![]()

1

Discourse and Diegesis

Although comics is a visual art form and comics theory has developed from multiple disciplines, comics scholarship has been largely literarily and narratively focused, a tendency Kukkonen justifies by defining “literature” as “not tied to the written text,” since “films can be seen as literature, too” (2013: 2). Even if comics are literary in an expansive sense, the categorical inclusion does not dictate literary methods of analysis. Medley correctly identifies a need “to balance out these literary approaches” (2010: 55), and García warns against “the analytical tendency that makes use of tools proper to narratology,” in order to “focus our attention instead on visual and material features” (2010: 4). Miodrag similarly argues “that the practices and methodologies of art criticism are as valuable to the study of comics as the ‘literary’ readings of theme and narrative that have to some extent dominated critical approaches to the form” (2013: 199).

Many approaches to studying images begin with object-based formal analysis in the tradition established by art historians in the late 1800s: identifying elements of line, shape, light value, space, color, texture, and pattern, as well as such design principles as unity, balance, emphasis, proportion, and implied movement. Iconographic (literally “written image”) analysis focuses on subject matter, including the traditions of signs and symbols identified by Panofsky in the mid-twentieth century. Other visual approaches analyze style, historical and cultural context, viewers’ perceptual responses, and the history of an image’s public reception. Since works in the comics form are a subcategory of the visual arts, all of these approaches are applicable and likely essential to comics analysis. My focus is formal, so reception, cultural context, and iconographic traditions are beyond the scope of this book. While design principles and other elements of visual analysis are essential, I have nothing to add to their theory. Despite García’s warning, I do use literary tools, but my focus is not on the narrative qualities that sequenced images may produce, but on the image features that may produce them.

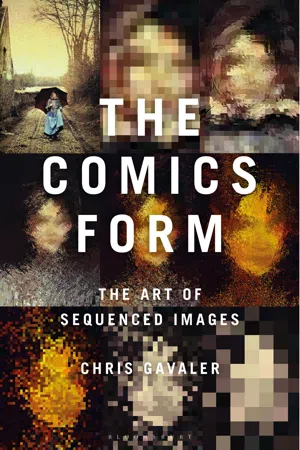

As detailed in the Introduction, The Comics Form explores the two most common formal features identified in scholarly definitions: images and sequence. Sequence requires juxtaposition (and possibly nothing else), which I begin to discuss in the third chapter. This chapter and the next focus on the qualities of a comics image. “Image” is an imperfect term because it can be used synonymously with “representation,” meaning a simulation of something else. I therefore divide images into two categories: non-representational images are only their physical features; representational images are also understood in relation to what they represent. Adapting terms from literary criticism, these two sets of qualities are diegeses and discourses. A representational image is both the subject matter simulated (diegesis) and the physical substance that simulates (discourse). More simply, a representational image has both form and content, while a non-representational image has form only.

1. Formal Qualities

What are the formal features of an image in the comics form?

I derive “images” from scholarly consensus, but while all scholars understand comics to include them, few specify a meaning. Though “image” can be used to describe multiple senses, when used to describe works that have been called “comics,” the term appears to refer to visual images only, ignoring non-visual qualities highlighted by Hague in his accurate description of comics scholarship as ocularcentric. Cohn and Cook also include “visual” and “visually” in their comics definitions (2013: 1–2; 2015: n.p.). Kwa identifies “most significantly, the emphasis on an insistently two-dimensional surface” (2020: xxii). Bateman identifies two qualities, “two-dimensional and static,” when stipulating the nature of image-texts (2014: 28), which include most works in the comics medium (defined in the Introduction as works published by an entity that identifies as a comics publisher). “Comics image” then might mean: any visual flat static image juxtaposed with another.

If we accept that inferred definition, works in the comics form do not include three-dimensional art. I suspect most readers would agree that a sculpture garden is not a comic—even when sculptures share prominent features with comics. Siegfried Neuenhausen’s 1980 Small Sequence consists of five, reproducible bronze statuettes representing a figure dressed in a hat and trench coat who appears to be incrementally sinking from knees to chin into whatever surface the statuettes are resting on. So not only are the statuettes juxtaposed images, they create the impression of a single character repeated in multiple instances that must be viewed in a specific order to experience a unified event. Recurrence and sequence are common qualities discussed later, but despite its possessing such qualities, it seems reasonable to exclude Small Sequence only because it is three-dimensional. Similarly, although Nahoko Kojima’s 2012 Cloud Leopard, Swimming Polar Bear, and Washi (a bald eagle) are made of paper (the most common comics-medium material), they are suspended from wires to create three-dimensional shapes and so are presumably not comics, despite being juxtaposed images in a thematically unified series. While it’s possible to imagine something that could be called a “three-dimensional comic” (perhaps a sequence of dioramas featuring a set of characters that continues an existing comics-medium story), the three-dimensional comic would not be in the comics form.

“Flat” still produces challenges since it is unclear when an object should be considered two- or three-dimensional. Is Lorenzo Ghiberti’s 1452 Gates of Paradise—which consists of two, five-paneled, bronze doors, containing Old Testament scenes in bas-relief (literally “low raises”)—in the comics form? At what point does the discursive depth of an image become definingly three-dimensional? US quarters include bas-relief portraits of George Washington, but their depth is shallower than what a painter employing an impasto technique—as Van Gogh does in his 1890 Still Life: Vase with Pink Roses—can produce with layers of oil paint. Technically, any painting or even pencil drawing is three-dimensional. Despite this ambiguous threshold, I accept “flat” as a quality of images in the comics form.

