eBook - ePub

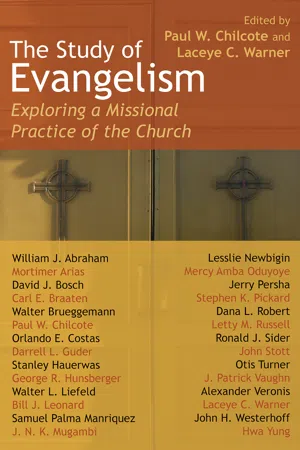

The Study of Evangelism

Exploring a Missional Practice of the Church

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Study of Evangelism

Exploring a Missional Practice of the Church

About this book

Christians and communities of faith today are rediscovering evangelism as an essential aspect of the church's mission. Many of the resulting books in the marketplace, however, have a hands-on orientation, often lacking serious theological engagement and reflection. Bucking that how-to trend,

The Study of Evangelism offers thirty groundbreaking essays that plumb the depths of the biblical and theological heritage of the church with reference to evangelistic practice. Helpfully organized into six categories, these broad, diverse writings lay a solid scholarly foundation for meaningful dialogue about the church's practice of evangelism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Study of Evangelism by Paul W. Chilcote, Laceye C. Warner, Paul W. Chilcote,Laceye C. Warner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Defining the Ecclesial Practice and Theology of Evangelism

The essays collected in this opening section inform much of the recent discussion about definition, methodology, and practice as it relates to the ministry of evangelism. Church leaders of every stripe have spilled much ink over these particular issues during the past half-century and have conducted local and global gatherings to engage the Christian community in discussion around them. The contemporary climate of mainline denominational decline and general malaise in North America clamors for the careful definition of evangelism and the construction of a coherent theology of this ecclesial practice. While an increasing number of practitioners flood the market with practical guidebooks for evangelistic practice or panhandle their own particular version of evangelism, rarely do these books afford a theologically and historically robust understanding of evangelism or evaluate its practice from a critical point of view. In the world of the academy, scholars have attempted to find a niche for evangelism, some setting it apart as an aspect of missiology or a crucial topic within ecclesiology in the theological curriculum, others viewing it as a sub-discipline of practical theology or as a discrete field in its own right. In the context of this ferment, the writers featured here help to refine our understanding of the nature, purpose, and function of evangelism within the larger missio Dei.

This volume opens, therefore, with questions of definition and theological vision. Both terms, “evangelism” and “mission,” elude easy definition. Difficulties also surround any attempt to articulate the interface of these two distinct ministries in the life of the church. Conceptual boundaries shift as interest groups labor to claim sufficient space for agendas that begin more often than not from reactive starting points rather than constructive biblical and theological foundations. Whether originating in the twentieth-century Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy in the United States or related to the legacy of colonial imperialism in an African context, to illustrate with just two examples, polarities are often manifest in conversations about the meaning of evangelism. The essays in this section, representing diverse international but biblically grounded perspectives, provide fundamental insights for the purpose of mapping this varied and, at times, treacherous conceptual terrain.

At least two main themes pervade the following essays: (1) the need to articulate the relationship between evangelism and mission, and (2) the dual dynamic of personal salvation in Jesus Christ and social action related to the reign of God in the practice of evangelism.

David J. Bosch, former dean of the Faculty of Theology at the University of South Africa in Pretoria, demonstrates how scholars and practitioners articulate a wide range of meaning in their efforts to define evangelism and mission. In a masterful survey of the literature, he identifies six ways in which these terms are used as synonyms and four ways in which they are conceived as distinct realities. In an effort to redefine evangelism, he argues for mission as the wider and evangelism as the narrower concept. A biblical understanding of mission, in his view, involves the believer in a drama of cosmic redemption and the glorification of God. Evangelism aims at incorporating others into this vision by means of witness, invitation, and communal outreach, through risk-taking practices that offer salvation as a gift and enlist Christians into the service of God’s comprehensive reign. While distinct but not separate from mission, “evangelism is the core, heart, or center”of it all.

William J. Abraham and Orlando E. Costas address the second theme — the unfortunate bifurcation of personal salvation and social action in many theologies of evangelism. In opposition to truncated theologies of this variety, Abraham — an Irish Methodist converted in young adulthood, at once a theologian, philosopher, and evangelist — argues for a robust ecclesiology to frame the church’s ministry of evangelism. As in his classic study, The Logic of Evangelism, over against reductionist tendencies that view evangelism (in more “conservative” circles) simply as proclamation, or simply as ministries of justice (in more “liberal” traditions), he describes evangelism as “a polymorphous ministry aimed at initiating people into the kingdom of God.” As a dynamic process, evangelism entails not only invitation into God’s reign, but also catechesis, or instruction, that grounds the believer in a life devoted to God’s vision for all humanity.

