![]()

1

Cordoba, the frontier, and the Inquisition, 1450–87

‘High-ranking people, good, God-fearing Christians’1

Competing visions for Christianizing Iberia

The process of Christianizing Iberia did not start or end with the Catholic Monarchs, but it was in their reign that the conquest of Granada and the expulsion of the Jews gave it increased momentum. Medieval Spain had had the largest population of Jews in Europe but, by the early fifteenth century, most had undergone baptism following a wave of violence against them. The pogroms had started in Holy Week 1391, in Seville where, incited by a hate preacher named Ferrán Martínez, the populace rose up against the Jewish community in a frenzy of slaughter and robbery which, two days later, was replicated in Cordoba and then spread to other towns and cities across Castile and Aragon.2 A sixteenth-century account claimed that four thousand Jews perished in Seville alone and that, when King Enrique III later visited, ‘almost all the Jews of that city had become Christian and in Cordoba and Toledo they did the same.’3 The ‘flood of baptisms’, spurred on by an intense programme of proselytization led by Vincent Ferrer (1350–1419) and increasingly repressive measures against those who were unwilling to convert, sowed the seeds for the ‘converso problem’ which emerged a generation later.4 For the converts, becoming a ‘new Christian’ offered paths to social advancement which had previously been closed, but for existing Christians – now redefined as ‘natural’ or ‘old’ Christians – it meant having to share their privileges with a previously inferior social group whose conversion everyone knew had been coercive. These circumstances forced a reconsideration of the whole nature of Christian society from which, during the fifteenth century, two competing visions emerged. On the one hand, there arose an exclusionary ideology which sought to give old Christians precedence over the newly converted by limiting the latter’s participation in civil society and, on the other, a theological position contending that the Christian church was a unity in which there were no distinctions between people of different races or origins and that Jewish people, as all others, were able to redeem themselves through baptism and divine grace.

As the rigid medieval distinctions between faiths became blurred, there was a turn to genealogy rather than confessional status as a way of expressing identity and difference.5 During the reign of Enrique IV (1454–74), Alonso de Espina (1412–91) popularized the thinking of thirteenth-century theologian Duns Scotus, preaching and writing that Christian society had to be purified by rooting out the enemies of the faith, who he identified as Jews, Moors, demons and heretics.6 Instead of being welcomed in, converted Jews were increasingly treated as suspect members of Christian society, if not as outright heretics. When, in the mid-fifteenth century, these ideas started to find expression in prejudice and violence against converts, leading converso intellectuals were motivated to develop the theological basis for the alternative, integrative position. Alonso de Cartagena’s Defensorium Unitatis Christianae (1449–50) provided an arsenal of scriptural references to be drawn on later by those seeking to legitimize converso status within Catholic society and argue more widely for tolerance within the church. He drew particularly on the epistles of St Paul – a convert from Judaism par excellence – and argued not only that converted Jews could be as good Christians as old ones, but also that they had a primary role in God’s plan for the redemption of the world. He contended that the sacrament of Baptism created a single Christian body and that any attempt to create division and distinction within it was therefore itself a heresy, bringing the extent of Christ’s mercy into question.7 In a similar vein to Cartagena, Alonso de Oropesa’s Lumen ad revelationem gentium (begun in 1450, completed by 1465) reflected on the transformative role of Jewish conversos in creating spiritual unity within the church.8 Oropesa argued that the union of former Jews with old Christians had moved the church on from the servitude of the ‘Old’ Law to the liberty of the ‘New’, one in which all its members were linked by their faith and through the spiritual power of the Eucharist in a single body in a perfect state of grace. Judaism and Christianity were not seen as opposed, but rather the former was a precondition for the latter, which was a ‘perfection’ of it. Oropesa, who was a Jeronymite monk and head of the Order from 1457, made a strong point about the dangers for humankind of neglecting to cultivate friendship and fellowship, stressing the importance of Christians living in peace and harmony with each other and citing St Paul on the prime virtue of charity above faith and hope.9 These men are seen as the precursors of Erasmianism in Spain and an inspiration for the more compassionate positions in relation to the treatment of the native inhabitants of the New World as well as later spiritual movements arising in sixteenth-century Spain.10 Juan de Torquemada (1388–1468), writing in response to the same events, made the Eucharist even more significant in forging unity between Christians and former Jews, arguing that Christians of all origins consume Jewish flesh and blood through the transubstantiation of the bread and wine, since Jesus was Jewish.11 These egalitarian principles and the idea that virtue and nobility are independent of lineage were taken up and widely disseminated in humanist literature and poetry.12

Image 3 La Fuente de la Gracia by Jan van Eyck. This painting is believed to have been commissioned by Alonso de Cartagena in the mid-1440s to illustrate the arguments he makes in his Defensorium Unitatis Christianae: the importance of the peaceful conversion of Jews in the salvation story and the extension of God’s grace to all.13 © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Cordoban conversos

