- 116 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Psychology

About this book

An introductory guide to the principal thoughts underlying present day experimental psychology for students. Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Psychology by Wilhelm Wundt, Rudolf Pintner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Psicologia applicata. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

AN

INTRODUCTION

TO PSYCHOLOGY

CHAPTER I

CONSCIOUSNESS AND ATTENTION

IF psychologists are asked, what the business of psychology is, they generally make some such answer as follows, if they belong to the empirical school: that this science has to investigate the facts of consciousness, its combinations and relations, so that it may ultimately discover the laws which govern these relations and combinations.

Now although this definition seems quite perfect, it is really to some extent a vicious circle. For if we ask further, what is this consciousness which psychology investigates? the answer will be, “It consists of the sum total of facts of which we are conscious.” In spite of this, our definition is the simplest, and therefore for the present it will be well for us to keep to it. All objects of experience have this peculiarity, namely, that we cannot really define them but only point to them, and if they are of a complex nature analyse them into their separate qualities. Such an analysis we call a description. We will therefore best be able to answer more accurately the question as to the nature of psychology by describing as exactly as possible all the separate qualities of that consciousness, the content of which psychological investigation has to deal with.

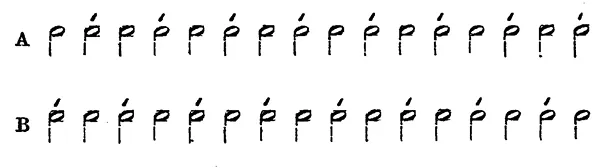

For this purpose let us make use of a little instrument to help us—an instrument well known to all who have studied music, i.e. the metronome. It is really nothing more than a clockwork with an upright standing pendulum, on which a sliding weight is attached, so that beats may follow each other at equal intervals in greater or less rapidity. If the weight is fixed at the upper end of the pendulum, the beats follow each other at an interval of two seconds; if at the lower end, the interval is shortened to about a third of a second. Between these limits every different length of beat can be produced. We can, however, increase these limits considerably by taking off the sliding weight altogether. Now the lower limit falls to a quarter of a second. Similarly we can obtain any longer time we choose with a sufficient degree of accuracy, if we have some one to help us. Instead of letting the pendulum swing of its own accord, the assistant moves it backwards and forwards with his hand, measuring off the longer interval fixed upon, by means of a watch, that marks the seconds. This instrument is not only very useful for teaching singing and music, but it is also a psychological apparatus of the simplest kind. In psychology, as we shall see, we can use it for so many purposes that we are almost justified in saying that with its help we can demonstrate the most important part of the psychology of consciousness. In order to be able to do this the instrument must satisfy one requirement, which every instrument does not possess. The strength of the beats must be sufficiently uniform, so that even to the most attentive listener differences in the intensity of the successive beats may not be noticed. To test an instrument in this respect, we proceed thus. We subjectively emphasise the one beat and then the other, as the two following rows of notes show:—

This diagram represents the separate beats by notes, and the accent shows those beats that are subjectively emphasised. Row A shows an ascending beat, and row B a descending one. Now if it happens that we can at will hear into the beats of the metronome an ascending or a descending beat (A or B), i.e. we can hear one and the same beat now emphasised and now unemphasised, then we may regard the instrument as suitable for all the psychological experiments to be described in the following pages.

Although the experiment described was only meant to serve as a test for the metronome, yet we can derive from it a remarkable psychological result. For we notice in this experiment that it is really extraordinarily difficult to hear the beats in absolutely the same intensity, or, to put it in other words, to hear unrhythmically. Again and again we recur to the ascending or descending beat. We can express this phenomenon in this sentence: Our consciousness is rhythmically disposed. The reason of this scarcely lies in a specific quality, peculiar to consciousness alone, but it clearly stands in the closest relationship to our whole psycho-physical organisation. Consciousness is rhythmically disposed, because the whole organism is rhythmically disposed. The movements of the heart, of breathing, of walking, take place rhythmically. In a normal state we certainly are not aware of the pulsations of the heart, but we do feel the movements of breathing, and they act upon us as very weak stimuli. Above all, the movements of walking form a very clear and recognisable background to our consciousness. Now our means of locomotion are in a certain sense natural pendulums, the movements of which generally follow with a certain regularity, as with the pendulum of the metronome. Therefore whenever we receive impressions in consciousness at similar stated intervals, we arrange them in a rhythmical form similar to that of our own outward movements. The special form of rhythm, ascending or descending, is within certain limits left to our own free choice, just as with the movements of locomotion, which may take the form of walking, of running, of jumping, and lastly of all different kinds of dances. Our consciousness is not a thing separated from our whole physical and mental being, but a collection of the contents that are most important for the mental side of this being.