“Static” distinguishes a comic from a film—or at least a projected film. If a film is the celluloid strip of still images that is run through a projector, the strip is a sequence of static images. Even so, the strip not the projection of moving images would formally be a comic. Webcomics offer a further challenge since some include segments of animation. Though segments of webcomics with animation are not in the comics form, if a webcomic contains sequenced static images at least those portions can be analyzed formally as a comic. Conversely, some projected films contain static images—or multiple identical images projected to appear static. Chris Marker’s 1962 La Jetée consists (almost) entirely of projected stills and so would be in the comics form. Andy Warhol’s 1966 Chelsea Girls, which features a split screen and so juxtaposed moving images, would not be.

A comics image could include other physical constraints. Kwa assumes a “small format” (2020: xxii). The image might be hand-held and so include both traditionally printed comics and webcomics viewed on a phone, but not framed artboards displayed on a gallery wall. Dividing points could be arbitrary, ambiguous, or both. A laptop is not typically hand-held but can be, while an 80s-era PC cannot, yet both can be used to view a comic on similarly sized screens. Likely any size constraint would eliminate the Nazca Lines, a set of geoglyphs carved in a southern Peru desert roughly two thousand years ago, since some of the images are more than a half mile wide and combined cover 19 square miles. However, the Nazca Lines, which include representations of a dog, whale, spider, hummingbird, and monkey in relatively close proximity, are not formally different from a page of identically drawn and proportionately spaced images. At the opposite extreme, quantum dot technology produces inkjet-printed images the width of human hair and viewable only through microscopes. While excluding such extremes may seem intuitively self-evident, the adjective “small” lacks both clear parameters and formal justification while also adding little to analysis.

Publishing-based definitions require a comics image to be reproduced. If so, artboards used during the printing process are not themselves comics. Comics as defined by their history of publication do not have single originals. Every 1962 copy of Amazing Fantasy #15’s first run is equally the original comic, but Steve Ditko’s Amazing Fantasy #15 art housed in the Library of Congress is instead material for manufacturing a comic, which did not include the blotches of white-out and blue guidelines that are elements of the artboards only. The adjective “reproduced” formally distinguishes a work in the comics medium from its artboards, but then the definition applied formally includes all types of reproduction. A PowerPoint projection of a comic scanned into a digital pdf would be a comic, even though the projection is made of light and exists only while projected. If the pdf is printed from a photocopier, its pages of toner-formed images would also be a comic. Meskin explores the issue of multiplicity in greater detail, concluding: “An exact duplicate of a comic does not count as authentic unless it was mechanically copied from the original plate or art or some other genuine copy” (2014: 41). Attempts to distinguish “authentic” and “genuine” comics reveal the publishing-focused impetus for the stipulation, especially since an “exact duplicate” would be physically indistinguishable from its source. Meskin also ignores “the production, transmission and consumption of unauthorized comic book scans” through a digital culture network involving weekly titles that numbered 28,000 in 2010 (Wershler, Sinervo, and Tien 2013). Regardless, concerns for authenticity and reproduction technologies seem specific to the comics medium, and so I do not adopt “reproduced” or any further stipulated variant as a necessary quality of an image in the comics form.

Other formal requirements are possible. Groensteen and Grennan might include the adjective “drawn,” since Groensteen’s monstrator is responsible for “putting into drawing” (2010: 4), and Grennan’s book-length study is A Theory of Narrative Drawing (2017). “Drawn,” however, would arbitrarily eliminate photographic images and so photocomics, including Italian fumetto, as well as other images produced by creative processes that are not strictly drawing-based. Cook might eliminate La Jetée from the comics form because his comics definition requires that the “audience is able to control the pace” (2015). Kwa refers similarly to “the invitation to keep looking” (2020: xxii). The stipulation would separate La Jetée from the comics medium, but audience-controlled pace introduces other ambiguities: What if a viewer is watching a film while intermittently pressing pause? Audiences also control pace when viewing galleries and photo albums.

Rather than adopting additional formal parameters in an attempt to exclude works outside the comics medium, I accept the results of the broad formal net. Despite their significant differences, La Jetée, Nazca Lines, and many works in the comics medium share a meaningful set of formal features. Because that set is otherwise unnamed, I call it “the comics form,” and I understand an image in the comics form to mean any flat, static, visual image juxtaposed with another, leaving “small,” “reproduced,” “drawn,” and other descriptors as common but formally non-essential conventions of the comics medium.

2. Content and Form

Though a work in the comics form includes at minimum a set of the above physical qualities, it often involves something more.

From the Greek word for narrative, “diegesis”—and the adjective “diegetic”—may refer to a story, the elements that comprise a story (including such things as settings, events, actions, characters, and characters’ internal experiences), or the larger world in which a story takes place. Since a single representational image may or may not be understood as being, telling, or referring to a story, I understand diegesis to include represented subject matter generally. This visual application is an expansion of diegesis in the literary and narratological sense and may include an entire world represented but only partially pictured. If the image is Kehinde Wiley’s 2018 portrait of Barack Obama, its world is understood to be our world. If the image is a still from Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis, the diegetic world is fictional and therefore a different world. If the image is Frida Kahlo’s 1946 The Wounded Deer, a self-portrait featuring the artist’s head attached to a deer’s body, the relationship of the image to our or any other world may be unclear. Regardless, diegesis can be understood generally as all represented content, overt and implied.

“Discourse”—and the adjective “discursive”—refer to an image as a physical object independent of anything it might represent. The discourse of a work in the comics form includes the physical qualities identified in the previous section. In literary approaches, “discourse” may be used to mean or relate to things such as plot, syntax, and other non-physical qualities excluded here, though this stipulated meaning can be applied to a prose-only work, too, “understood in terms of its purely physical properties” (Goldberg and Gavale...