of Calliope’s company, the narrator interjects a defence of his recollection of events as well as the veracity of the dream. This dual defence exemplifies the (con)fusion of medieval and humanist modes of thinking characteristic of Douglas’s writing. Defending his project, the narrator attacks potential critics:

Eik gyf I wald this avyssyon endyte,

Janglaris suld it bakbyt and stand nane aw,

Cry ‘Out on dremes quhilkis ar not worth a myte.’

Sen thys til me all verité be kend,

I reput bettir thus till mak ane end

Than ocht til say that suld herars engreve.

On othir syd thocht thay me vilepend,

I considdir prudent folk will commend

The vereté and sic janglyng rapreve. (1267–75)

[Also, if I would indite this vision, idle-talkers would deride it and without fear cry, ‘away with dreams which are not worth a penny’. Since this is known to me to be all truth I consider it better to end here than to say anything that should upset listeners. On the opposing side though they despise me, I consider prudent folk will commend the truth and censure such fault-finding.]

Although the narrator attempts to pre-empt criticism, his simple declaration that his dream is true is problematic insofar as the narrator and the dreamer prove to be deeply unreliable voices, not least because the narrator repeatedly admits that he was out of his senses throughout much of the dream. Recollection and ‘lived’ experience are equally complicated by the interwoven narrative voices, which distort conventional narratorial boundaries. Consequently, the status of the dream as a reliable source of knowledge in general terms as well as the narrator’s recounting of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: the narrative grotesque

- Part I: The Palyce of Honour

- Part II: The Tretis of the Tua Mariit Wemen and the Wedo

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index