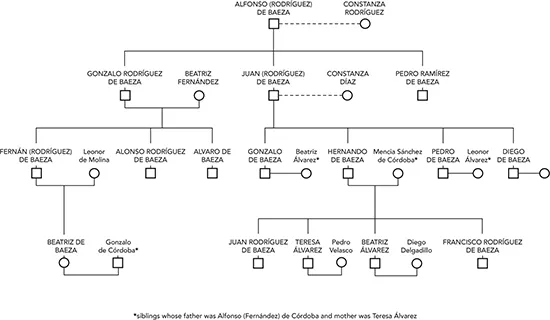

It is most likely that members of Hernando de Baeza’s family were among those Jews who converted in the aftermath of the pogroms of 1391 since his father and, as far as we can tell, his grandfather were, at least nominally, Christian. The label ‘converso’ might suggest a recent, individual decision to adopt Christianity; in fact, it would have been several generations since members of Hernando de Baeza’s family had been living as Jews. By the time he was born – probably around 1455 – his family had become deeply embedded in the political and economic life of Cordoba – the second city in Christian Andalusia after Seville. It was an industrious city with well-regulated trades such as leather, metalworking and textiles.14 A huge variety of foods and primary materials such as dyestuffs and seeds arrived in the city via the Guadalquivir River or by land at one of its four gates. One of Hernando’s uncles, Pedro Ramírez de Baeza, held the tenancy of the Casa de la Aduana or Customs House; another uncle was the Town Clerk (escribano mayor) and his father, Juan de Baeza, was the council’s financial administrator (mayordomo de los propios).15

His family’s circumstances are a close fit with the remarkably consistent descriptions of contemporary chroniclers of the rise of the conversos in the urban centres of Andalusia during this time. Writing post-hoc, to explain the need for the Inquisition, chroniclers describe them ‘enriching themselves by dubious means’, using public positions for their own benefit, obtaining royal favours, and intermingling with the nobility.16 A witness in a later limpieza de sangre hearing remembered the Baezas as: ‘high ranking people, good God-fearing Christians who were highly regarded by the Lords of Aguilar, in the best positions and related to the most high-ranking and richest people in Cordoba’.17 As a witness nominated by the individual under scrutiny she would have certainly understood the importance of her testimony but, nonetheless, the evidence largely supports her assertion.

Image 4 The family of Hernando de Baeza – genealogical chart. © Teresa Tinsley.

Hernando’s father, Juan de Baeza and uncle Pedro are described in archive documents as criados of the powerful Fernández de Córdoba family – Lords of Aguilar – which dominated Cordoba during this period. Although the word literally meant someone living and brought up in a noble household, by the period under consideration, the term was used more generally to cover a very wide range of circumstances, from menial domestic service to roles which required a high level of responsibility and skill, such as the command of a fortress.18 At what we might call the ‘top end’, the criados of great nobles such as the House of Aguilar were often high-ranking individuals themselves acting on behalf of their masters and it is in these roles that we find the Baezas, collecting rents, witnessing official transactions and acting as their legal representatives.19 Converso families, such as the Baezas, acted as a buffer between the local nobility and the populace – the visible face of power, collecting taxes, managing finances and defending vested interests in their roles as members of the town council.20 The word ‘criado’ is usually rendered in English as ‘servant’, which could imply dependency, exclusivity and unidirectional power influence. In fact, the Baezas’ multifaceted relationship with their lords pulled in both directions and they were not simply followers but influencers too, especially during the minorities of their noble masters.

Hernando’s father Juan de Baeza seems to have held his position as mayordomo de los propios from the mid-1440s, while Gonzalo Rodríguez de Baeza was Town Clerk from even earlier and his son Fernán – who has sometimes been confused with my subject, his cousin Hernando – was a jurado (parish representative) from 1449 or earlier.21 These dates are significant because it was in 1449 that an infamous seminal attempt was made in Toledo to discriminate against new Christians by denying them access to public offices such as those held by the Baezas in Cordoba.22 Fourteen judeoconverso members of Toledo town council were excluded on the grounds that the religion of their ancestors made their allegiance suspect. The rationale for this was the supposed enmity of both Jews and Muslims towards Christian society and the allegation that Jews had been betraying the people of Toledo ever since the Muslim invasion (i.e., since the year 711). Although the decree was part of a wider political rebellion which was quickly quashed, it marked the first attempt to institutionalize long-standing anti-Jewish sentiment against the conversos, a move that, in the following century, was to become embedded throughout public life in Spain through limpieza de sangre statutes.23

In the same year of 1449, there were anti-converso riots in Guadalupe, site of a venerated image of the Virgin around which the Jeronymite Order had established its lead monastery. The Order had attracted a large number of former Jews and was in the vanguard of developing a new, inner spirituality which was not a retreat from the world but rather one which harmonized with astute management of worldly resources.24 Like Cordoba, where it seems there were also similar disturbances, there were a large number of conversos living in the village which had grown up around the monastery.25 It was these expressions of prejudice and violence which motivated Cartagena and Oropesa to develop their defence of converts within the Christian Church. Baeza would later reveal his own inclination towards the Jeronymite Order and write about the power of the Eucharist to unite the Christian forces fighting against the ‘Moors’, aligning himself with the new theology of these writers.26

The affinity with the Jeronymites expressed in Baeza’s text is supported by evidence that members of his family – and their noble masters – were already sympathetic towards the Order by the mid-fifteenth century. Fernán Rodríguez de Baeza, Hernando’s older cousin, had been a page to Pedro Fernández de Córdoba, Lord of Aguilar from 1441.27 In 1455, aged only 31, Don Pedro died, leaving Fernán two horses in a will made on his deathbed.28 The following year, Fernán made a donation of two mills to the local Jeronymite monastery of Valparaíso which adjoined his own family’s property just outside Cordoba, with a behest for the monks to pray for his master’s soul.29 The connection with the monastery spread over several generations: Hernando’s daughter, Teresa Álvarez, was buried there and his grandson, Captain Gaspar de Velasco, asked to be buried alongside her.30 Fernán’s 1456 donation was a public assertion of his Christian identity and, given the mid-century hardening of attitudes towards conversos, suggests that he may have started to feel under suspicion. Coinciding with the development of Alonso de Oropesa’s integrationist arguments concerning the rol...