We can obtain a further result from the experiment with the metronome described above, if we change the length of the ascending or descending row of beats. In our diagram each row, A and B, contains sixteen separate beats, or, taking one rise and fall together, eight double beats. If we listen attentively to a row of beats of this length when the metronome is going at a medium rapidity of, say, 1 to 1 1/2 seconds, and then after a short pause repeat a row of exactly the same length, we recognise immediately the identity of the two. In the same way a difference will be immediately noticed, if the second row is only by one beat longer or shorter than the first. It is immaterial whether we beat in ascending or descending rhythm. Now it is obvious that such an immediate recognition of the identity of two successive rows is only possible if each of them is in consciousness as a whole. It is not at all necessary for both of them to be in consciousness at the same time. We can see at once that consciousness must grasp them as wholes, if we consider for one moment an analogous case, e.g. the recognition of a complex visual image. If we look, for example, at a regular hexagon for a short time, and then cast another glance at the same figure, we recognise at once that both images are identical. Such a recognition is impossible if we divide the figure up into several parts and show these parts separately. Just as the two visual images appeared in consciousness as wholes, so must each of our rows of beats appear as a whole, if the second is to call up a similar impression to the first. The difference consists in this, that the hexagon was perceived in all its parts at once, whereas the beats followed each other in succession. Just because they follow in this way, such a row of beats possesses this advantage, that we can thereby determine precisely how far we can extend such a row so that it is still possible to grasp it in consciousness as a whole. It has been proved by such experiments that sixteen successive beats, alternately rising and falling, or so-called 2/8 time, is the maximum for such a row, in order that all the separate elements may still find room in our consciousness. We may therefore consider such a row as a measure for the scope of consciousness under these given conditions. At the same time it appears that this measure is, between certain limits, independent of the rapidity of succession of the beats. A grasping together of the row as a whole becomes, however, impossible, when the beats follow each other so slowly that no rhythm may be heard, or when the rapidity is so great that the 2/8 time is lost, and the mind tries to group the beats together in a more complicated rhythm. The former limit lies at about 2 1/2 seconds, and the latter at 1 second.

When we take the longest row of beats that can be grasped together as one whole in consciousness under the given conditions and call this the scope of consciousness, it is of course obvious that we do not mean by this expression the total content of consciousness that is present at one given moment. We mean only to denote the maximum scope of one single complex whole. Let us picture consciousness for a moment as a plane surface of a limited extension. Then our scope of consciousness is one diameter of this surface, and not the whole extent. There may at the same time be many other elements of consciousness scattered about beside the ones we are just measuring. They can, however, in general be left out of account, since in a case such as ours consciousness will be directed to the content that is being measured, and the elements outside of this will be unclear, fluctuating, and isolated.

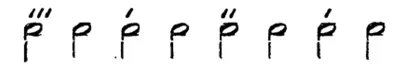

The scope of consciousness, in accordance with our definition, is a relatively constant value, if we keep to a special time, e.g. the 2/8 time. It does not change with a different rapidity of beat within the above-mentioned limits. A change in the time, however, exercises great influence. Such a change is to some extent dependent upon our will. We can hear into our uniform row of beats not only a simple 2/8 time, but a more complicated rhythm, e.g. the following 4/4 time:—