In similar fashion, Orlando Costas, a Puerto Rican evangelical who taught missiology and evangelization in both North and Central American settings, proclaims a holistic vision of mission and evangelism based upon a “gospel of salvation” rooted in the biblical text. According to Costas, the particularity of Christianity’s history in the Latin American context presents a severely conflicted narrative characterized by colonialism and oppression. This history leaves many suspicious of the church’s relevance for the contemporary context. For Costas, a biblical doctrine of salvation reveals a liberating and searching God. Evangelism involves testimony to the reality of the life of Jesus of Nazareth and affirmation of the truth with regard to his redemptive mission and the ultimate reality of God’s way. This witness, however, only becomes meaningful as it relates to the struggles for economic justice, dignity, solidarity, and hope within concrete human communities. The gospel of salvation is both gift and demand, calling for relationships built on trust and actions that manifest God’s rule over all aspects of life.

At the dawn of the new millennium, societies dominated by secularization, particularly in the Western hemisphere, pose one of the greatest challenges to Christianity. In the closing article, Lesslie Newbigin, one of the greatest ecumenical statesmen and missionary theologians of the twentieth century, tackles this complex issue. Despite the fact that many Christians hailed the rise of secularization as a positive development, the ultimate consequence has been a shift from secular to pagan societies in which “faithless” people give their allegiance to “no-gods.” Newbigin argues that the presence of the new reality of God’s reign, as alternative to the domestication of the gospel, manifests itself in a peculiar shared life, the actions that originate it, and words that explain it. Evangelism, in such a context, has little to do with increasing the size and importance of the church. Rather, the clue to evangelism in a secular society is the local congregation, the way these communities shape their members as agents of God’s reign and equip them to explain the Christian story through word and deed in a compelling and winsome manner.

From varied perspectives around the world, these writers develop definitions and build theologies of evangelism that refuse the old dichotomies separating mission from evangelism — the gift of personal salvation from the call to live in and for God’s just and peaceable rule. They demonstrate how this holistic vision shapes both the ecclesial practice and the theology of evangelism. While evangelism and mission are distinct concepts, they are inseparable. In short, evangelism emerges as a complex set of formational practices at the heart of God’s mission for the church in the world.

CHAPTER 1

Evangelism: Theological Currents and Cross-Currents Today

David J. Bosch

My assignment is to provide a concise survey of the ways in which evangelism is being understood and practiced today. I assume that this does not preclude an attempt to give my own view on what I believe evangelism should be. One of the problems is that evangelism is understood differently by different people. Another problem is that of terminology. The older term, still dominant in mainline churches, is “evangelism.” More recently, however, both evangelicals and Roman Catholics have begun to give preference to the term “evangelization.” It does not follow that they give the same contents to the term, as I shall illustrate.

Yet another problem is that of the relationship between the terms “evangelism” and “mission.” Perhaps the best way of attempting to clear the cobwebs is to begin by distinguishing between those who regard evangelism and mission as synonyms and those who believe that the two words refer to different realities.

Mission and Evangelism as Synonyms

It is probably true that most people use “mission” and “evangelism” more or less as synonyms. Those who do this do not necessarily agree on what mission/evangelism means. Perhaps one could say that the definitions of mission/evangelism range from a narrow evangelical position to a more or less broad ecumenical one.

Position 1: Mission/evangelism refers to the church’s ministry of winning souls for eternity, saving them from eternal damnation. Some years ago a South African evangelist, Reinhard Bonnke, wrote a book with the title Plundering Hell. This is what the church’s mission is all about: making sure that as many people as possible get “saved” from eternal damnation and go to heaven. According to this first position it would be a betrayal of the church’s mission to get involved in any other activities. Most people subscribing to this view would be premillennialist in their theology. Typical of the spirit of premillennialism is Dwight L. Moody’s most quoted statement from his sermons: “I look upon this world as a wrecked vessel. God has given me a lifeboat and said to me, ‘Moody, save all you can.’”1

Position 2: This position is slightly “softer” than the first. It also narrows mission/evangelism down to soul-winning. It would concede, nevertheless, that it would be good — at least in theory — to be involved in some other good activities at the same time, activities such as relief work and education. On the whole, however, such activities tend to distract from mission as soul-winning. It should therefore not be encouraged. Involvement in society is, in any case, optional.

