- 434 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The twenty-one contributions to About: Designing draw on a rich variety of methodological positions, research backgrounds and design disciplines including architecture, product design, engineering, applied linguistics, communication studies, cognitive psychology, and discourse studies. Collectively these studies comprise a state-of-the-art overview

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access About Designing by Janet McDonnell,Peter Lloyd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Health & Safety. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Several years ago, and in conversations with fellow academics from the international community of design thinking researchers, we began to formulate the idea of providing a way of facilitating research collaboration and communication through sharing a common research dataset. We would invite internationally leading researchers to make use of the same dataset, share their findings with each other and at a workshop, subject their work to critical scrutiny by peers who were familiar with the same dataset, and produce a book from the results. The idea of distributing a dataset for analysis by researchers interested in design thinking had proved very successful in 1994 when Nigel Cross, Kees Dorst, and Henri Christiaans filmed designers at Xerox PARC to gather recordings of design problem solving behaviour in a laboratory setting. This data was distributed for wider analysis to test the potential (and limitations) of protocol analysis1. Indeed, the findings from that project, presented in the Delft protocols workshop, remain something of a landmark in design thinking research and we felt the time was right, 10 years on, to try and match this achievement by revisiting the shared data approach. Our conversations struck a chord, and this book is one of the outcomes of the project which has unfolded.

1 HOW THIS BOOK CAME ABOUT

In the 10 years since the Delft workshop and the start of our project the nature of design thinking research had also begun to change. Increasingly, studies were concentrating on designing in more naturalistic settings, if not wholly in design practice, and the scope of what was regarded as design activity broadened. The social aspects of design thinking were being emphasised; one trend was towards paying attention to the way that designing occurs between people trying to reach a common goal, rather than on individual design problem solving that can be studied in a lab-experiment. A richer, more contextual, understanding of design thinking was beginning to emerge; an understanding that shifted the imperative towards studying naturally occurring design activity in authentic settings. The common dataset on which the chapters in this book are based comprises material from real design meetings which form part of the routine practices of professional designers.

In 1994 the workshop had centred around a common method – protocol analysis – as well as a common dataset, but in recent years a wider variety of research methods have been used in response to our developing understanding of design thinking. Some methods are drawn from the social sciences and others finesse methods used previously in design thinking research. Some examples of the wide variety of approaches used to look at designing in context are: interaction analysis2, computational linguistics3, viewpoint methodologies4, semiotics5,6, ethnography7,8, functional linguistics9, cognitive ethnography10, and discourse analysis11,12. Additionally, many research disciplines aside from those primarily interested in design thinking have addressed the recording and analysis of professional practice. This has led to the development and application of methodologies which are equally appropriate for studying design practitioners and design practice. Relevant examples include work drawn from sociology13, ethnomethodology14, communication studies15, naturalistic decision making16, and social theories of learning17; and there are many others.

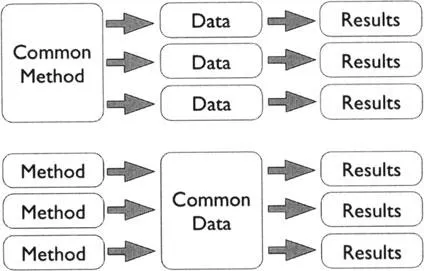

This plurality of methodologies presented a problem: how can common data support analyses which use different methodologies? Surely the focus of research enquiry comes first, then one selects an appropriate methodology and collects data in a certain way to meet the demands of the research, rather than starting with data and applying a methodology? Weren’t we putting the cart before the horse? What we proposed is summarised in Figure 1 where it is contrasted with the procedure which is common in established subject disciplines where certain methods are unambiguously specified and are privileged, for example randomised controlled trials in some branches of medicine. Conventionally, scientific and social-scientific studies are carried out independently of one another but with a common methodology, leading to data being collected, analysed, and then results published. In some fields like experimental psychology, for example, there is broad agreement about what constitute legitimate research methods and what assumptions underlie them, providing at least some common basis for supporting discussion about findings and their validity.

Design thinking research and its research community has grown in a different way through contributions from researchers from different disciplines and fields. The contributors to this book, for example, include researchers with backgrounds in psychology, sociology, linguistics, philosophy, education, architecture, industrial and product design and a whole range of engineering disciplines. What became evident was that the research project that resulted in this book would keep the data constant, while accepting that methods would be various. This would mean that discussion about research findings would inevitably also invite and support discussion about method. The chapters in this book are intended to provoke methodological questions: if the authors make claims from the data, how does the research method they have used ensure their findings are valid and what means do they use to be convincing? Our hope is that as you read the chapters you will find it is instructive to compare methodologies, especially where different contributions focus on the same segments of data. We have tried to illustrate the potential for comparison that a common dataset can offer in Section 4 later in this introductory chapter.

Our interest was in providing a common dataset of material drawn from design activity taking place in natural settings. The collection of data from authentic professional design activity does present a number of problems however. There are confidentiality issues associated with products that are close to market. There is the timing and fragmented nature of real-world design processes which have hold-ups and delays, and periods of intensive, urgent activity, all for very good reasons. There is the limited ability of a researcher to ‘be there’ when significant activity takes place. There are also ethical concerns about obtaining permission to use recorded data for researchers at different institutions internationally.

The main problem, however, is in deciding what data to capture. The nature of design in practice means that even small projects take place in many different environments among a shifting set of participants. Designing occurs in many, of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- Part 1: Understanding Design Processes

- Part 2: Values in Designing

- Part 3: Aspects of Design Cognition

- Part 4: Design Process Models

- Part 5: Language, Discourse and Gesture

- Part 6: Constructing Roles

- Part 7: Objects, References, Context

- List of Contributors

- Author Index