Such a row arises if we let different intensities of accent enter, say the strongest at the beginning of the row, a medium one in the middle, and a weak one in the middle of each of the two halves of the whole row, as in the diagram above. The strongest emphasis is denoted by three accents, the medium one by two, and the weak ones by one. This transition to more complicated rhythms is to a great degree dependent upon the rapidity of the beat, as well as upon our will. With long intervals it is very difficult to go beyond the simple 2/8 time. With short ones a certain exertion is necessary to withstand the impulse of transition to more complicated rhythms. When listening unconcernedly to the beats of the metronome when the interval between the beats is 1/2 second or less, the above-described 4/4 time generally appears. This groups together eight beats into one unity, whereas the 2/8 time only embraces two beats. Now if we measure the scope of consciousness for such a complicated row of beats, we find that five bars of 4/4 time can be grouped together and grasped as a whole; and if this row is repeated after a short interval, it can be recognised as identical with the preceding row. Here, then, we have forty beats as the scope of consciousness for this complicated rhythm, whereas with the most simple rhythmical arrangement we had only sixteen beats. This scope of forty seems to be the greatest we can attain by any means. We can, it is true, voluntarily call forth more complicated rhythmic arrangements, e.g. 6/4 time. But such an increase in the number of beats in the rhythmic arrangement demands a certain exertion, and the length of the row that can be grouped together as one whole does not increase, but decreases.

In these experiments a further remarkable quality of consciousness appears, which is closely connected to the rhythmical disposition of consciousness. The three degrees of emphasis, which the diagram of 4/4 time shows, form a maximum of differentiation which cannot be surpassed. Counting the unaccented beat as well, we arrive at a scale of intensity of four grades as the highest limit in the gradation of the intensity of impressions. This value clearly determines the rhythmical arrangement of the whole row, and with it the comprehension of this in consciousness, just as on the contrary the rhythm of the beats determines the number of gradations in intensity, which are necessary in the arrangement of the row of beats as supports for the comprehension by consciousness. Both factors therefore stand in close relationship to each other. The rhythmical disposition of consciousness demands certain limits for the number of grades of emphasis, and these on their part demand that specific rhythmical disposition which is peculiar to the human consciousness.

The more extensive the rows of beats become, which we join together in the experiments described, the more clearly does another important phenomenon of consciousness appear. If we pay attention to the relation between a beat, perceived in a certain given moment, and one that has immediately preceded it, and if we further compare this latter with a beat further back in the row that is being grouped together as a whole, differences of a certain kind between all these impressions appear. They are quite different from the variations in intensity and emphasis. To describe them we do best to make use of expressions, which were first of all formed in all languages to describe the perception of visual impressions, where the same differences also appear and are relatively independent of differences in the intensity of light. These expressions are “clearness” and “distinctness.” Their meanings almost coincide, but still they differ inasmuch as they denote different sides of the faculty of perception. “Clearness” refers more to the special constitution of the impression itself; “distinctness” to the relation of the impression to other impressions from which it seems to stand out. Let us transfer these conceptions in a generalised sense to the content of consciousness. One row of beats clearly shows in each of its separate elements the most varying degrees of clearness and distinctness. They all in a regular manner bear upon the beat that is affecting consciousness at the moment. This beat is the one that is most clear and most distinct. The ones immediately preceding are most like this one, whereas those that lie further back lose more and more in clearness. If the beat furthest away lies so far back that the impression has absolutely disappeared, then we speak in a picturesque way of a sinking beneath the threshold of consciousness. For the opposite process we have at once the picture of a rising above the threshold. In a similar sense for that gradual approach to the threshold of consciousness, which we notice in our experiments in the beats that lie further back, we use the expression “a darkening,” and for the reverse process “a brightening” of the content of consciousness. With the use of these expressions we can formulate in the following manner the condition necessary for the comprehension of a whole consisting of many parts, e.g. a row of beats: a comprehension as a whole is possible as long as no part sinks beneath the threshold of consciousness. For the most obvious differences in the clearness and distinctness of the content of consciousness, we generally use two other expressions, which, like our former ones of darkening and brightening, illustrate the meaning. We say that that element of consciousness, which is mostly clearly apprehended, lies in the fixation-point of consciousness, and that all the rest belongs to the field of consciousness. In our metronome experiments, therefore, the beat, that is at the moment affecting consciousness, lies in this subjective fixation-point,...

Table of contents

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

- CHAPTER I

- CHAPTER II

- CHAPTER III

- CHAPTER IV

- CHAPTER V