Position 3: Here also mission/evangelism is defined as soul-winning. However, in this view, service ministries (education, health care, social uplift) are important, since they may draw people to Christ. They may function as forerunners of, and aids to, mission. “Service is a means to an end. As long as service makes it possible to confront men with the gospel, it is useful.”2

Position 4: Here mission/evangelism relates to other Christian activities in the way that seed relates to fruit. We first have to change individuals by means of the verbal proclamation of the gospel. Once they have accepted Christ as Savior, they will be transformed and become involved in society as a matter of course. In the words of Elton Trueblood, “The call to become fishers of men precedes the call to wash one another’s feet.”3 Jesus did not come into the world to change the social order: that is part of the result of his coming. In similar fashion the church is not called to change the social order: redeemed individuals will do that.

Position 5: Mission and evangelism are indeed synonyms, but this task entails much more than just the proclamation of the gospel of eternal salvation. It involves the total Christian ministry to the world outside the church. This is, more or less, the traditional position in ecumenical circles. When the International Missionary Council merged with the World Council of Churches (WCC) at its New Delhi meeting in 1961, it became one of several divisions of the WCC and was renamed Commission on World Mission and Evangelism. Both words, “mission” and “evangelism,” were thus included in the title, not because they meant different things but precisely because they were, by and large, understood to be synonyms. Another synonym was the word “witness,” which is also often used in the New Delhi Report. Phillip Potter was correct when he wrote, in 1968, that “ecumenical literature since Amsterdam (1948) has used ‘mission,’ ‘witness’ and ‘evangelism’ interchangeably.”4 This task was classically formulated as the ministry of the “whole church taking the whole gospel to the whole world.” This ministry would, in the classical ecumenical position, always include a call to conversion.

Position 6: This goes beyond the previous position in that it does not insist that mission/evangelism would under all circumstances include a call to repentance and faith in Christ. Gibson Winter, for instance, says, “Why are men not simply called to be human in their historical obligations, for this is man’s true end and his salvation.”5 Here mission/evangelism is understood virtually exclusively in interhuman and this-worldly categories. In similar vein George V. Pixley defines the kingdom of God exclusively as a historical category. The Palestinian Jesus movement, which was, according to him, a wholly political movement, was completely misunderstood by Paul, John, and others, who spiritualized Jesus’ political program.6 In Pixley’s thinking, then, salvation becomes entirely this-worldly, God’s kingdom a political program, history one-dimensional, and mission/evangelism a project to change the structures of society.

Evangelism Distinguished from Mission

There are four ways in which evangelism and mission are distinguished from each other as referring to different realities:

1. The “objects” of mission and evangelism are different. In the view of Johannes Verkuyl, for instance, evangelism has to do with the communication of the Christian faith in Western society, while mission means communicating the gospel in the third world.7 Evangelism has to do with those who are no longer Christians or who are nominal Christians. It refers to the calling back to Christ of those who have become estranged from the church. Mission, on the other hand, means calling to faith those who have always been strangers to the gospel. It refers to those who are not yet Christians.

This view is still generally held in continental European circles, in both Lutheran and Reformed churches. It is, in fact, also the traditional view in Roman Catholicism, even in Vatican II documents such as the Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium) and the Decree on Mission (Ad Gentes).

2. A second group of theologians, instead of distinguishing between evangelism and mission, have decided simply to drop the word “mission” from their vocabulary. The French Catholic theologian Claude Geffré prefers “evangelization” to “mission” because of the latter term’s “territorial connotation … and its historical link with the process of colonization.”8 Other Roman Catholics appear to move in a similar direction. John Walsh, in his book Evangelization and Justice, calls everything the church is doing in the areas of “human development, liberation, justice and peace … integral parts of the ministry of evangelization.”9 In similar vein Segundo Galilea recently published a book in which the activities described in the Beatitudes of the Gospels of Luke and Matthew are designated “evangelism”: The Beatitudes: To Evangelize as Jesus Did.10 Once more a very comprehensive, almost all-embracing understanding of evangelism comes to the fore and the concept “mission” is dropped.

3. A third group of theologians offer a variation of the position just described. They hold onto both concepts, “mission” and “evangelism”; however, the way they do it is to regard “evangelism” as the wider term and “mission” as the narrower term. Evangelism is described as an umbrella conce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Defining the Ecclesial Practice and Theology of Evangelism

- Part Two: Biblical and Historical Sources for the Study of Evangelism

- Part Three: The Study of Evangelism in the World of Theology

- Part Four: The Study of Evangelism Among the Ecclesial Practices

- Part Five: Evangelism in Diverse Ecclesiastical and Ecumenical Settings

- Part Six: Evangelistic Praxis in Diverse Cultural Contexts

- Afterword: Continuing Conversations and New Trajectories in the Study of Evangelism

- Further Reading